Productive in Prison

The book of Acts closes with Paul imprisoned for two years in Rome (Acts 28:30). There he awaited his audience with the emperor Nero, to whom he had appealed against the charges brought by his religious enemies in Jerusalem.

It is no doubt significant that the Jewish leaders in the capital had heard nothing about him from Judea, nor had anyone spoken evil of him to them. It was, after all, a trumped-up charge that had seen no resolution over several years. On the other hand, the Jewish leaders in Rome had heard of the “sect” to which Paul belonged. It was “spoken against” everywhere, they said, and they solicited his opinion about it (verses 21–22). But when Paul explained, the result was a dispute, followed by rejection. Recalling a prophecy of Isaiah that “this people . . . will indeed hear but never understand” (verses 26–27), Paul announced that he would concentrate on giving out his message to non-Jewish peoples. He also no doubt continued to meet his fellow Church of God brethren, who had come out to meet him as he approached Rome on the Appian Way (verses 13–15).

During those two years in prison, the Roman authorities allowed Paul considerable freedom to pursue his calling. He was able to welcome “all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance” (verses 30–31).

This is an interesting division of responsibilities and provides food for thought. Paul had a twofold role: he was entrusted with both a public and a private work. His public work was that of preaching about, or announcing or proclaiming (in Greek, kerusso), the coming of the kingdom of God on the earth. It was the same work that Jesus had done in His public role (see Mark 1:14). By contrast, the Greek word for teaching or instructing is didasko. This was the second aspect of both Jesus’ and Paul’s role. They taught a way of life to those who believed the announcement about the kingdom of God to prepare them for its establishment on the earth.

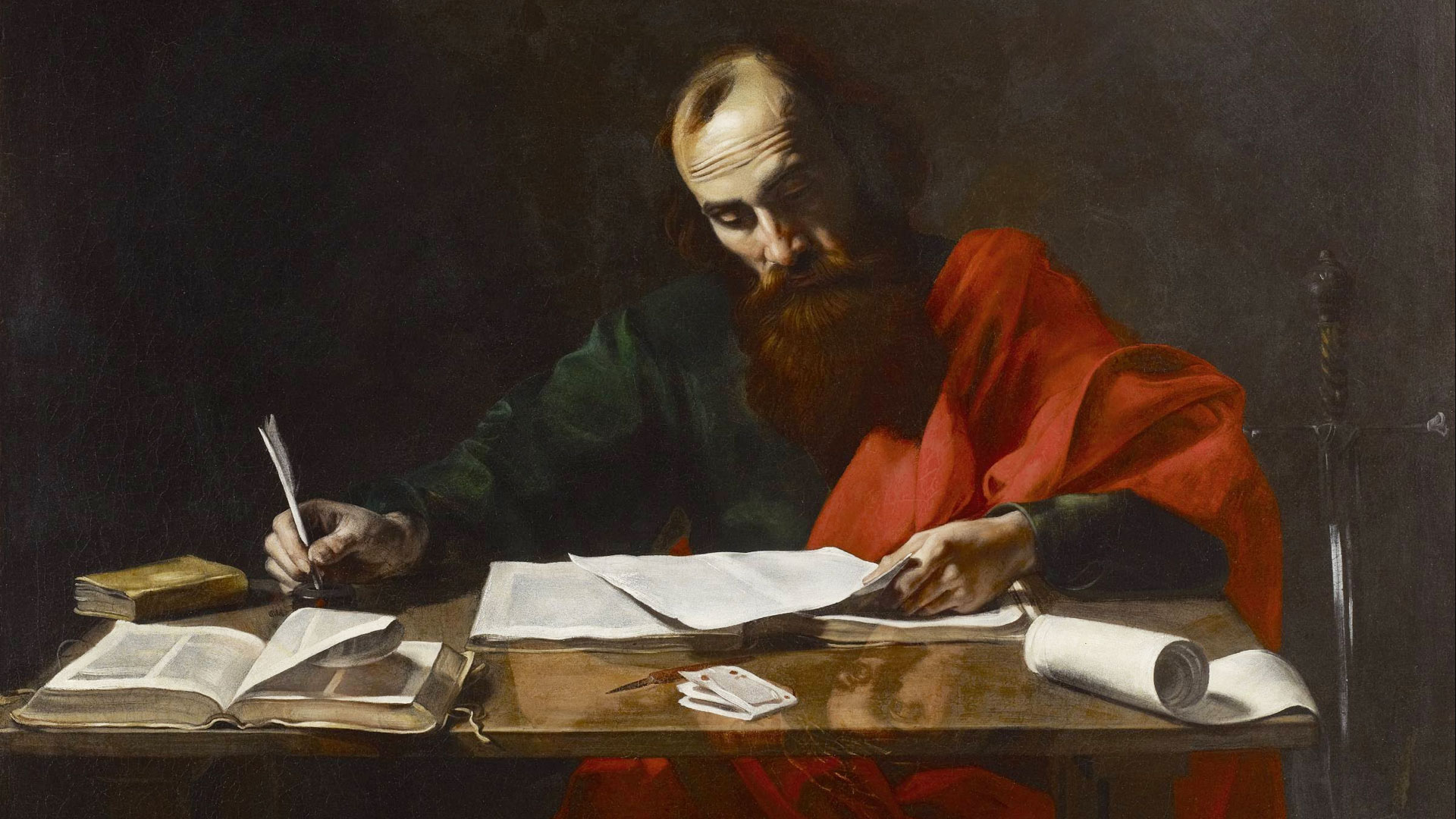

Letters From Prison

During his time in Rome, Paul wrote several instructional letters that give an insight into both his pastoral care of the churches and his attention to a matter at the individual level.

He wrote to a wealthy Church member and friend named Philemon (Philemon 1), and also to congregations in three cities: Colossae, Ephesus and Philippi (see Colossians 4:3, 18; Ephesians 3:1; 4:1; 6:18–20; and Philippians 1:7, 12–17).

What can we learn from this correspondence?

Paul introduced himself to Philemon as “a prisoner for Christ Jesus” and well on in years (Philemon 1, 8–9) before asking for his indulgence in resolving a problem with one of his runaway slaves. The wrinkle in the situation was that the slave, Onesimus, had become a convert through Paul’s prison ministry (verse 10) and was now returning with Paul’s letter in hand (verse 12). Though the apostle could have used his authority to persuade Philemon to forgive his slave-become-brother and take him back, he rather entreated his friend, offering to cover any out-of-pocket costs or debts incurred by Onesimus (verses 18–19). Since the slave is mentioned as known to the church in Colossae—“who is one of you” (Colossians 4:9)—it is likely that Philemon also lived there.

Companions in Rome

As he signed off, Paul recorded for Philemon the names of several helpers, indicating that this imprisonment was not solitary. They include Epaphras, Mark, Aristarchus, Demas and Luke (verses 23–24). In his introduction, Paul had also mentioned Timothy, his spiritual son in the faith (see also Philippians 2:19, 22).

Epaphras was a tireless minister in the Colossian area, which also included congregations at nearby Laodicea and Hierapolis (Colossians 4:12–13). He had arrived in Rome bringing news of the state of the congregation at Colossae (Colossians 1:3–8). This caused Paul to compose a letter to them, which was carried back not by Epaphras, who stayed with Paul in Rome as his “fellow prisoner” (Philemon 23), but by Tychicus, “a beloved brother and faithful minister and fellow servant in the Lord,” and the slave Onesimus (Colossians 4:7–9). Tychicus had traveled with Paul from Greece to Jerusalem and was possibly an Ephesian (Acts 20:4). Perhaps this is the reason that Paul also entrusted him (Ephesians 6:21–22) with what is known to us as his letter to the Ephesians, though originally it may have been a circular letter destined for the churches in the Roman province of Asia (western Turkey) that were centered around the capital city (early manuscripts do not contain the words “in Ephesus” [Ephesians 1:1], and its content is more general).

Mark was likely John Mark, who had separated from Paul and Barnabas about 12 years earlier (see Colossians 4:10, where he is described as “the cousin of Barnabas”; see also Parts 3, 4 and 5 of The Apostles). This was an encouraging development in itself, and Paul later wrote to Timothy that “Mark . . . is very useful to me for ministry” (2 Timothy 4:11). An early tradition holds that Mark wrote the Gospel by his name for the Romans. Being present in Rome with Paul gives some support for that belief.

Aristarchus was a Thessalonian convert who had accompanied Paul on various other journeys (see Acts 19:29; 20:4), as well as on the voyage to Rome. Paul mentioned him also as “my fellow prisoner” in Rome (Colossians 4:10).

Demas, later described as “in love with this present world,” eventually deserted Paul (2 Timothy 4:10), whereas Luke, “the beloved physician” (Colossians 4:14) and author of both the Gospel by his name and the book of Acts, remained faithful to the end. He traveled with Paul to Rome on this occasion and also for his second and final imprisonment there.

In Colossians, Paul commends another helper, the Jewish convert Jesus (Justus), who was also close to him in his imprisonment.

Sometime during his stay in Rome, Paul was visited by Epaphroditus from Philippi. This resulted in the letter known to us as Philippians. Paul commended his visitor for his extraordinary assistance, “for he nearly died for the work of Christ, risking his life to complete what was lacking in your service to me” (Philippians 2:30). Once recovered, Epaphroditus returned to his home congregation with Paul’s letter (verse 25).

Thus we know that Paul was not alone in Rome in such difficult circumstances but was surrounded by several faithful and true brothers, not to mention the Church members who were residents of Rome (see Romans 16).

Success Under Duress

Despite the limitations on his freedom, Paul was intent on finding ways to continue the work of proclaiming the good news about God’s coming kingdom and the role Jesus had played in making reconciliation with the Father possible. He asked the members in Colossae and Ephesus to “pray also for us, that God may open to us a door for the word, to [boldly] declare the mystery of Christ, on account of which I am in prison” (Colossians 4:3; see also Ephesians 6:19). He also mentioned to the Philippians that “it has become known throughout the whole imperial guard and to all the rest that my imprisonment is for Christ” (Philippians 1:13–14). Paul was likely chained to various guards day and night in rotation (see Ephesians 6:20 and Acts 28:20, which mention a chain, or manacles); thus his every word would have been overheard.

And it was not only among the imperial guard that Paul’s message became known. At the close of his letter to the congregation at Philippi, he wrote, “All the saints greet you, especially those of Caesar’s household” (Philippians 4:22). Were these newly converted people Nero’s servants or relatives? Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing.

“All the saints greet you, but especially those who are of Caesar’s household.”

Paul fully expected that he would be released from his imprisonment. Hence his comment to Philemon, “Prepare a guest room for me” (Philemon 22), and to the Philippians, “I trust in the Lord that shortly I myself will come also” (Philippians 2:24).

Overlapping Messages

In the three congregational letters, Paul covered several overlapping themes. In Ephesians and Colossians, there is the reminder that it is only by special revelation from God that the Church understands what it does of His great purpose in creating humanity and sending Jesus Christ. Paul referred to this as a mystery (in Greek, musterion). The word signifies a secret, a hidden truth that is God’s alone to reveal if and when He chooses and to whomever He chooses. Paul emphasized that God had called certain individuals from the gentile world, as well as the Jewish world, to participate in a relationship with Him through Jesus Christ. This development had been hidden until the first century, when God chose to reveal it. It was, as Paul said, “the mystery hidden for ages and generations but now revealed to his saints” (Colossians 1:26), “which was not made known to the sons of men . . . as it has now been revealed to his holy apostles and prophets by the Spirit” (Ephesians 3:5). It was Paul’s specific responsibility to let this be known to those whom God had called in the gentile world, and as a result he was now a prisoner (Ephesians 3:1).

All three letters make reference to the need for boldness in proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God and Jesus Christ. As we have seen, Paul asked that the members in Colossae pray for him to be able to speak his message plainly and openly (Colossians 4:3). Similarly, he asked those to whom the Ephesian letter went for prayers that he would speak out boldly (Ephesians 6:19–20). He commended the members in Rome for doing just that themselves as a result of his imprisonment (Philippians 1:14) and expressed his hope that he, too, would act with boldness in answer to their prayers for him (verses 19–20).

Further, Paul was joyful in his suffering, because he knew that it had a great purpose not only for himself but also for the membership (Colossians 1:24; Ephesians 3:13). He did not want them to be discouraged by his situation, because he believed that it would all turn out for the good (Philippians 1:19).

Ephesians, Colossians and Philemon contain general instruction for the God-fearing family and for masters and slaves (Ephesians 5:22–6:9; Colossians 3:18–4:1; Philemon 10–18). Husbands and wives and children are encouraged to treat each other with mutual respect (Paul demonstrates in his letters to the Ephesians and the Colossians that he was far from the woman-hater that many have painted him to be). Converted masters are to treat slaves with fairness, and converted slaves are to work honorably.

Specific Messages

While there are overlaps in the letters, when it comes to the specific reasons for each letter, there are also differences. As we have seen already, Paul responded to the circumstances that were presented to him in respect of the congregations in Colossae and Philippi.

Judging by Paul’s letter to the Colossians, Epaphras had come with some serious concerns about their spiritual well-being. It seems that the brethren were being swayed by Greek philosophical ideas (Colossians 2:8). One of the central precepts concerned spirits who were said to rule the world and mediate between humans and God. According to this philosophy, such beings deserved worship, which included ascetic practices (Colossians 2:18). Paul sought to free the Colossians from this error by reminding them that followers of Jesus had no need for such human beliefs and practices. He wrote, “If with Christ you died to the elemental spirits of the world, why, as if you were still alive in the world, do you submit to regulations—‘Do not handle, Do not taste, Do not touch’ (referring to things that all perish as they are used)—according to human precepts and teachings?” (Colossians 2:20–22). This, he insisted, is “self-made religion” (verse 23) that might look appealing but is in fact an “empty deceit” (verse 8).

“Do nothing from selfishness or empty conceit, but with humility of mind regard one another as more important than yourselves; do not merely look out for your own personal interests, but also for the interests of others.”

Philippians was written in response to Epaphroditus visiting Paul in prison and bringing news of the congregation. It is a letter filled with gratitude on Paul’s part for the brethren’s spiritual development. He took the opportunity to teach them about the mind and attitude of Christ, which they should emulate. It is a humble mind that does nothing from motives of rivalry or conceit and seeks the good of others, willing to lay down life itself for them (Philippians 2:1–8). As followers of Jesus Christ, the Philippians were to live honorably on earth as citizens of the kingdom of heaven yet to come (Philippians 1:27).

As already mentioned, the letter we know as Ephesians was possibly meant for circulation in the region around the city, including places such as Laodicea, Hierapolis and Colossae, where Paul mentioned that church congregations existed and letters were exchanged (Colossians 4:13, 16). It is a more general letter than either Colossians or Philippians and deals with expansive themes in God’s plan. It explains the centrality of Jesus Christ’s life, death and resurrection to that plan (chapter 1) and includes His calling some to conversion in this life, ahead of others (chapters 2–3). It teaches the vital importance of unity among the believers and how they are educated and protected in God’s way (chapters 4–6).

Thus we see that Paul’s two-year house arrest in Rome was not spent idly, nor did the congregations in his care suffer from lack of attention from the aged apostle. And there is yet more to report.

Next time, Paul’s travels between his first and second Roman imprisonment.