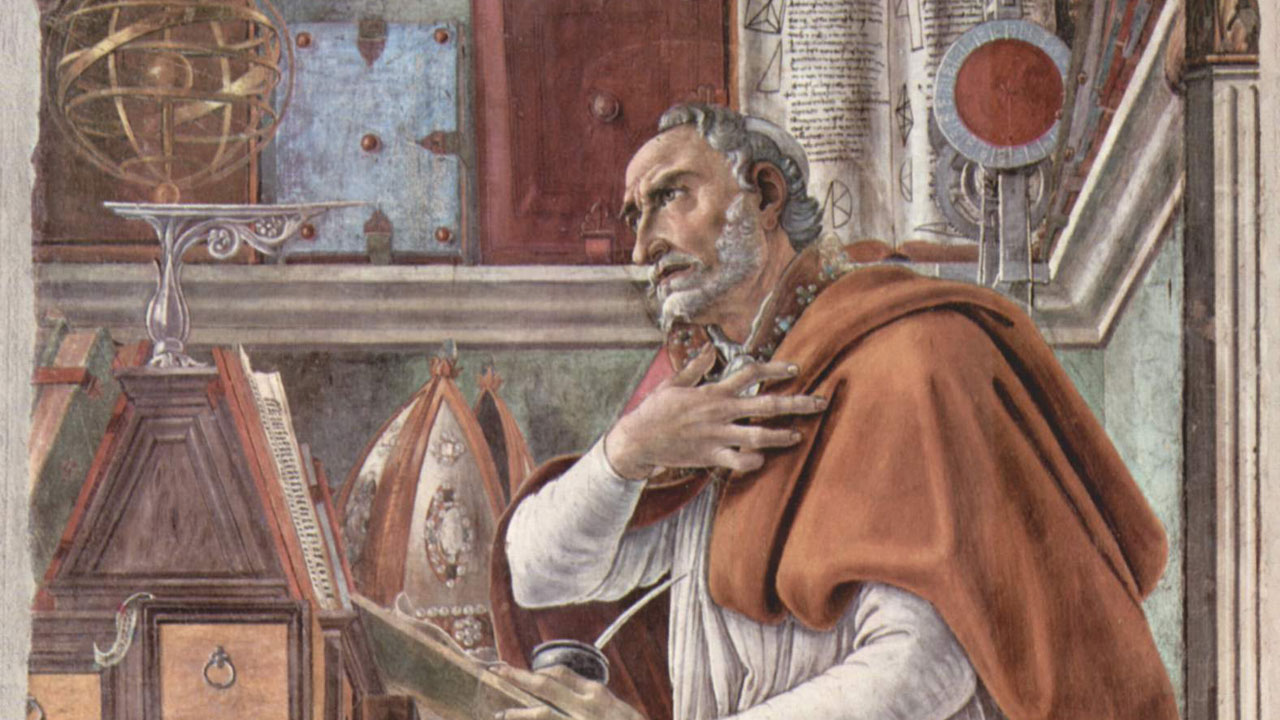

Augustine: A Giant Out of His Time

Reputed to be the first of the church fathers to have an Internet website devoted to his life and works, Augustine stands head and shoulders above all his peers.

He was born in 354 to a humble family in the hinterland of what is now Algeria, then a prosperous part of the Roman Empire. His parents sacrificed to provide their son with the educational opportunities of his day. He eventually rose to the rank of bishop within the Roman Catholic Church, but the contribution he made to the theology of that church ensured that all future generations of Roman Catholics would remember his name. Indeed, most of Christendom has felt his influence.

The son of a devout Catholic mother and a pagan father, Augustine was schooled in Madaura, close to his hometown, prior to being sent to Carthage at age 17 to enhance his education in rhetoric. There he indulged in the life of the city and, oblivious to the instruction of his mother, took a mistress who bore him a son when he was 18.

Contrary to custom, Augustine’s studies were principally in Latin rather than Greek. He informs us in his Confessions that Cicero’s Hortensius had a particularly great effect on him. He also writes that as a student he was driven by a thirst for wisdom, a love of the name of Christ, and a simultaneous rejection of Scripture.

His search for wisdom and truth brought him to the Manichee community. Manichaeism was a religion that seemed to have answers for most of the philosophical questions that the pagan world raised about the existence of evil—answers that, in Augustine’s view, the Catholic Church could not provide.

The pursuit of a career led the young man from Carthage back to his hometown of Thagaste, where to his mother’s disgust he convinced a prominent citizen to become a Manichee. A year later he was back in Carthage, where he matured as an eloquent orator and consummate scholar.

But he wanted more in life than Africa could provide, so at about the age of 30 he moved to Rome, the center of his universe. Through the good offices of Manichee friends, he was appointed to a post as professor of rhetoric at the Imperial Court in Milan.

His mother, now a widow, followed him to Milan, hoping to arrange a society marriage appropriate to his high-profile position. Augustine acquiesced and was betrothed to a girl who was not yet of marriageable age. His mistress of more than 10 years was dispatched back to Africa, while his son, Adeodatus, remained with him in Milan.

The need for connections in Milan brought Augustine in contact with Ambrose, who was one of the most celebrated bishops of his day and one of the most influential men in Milan. Ambrose’s eloquence and handling of the Scriptures in sermons aroused Augustine’s interest. The bishop presented his faith as a radically other-worldly Neoplatonic philosophy. In the words of biographer Peter Brown, “For Ambrose, the followers of Plato were the ‘aristocrats of thought.’” It was Augustine’s own attraction to Neoplatonic thought that, through Ambrose, eventually reconciled him to Roman Christianity.

It was Augustine’s attraction to Neoplatonic thought that eventually reconciled him to Roman Christianity.

Augustine’s associations with Manichaeism and the Neoplatonists were to shape the entirety of his future work, but as yet he was fighting an inner conflict: on the one hand, his impending marriage and accompanying ambitions, and on the other, his desire to dedicate himself to a search for truth and wisdom, a pursuit that in the tradition of many great philosophers was typically conducted in a celibate state.

About this time, a friend from North Africa visited Augustine and described the monastic life and the conquest of the self through meditation. At the end of the summer of 386, Augustine resolved with his friends and his mother to pursue a life of monasticism, and he informed Ambrose of his desire to be baptized, which was undertaken before the following Easter.

Between the expression of his desire for the monastic life and its reality, Augustine experienced the death of both his mother and his son. At 35 he returned to his hometown in Africa with a few friends to establish a monastery, which was in reality simply an extension of his former home—a place for philosophical reflection and debate rather than seclusion from society.

Two years later he visited the African coastal city of Hippo Regius, where, according to scholar James O’Donnell, Augustine “found himself virtually conscripted into the priesthood by the local congregation.” As a priest, Augustine devoted himself to the study of Scripture in a different way than before. He prepared himself for the years ahead—for struggles with heretics and for the copious amounts of writing that he would undertake. During this period he wrote the first of his treatises against the Manichees.

In 395 the bishop of Hippo died and Augustine was appointed in his place, a role he held until his own death. He now set himself to fight three great battles. The first was for the life of his community, in that paganism still threatened to engulf the church.

Second, he continued the effort to christianize the Roman world. Augustine was convinced that if that effort was to succeed, Christianity would have to provide the answers that the educated in society sought. In particular, it would have to answer the question of evil that had first attracted him to Manichaeism. Augustine’s City of God thus became an apologetic for the Christian world against the backdrop of a pagan society. Original sin, grace and predestination became the bishop’s rallying points in his attempt to create a theology that would address the question of evil.

Last, Augustine battled schismatics over aspects of the faith of the church. Whereas the Donatists were quickly dealt with, the Pelagianists occupied much of his ministry.

Augustine encouraged monasticism for both men and women, laymen and clerics. By the end of the fifth century, some 35 Augustinian monasteries were known in Africa, though the Order of St. Augustine wasn’t officially established until some 750 years later under Pope Innocent IV. Martin Luther was perhaps the best-known member of this monastic order.

In 430, the Vandals invaded Hippo and Augustine’s life came to an end. But his copious written works, aspects of which are foundational to both Roman Catholic and Protestant theology, ensured that his name would live on.