Another Jesus

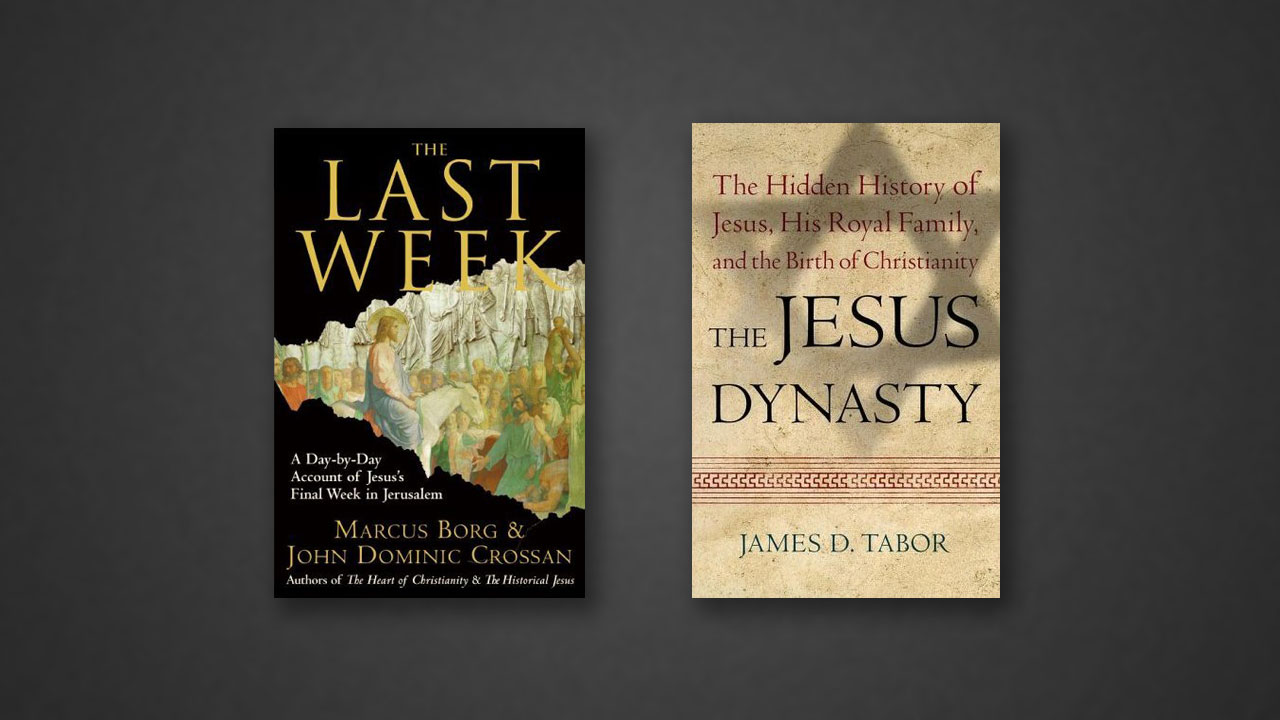

The Last Week: A Day-by-Day Account of Jesus’s Final Week in Jerusalem

Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan. 2006. Harper San Francisco, Harper Collins, New York. 220 pages.

The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity

James D. Tabor. 2006. Simon & Schuster, New York. 363 pages.

Each year around Passover and Easter we are assailed by new books, magazine articles and sometimes movies with religious themes. God is big business. In 2004 it was Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, with its focus on Jesus’ last 12 hours of intense suffering. This year two new books threw the spotlight on Jesus of Nazareth once more.

Reacting to Gibson, The Last Week promises to deliver a thorough day-by-day account of Jesus’ final days, not just hours. The jacket tells us that “two of today’s top Jesus experts [Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan] offer what they believe is the real gospel account of Jesus’s final week in Jerusalem.” Secondarily, because of problems they see with current church observance of Easter, Borg and Crossan seek to “supply a needed corrective and proper narrative basis both for sacred liturgy within the church and for story, play, and film inside or outside it.”

Religious historian James Tabor has a very different agenda: The Jesus Dynasty is the author’s personal summing up of more than 30 years of trying to discover the Jesus of history. His conclusions are controversial. As he put it in a message to several who have been close friends and associates through the years, “it is quite different from the position I once held as a young man before my decades of formal education and research. I have learned to not judge others by theological dogmas and formulations. I am much more interested in how one relates to the message of Jesus as a messianic proclaimer of the Kingdom of God on earth in his own time and context. It is that dynamic message, proclaimed by Jesus and echoed by the early Jerusalem church, set in its thoroughly Jewish context, with which I most identify. The person of Jesus is no longer as central to me as the message that Jesus proclaimed. My own sense is that with few exceptions it has been clouded by theological affirmations and confessions of who Jesus was, rather than what he taught and preached.”

Both books manage to illuminate and confuse.

No Good Friday?

Acknowledging the lack of appreciation of Jesus’ Jewish milieu for most of two millennia, Borg and Crossan write encouragingly that “much of the scholarship of the last half century, especially the last twenty years, has rightly emphasized that we must understand Jesus within Judaism, not against Judaism. Jesus was a part of Judaism, not apart from Judaism.” Together they lament the distortions of the past, adding that “after two thousand years of theological anti-Judaism and even racial anti-Semitism derived from this story, it is time to read it again and get it right, to follow it closely and understand fully its narrative logic.”

“After two thousand years of theological anti-Judaism and even racial anti-Semitism derived from this story, it is time to read it again and get it right, to follow it closely and understand fully its narrative logic.”

With these ambitious goals in place, we might expect to find a detailed explanation of the way the Jewish people kept the Passover festival, acknowledging the fact, essential to understanding, that the week of Jesus’ death encompassed two holy days: the annual Sabbath called “the first day of unleavened bread,” and the weekly seventh-day Sabbath (see John 19:31 and Matthew 28:1). But the authors provide no such information, and their account suffers accordingly.

They do say, “We do not in this book intend to attempt a historical reconstruction of Jesus’s last week on earth. Our purpose is not to distinguish what actually happened from the way it is recorded in the four gospels, which proclaim it as ‘good news’ (gospel).”

In other words, these Jesus experts do not believe that the Gospel accounts record what really happened. Nor do the authors intend in this book to tell us what they think happened. What, then, is their main purpose? It would seem to center on solidifying liturgical practice across the traditional Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday period. Concerned that “Holy Week” is being compressed by the substitution of “Passion Sunday” for “Palm Sunday,” they use Mark’s Gospel alone to appeal for eight days of careful observance.

The fact that Mark gives no indication that Sunday was the day when the crowds welcomed Jesus as a king as He entered the city, and that only one of the two Sabbaths of that week is mentioned by the authors, serves only to highlight the importance of their comment that “how this story is told matters greatly.” On that much we agree. It does matter how the story is told, especially if we are to understand the implications for us of Jesus’ example within Judaism. It has to be told accurately.

“We do not in this book intend to attempt a historical reconstruction of Jesus’s last week on earth. Our purpose is not to distinguish what actually happened from the way it is recorded in the four gospels. . . .”

The instruction in the Hebrew Scriptures regarding Passover specifies the date of Nisan 14 for its observance. On the Hebrew calendar the new day begins at sunset. The New Testament portrays Jesus symbolically as the Passover Lamb (see John 1:29, 35–36, 40–41; 1 Corinthians 5:7). Thus, His last Passover meal and death had to occur during Nisan 14, as demonstrated by a careful reading of the Gospels.

Which day was Nisan 14 in the year of Jesus’ death? Was it a Friday? As noted, an important clue arises in John 19:31, where the Gospel writer comments that Jesus’ body could not remain on the crucifixion stake after sunset, because “that Sabbath was a high day.” The new day that began at sunset following Jesus’ death was Nisan 15, the special annual Sabbath in the Hebrew calendar known as the first day of the Festival of Unleavened Bread (see Leviticus 23:6–7).

John also specifies that “six days before the Passover” Jesus came to Bethany outside Jerusalem (John 12:1), bringing us back to Nisan 8. Going to the other end of the Passover week and counting back from sunset at the beginning of the first day of the new week by the three days and three nights that Jesus had said he would be “in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40), we arrive at Wednesday sunset for His being placed in the tomb (Luke 23:53–54). Following the Gospel accounts forward from Nisan 8 (not backward from an assumed “Good Friday”), we can logically arrive at Saturday for Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on a donkey; at Tuesday evening for His Passover meal before His betrayal; and again at Wednesday afternoon for His death. That evening He was already in the tomb. Thursday was the special annual Sabbath and the day that guards were posted at the tomb (Matthew 27:62–66). Friday was the preparation day for the weekly Sabbath that began at sunset. Then, according to Matthew’s Gospel, “after the Sabbath, as the first day of the week began to dawn” (Matthew 28:1), the women came to Jesus’ tomb and found it empty. The reason, of course, was that Jesus had been resurrected about 12 hours earlier.

Getting Closer

Borg and Crossan are not alone in getting important details wrong, though some authors get a little closer to the facts. In The Jesus Dynasty, James Tabor unconventionally has Jesus crucified on a Thursday. Further, he conflates the Passover meal and the First Day of Unleavened Bread on Nisan 15. Undoubtedly he does this because the Jewish temple authorities in Jesus’ time killed Passover lambs late on the 14th—Wednesday afternoon by Roman reckoning—and like Jews today they celebrated the Passover at the beginning of the 15th. Commentators have often wondered whether Jesus’ last meal with the disciples was a Passover, as described in Matthew, Mark and Luke, or simply a meal the night before the Passover as John seems to portray. At that time, however, Jews did not have a single approach to the Passover as they do today. Some, like Jesus and His disciples, observed it at the beginning of the 14th according to the Torah—in this case on Tuesday evening. Others, such as the Pharisees, observed it at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th. This explains the apparent contradiction in the Gospel accounts between the actions of Jesus and His disciples and those of the Pharisees.

The basis for Jesus’ observance of the Passover in the evening at the beginning of the 14th is found in Exodus 12. There we read that the Israelites were to keep the lamb until the 14th and kill it at twilight (verse 6), and not go out till morning (verse 22). The following day they prepared to leave Egypt and left on the 15th (compare Exodus 13:3–4, 7, and Leviticus 23:6). They did not eat the Passover on the 15th. Jesus followed the original pattern in Exodus.

The difference between the two ways of observing the Passover produced the supreme irony that when Jesus died at three in the afternoon, the sacrifice of Passover lambs was being carried out at the temple. As the people carried their dead lambs home for roasting that evening, Jesus, the rejected dead Lamb of God, was being placed in the tomb.

A Known Alternative

Someone who paid close attention to the New Testament record was R.A. Torrey. He was a graduate of Yale Divinity School and successor to Dwight L. Moody at the Moody Bible Institute. Writing in 1907 about the chronology of crucifixion week, he said: “To sum it all up, Jesus died about sunset on Wednesday. Seventy-two hours later, exactly three days and three nights, at the beginning of the first day of the week (Saturday at sunset), He arose again from the grave. When the women visited the tomb just before dawn the next morning, they found the grave already empty. . . .

“There is absolutely nothing in favor of Friday crucifixion, but everything in the Scripture is perfectly harmonized by Wednesday crucifixion. It is remarkable how many prophetical and typical passages of the Old Testament are fulfilled and how many seeming discrepancies in the gospel narratives are straightened out when we once come to understand that Jesus died on Wednesday and not on Friday” (Difficulties in the Bible, 1907, 1964).

The English minister Leonard Pearson came to the same conclusions in 1939. He wrote: “Was Christ three days and three nights in the grave? Good Friday is the day usually kept to commemorate His precious death and burial, but if He was really buried on a Friday and arose on Sunday morning then at the longest His Body was not more than thirty-seven hours in the grave. The Bible nowhere says that Christ died on a Friday, but that He suffered as the true Passover and therefore on the 14th of the month Nisan. In the year of our Lord’s sacrifice the 14th of Nisan fell on a Wednesday. In the East time is reckoned from sunset to sunset. Sunset Wednesday to sunset Thursday—one day; sunset Thursday to sunset Friday—one day; sunset Friday to sunset Saturday—one day. So we get the full period of three days and three nights and early, before sun-rising, the tomb was empty and our Lord was risen. Hallelujah!

“In the Gospel story there is the mention of the Sabbath and this has been taken as the weekly Sabbath, whereas it is the Passover Sabbath. In other words, there are two Sabbaths in the Passover week” (Through the Land of Babylonia, 1939, 1951).

Perhaps Pearson was following the lead of Torrey or of E.W. Bullinger (descendant of the Swiss reformer Heinrich Bullinger), whose 1922 edition of the King James Bible, with extensive notes, explains the reasons for the difficulties encountered by many in accurately explaining the chronology of Jesus’ last week. Bullinger wrote that “the difficulties . . . have arisen (1) from not having noted [certain biblical] fixed points; (2) from the fact of Gentiles’ not having been conversant with the law concerning the three great feasts of the Lord; and (3) from not having reckoned the days as commencing (some six hours before our own) and running from sunset to sunset, instead of from midnight to midnight” (Companion Bible [1974 edition], Appendix 156).

When you compare the conclusions of Torrey, Pearson and Bullinger with many of today’s popular books, documentaries, movies and magazine articles about Jesus’ last week, it’s not difficult to see what is missing. These men were not overcome by doubt and skepticism.

History or His Story?

While James Tabor would like to see his book as a contribution to the debate on the “historical Jesus,” it really addresses a different issue. It is an attempt to recover what the author perceives as the original teaching of Christianity—a laudable undertaking and an enterprise Vision supports. But does Tabor achieve that goal?

The book is written for a general audience rather than for the author’s academic peers. He adopts a first-person approach to create a sense of dialogue with the reader as he takes us along on what is his own personal pilgrimage. In the process, Tabor challenges a number of ideas that are embedded in traditional Christianity. Often however, because he doesn’t examine every side of an issue as would be expected if he were writing to his peers, his style leaves the reader sensing that he holds a view personally rather than professionally.

In dealing with the historical Jesus, Tabor sets out his premises. We are frequently reminded that he is a historian who seeks to apply current methods of critical historiography to the New Testament accounts, including acceptance of the premise that the Gospels were not written by eyewitnesses or during the lifetime of the original disciples. But Tabor fails to consider the consequences of this approach. If the Gospels were written, as he claims, late in the first century by people who were not eyewitnesses, they are no more than secondary sources; consequently, how can he rely on them to establish any of his facts? Yet “as a historian” he has accepted them as valid historical accounts. Otherwise his whole thesis falls apart. This is most telling when we come to his treatment of Luke’s two works, the Gospel by his name and the book of Acts.

Miracles have no place in Tabor’s approach to history. Those in the religious community for whom the denial of miracles is heretical will therefore tend to dismiss this book out of hand, failing to appreciate some of the other material that Tabor brings to the discussion.

Of course, the denial of miracles is not new. The New Testament itself shows that the accounts of a virgin birth and a resurrection from the dead were subject to challenge and denial from the earliest time. Despite Tabor’s penchant to speculate about events relating to the time of Christ, he is ultimately constrained by his method: what can be proved, as opposed to what is a matter of theology, faith or dogma. In Tabor’s world, events either have to have a rational explanation or they didn’t occur. In other words, his approach leaves him dealing with human accounts rather than divine events.

Thus, when he tackles the matter of who Jesus’ father was, he can consider only human paternity. Although Tabor does not explicitly state that the Roman-Jewish soldier Pantera was the father of Jesus, his one-sided treatment of the old speculation, not to mention his failure to consider alternatives, calls into question his role as a serious historian. After all, it has also been postulated that the name “Pantera” could have originated as a derisive rejoinder to those who believed in the virgin birth. Pantera may be a play on the term virgin (Greek, pantheros). Hence the “son of a virgin” could cynically be reduced to “son of pantera.”

Paul Versus James

Tabor’s handling of material in the book of Acts relating to succession within the so-called Jesus movement is perhaps the weakest element in his presentation. But it is an issue that demands some attention. His idea that Luke promotes Paul at the expense of James seems as tenuous as the 19th-century Tubingen School’s speculative Peter-versus-Paul conflict. Given his dating of the Gospels, Tabor must accept that the book of Acts was written by Luke after the death of both Paul and James. So the idea of collusion between Luke and Paul is immediately suspect.

And if James was so antithetical to Paul, why would either Paul or Luke have referred to him at all? Luke could easily have “airbrushed” opponents out of the picture. Or he could simply have given James the same literary attention as he gave the majority of the apostles in the book of Acts: absolutely none. Instead, he records James as occupying a prominent role in the Jerusalem church and chairing the decisive Jerusalem Conference (Acts 15), which Paul attends. Paul himself writes about James being one of the pillars of the Church (Galatians 2:9). Certainly we would like to know more about James than we are told, but that could be said of almost every biblical character, including Jesus. The frequency with which Tabor resorts to speculation about historical issues relating to Jesus indicates how few extrabiblical facts we have about the central figure.

Apropos of a supposed Pauline supremacy, it is important to consider the arrangement of the books of the New Testament. The privileging of the writings of Paul over the other apostolic epistles was adopted by Jerome in compiling the Vulgate in the fourth century. It not only gave Rome the ascendancy it desired over things Jewish, but it provided what was probably viewed as a fitting continuation to the book of Acts, which ended in Rome. Jerome was not alone in making the decision to structure the Vulgate the way he did. It had been a matter of debate beforehand, but not on the part of Paul or Luke. If, as the Syriac and some of the Greek texts and early witnesses suggest, the book of James and the other general epistles (Peter, John and Jude) followed the book of Acts, then Tabor’s argument about Pauline privilege fails. The early Church did not see the relationship between James and Paul as contradictory or competitive.

In reality, Tabor’s thesis depends not on Luke and Paul but rather on the actions of protagonists later in history who wished to minimize the “Jewishness” of the New Testament. In terms of subsequent church history, perhaps Tabor needs to consider Peter’s warning that some people in his time twisted Paul’s writings to their own destruction (2 Peter 3:15–16).

Useful Focal Points

It is always a challenge, in a book that covers such a long period and numerous disciplines within New Testament studies and history, to maintain a consistent level of scholarship. As a result, areas of specialty stand out. Archaeology is James Tabor’s real interest. Accordingly, he introduces us to some of the current discoveries that pertain to the New Testament and provides a useful focus and fleshing out of the history that he seeks to relate. In this he is to be applauded.

He is also not averse to contradicting centuries of popular conceptions about the time of Jesus that are based more on myth than reality. For example, in the map section—very conveniently placed at the start of the book—he lists an “alternative Golgotha” to the east of Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives. The artwork of the crucifixion, found inside the back cover, portrays this perspective. Such a revolutionary approach deserves more attention on his part than the two pages it receives, especially if archaeological evidence exists to support the depiction.

As already noted with respect to Jesus’ final Passover, Tabor dates it in 30 C.E. rather than the traditional 33. The discussion is important, as it introduces what we have shown earlier—the fact of there having been two Sabbaths in the crucifixion week, an element that is so easily overlooked. But how does he arrive at a Thursday evening through Friday sunset for Nisan 15? Tabor makes general reference to tables and computer programs in his endnotes, but which computer program did he use, or which tables did he consult? Having checked several of both, we can’t find one that puts Nisan 15 on a Thursday in the year 30. This is one of the shortcomings of the book. Although it is endowed with endnotes to reference sources, frequently the notes are either incomplete or lacking in the areas of greatest interest.

Bread-and-Butter Issues

Careful exegesis of the New Testament does not appear to be of the same interest to Tabor as archaeology. It’s not that he doesn’t know Hebrew and Greek. He does and is very proficient in both languages, but that doesn’t mean that he reads as carefully as he should or asks the right questions of the text.

For instance, he discusses the bread that Jesus had at His last meal with the 12 disciples. Because the Greek term artos is used at what he calls Jesus’ last supper, Tabor states that it was a normal loaf of bread and hence the meal could not have been the Passover, which required unleavened bread. Yet artos is used for bread in a very general way in the New Testament. If bread is unleavened, that fact is made clear either by the use of the adjective azuma or from the context. New Testament references to the consecrated bread that was kept in the temple at Jerusalem use the word artos, and we know from the Torah that it was unleavened. Likewise the manna that Israel received in the wilderness, though made with neither grain nor yeast, was called artos, or bread. So care is needed in coming to a conclusion about the bread Jesus used that evening.

Consider also the context of the supper that Jesus had. In the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke), the meal is placed during the time of unleavened bread. In making preparations for the meal, the writers tell us that the period had already begun (Mark 14:12–17; Matthew 26:17–20; Luke 22:7–14). Bakers stopped preparing regular bread before the Passover so that they had a stock of unleavened bread for those visiting Jerusalem for the festival.

Interestingly, Paul refers to the bread and the wine of that meal in 1 Corinthians 10:16–17, describing the cup of wine as “the cup of blessing,”—the same title applied to one of the cups of wine used at the Jewish Passover meal to this day. If Paul is talking about the same cup that is used at the Passover, then the context would demand that the artos be unleavened. And contra Tabor, Paul would have seen the meal Jesus had with His disciples as a Passover meal, and the Church event which he describes to the Corinthians as a Passover celebration. Perhaps if Paul were not such a problem for Tabor, these thoughts would rise to the surface more readily.

Tabor does succeed in one other area. Inadvertently, he restores life to an early movement known to us from the history of the first three centuries after Christ as the Ebionites. They accepted Jesus’ messianic status and remained law observant, but they rejected claims of His resurrection and divinity. Perhaps Professor Tabor should be classified as a neo-Ebionite.

Getting the Story Right

As a society we love simple answers to the questions we face. Tabor’s easy answer of dynastic succession as the cause for the difference between the “Christianity” of Jesus and that which is common today doesn’t hold water. In fact, all attempts to explain the differences by using New Testament writers, no matter how cogent the arguments appear, will ultimately fail. That’s because the answers lie in the politics of church and state within the Roman Empire, not in the New Testament.

Similarly, Borg and Crossan, because they reject the Bible itself as a credible basis of fact regarding Jesus’ death and resurrection, go astray in their conclusions. Men like Bullinger, Pearson and Torrey, on the other hand, simply took the Bible at its word and tried to reflect accurately the details of its accounts in their Jewish milieu. Their comments are well worth considering in getting the story and its implications right.