A Future and a Hope

According to the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, Jews returned to Israel from Babylon and Persia once the prophesied 70 years as a captive people had come to an end. Their success would depend not just on rebuilding Jerusalem but on restoring a spiritually healthy community.

The section of the Hebrew Scriptures known as the Writings includes a unified two-part history of Judah’s return to the land of their ancestors. Originally presented as a single book, Ezra-Nehemiah dates from the Persian period (539–331, BCE throughout). Ezra tells the story of two returns, and Nehemiah recounts a third. Between the first two returns, events recorded in the book of Esther—the Jewish wife of the Persian monarch Xerxes (Ahasuerus)—unfolded.

Scholars debate the date of the completed manuscripts of Ezra and Nehemiah, but a two-stage process concluding somewhere between 400 and 300 seems reasonable. The overall structure of the combined books is

- a narrator’s account of the history prior to Ezra’s return (Ezra 1–6);

- Ezra’s memoir (Ezra 7–10);

- Nehemiah’s memoir (Nehemiah 1–13).

In this installment, we’ll focus on the account in Ezra. The book opens with the Babylonian era coming to an end and Cyrus, king of Persia (560/559–530), issuing his 538 proclamation to free those Jews who wished to return to Judah and to rebuild Jerusalem’s ruined temple (Ezra 1:1–3). The Cyrus cylinder, a clay cuneiform document discovered in the ruins of ancient Babylon in 1879, confirms that when expedient, the king adopted a policy favorable to captive peoples, sending them home with their confiscated religious objects (see verses 7–11).

Not every captive in Babylon wanted to return, suggesting that God stirred up the spirit of some but not others. Those who stayed behind in Babylon were asked to support those who did return by contributing precious items, goods and offerings. Other non-Israelite neighbors also helped with donations and “strengthened their hands” (verses 4–6).

The reference to divine involvement is an early indication of the thrust of these historic books: establishing a renewed community under God’s inspiration, guidance and blessing. As we’ll see, there is both a theocratic and a prophetic purpose underlying this narrative. The reference to Babylonians helping the freed exiles with gifts parallels the circumstances of the Israelites as they left slavery in Egypt (see Exodus 12:35–36). Cyrus’s permission to return to Jerusalem thus depicted a kind of second exodus from slavery to achieve freedom in the same land.

The First Return

The first six chapters of Ezra cover the period from the date of the decree (538) to the completion of the rebuilt temple in Jerusalem (516/515).

In chapter 1 we learn that the returnees represented three classes of society—priests, Levites and laity—from the three southern Israelite tribes of Judah, Benjamin and Levi (verse 5). In Ezra-Nehemiah, members of these tribes are viewed as the only true community, though other tribes were also present among them; note the mention of “all [the rest of] Israel” in Ezra 2:70. Initially they were led by Sheshbazzar, prince (or leader) of Judah, and Zerubbabel, of the line of David and later governor (1:8; 2:2; 6:7).

“The aim is to show that those returning were representative of Israel in its full extent (twelve tribes) and thus perhaps to provide an echo of the first Exodus.”

Chapter 2 details the origins of the returnees. First came the laity, listed by family name or domicile (verses 3–35); next four priestly families (36–39); then Levites, singers, gatekeepers, temple servants and those with unverifiable genealogies from places probably in Babylonia (verses 40–63). This list of 42,360 is likely a compilation made over time. Added to this were 7,337 servants and 200 singers, for a grand total of about 50,000 (verses 64–65).

In the third chapter we read about the beginning of worship at the temple site under the leadership of the chief priest, Joshua, and the governor, Zerubbabel. Together with their helpers, they first built the altar of burnt offerings. The account calls on the examples of both Moses and David, and through verbal parallels it evokes the memory of the construction of Solomon’s temple (compare verses 10–11 and 2 Chronicles 5:11; 7:6).

The writer also mentions the annual holy days, with a focus on the feasts of the seventh month. This establishes the revived community as one that was now faithful to the God of Israel, a repentant people who in captivity had learned their lesson.

To begin the rebuilding of the temple, they sought materials in Lebanon, paralleling the procuring of materials for the original temple built by Solomon (Ezra 3:7; 1 Chronicles 22:2–4; 2 Chronicles 2:7–15).

In the second year after returning, the leaders appointed Levites to oversee the project under the supervision of the priests. With a ceremony organized according to the instructions of King David, they laid the foundation (Ezra 3:8–11; 1 Chronicles 16:7–8, 34, 37). While many were joyful at this new beginning, many of the older priests, Levites and leaders, who remembered the original temple, expressed disappointment (Ezra 3:12). Perhaps their memories of Solomon’s temple were vivid enough to make the outline of the present foundation and the proposed materials seem uninspiring, as they had hoped for a recreation of the temple’s former splendor. The postexilic prophet Haggai noted the level of disappointment and offered God’s encouragement to Zerubbabel, Joshua and the people to continue the work (Haggai 2:2–9).

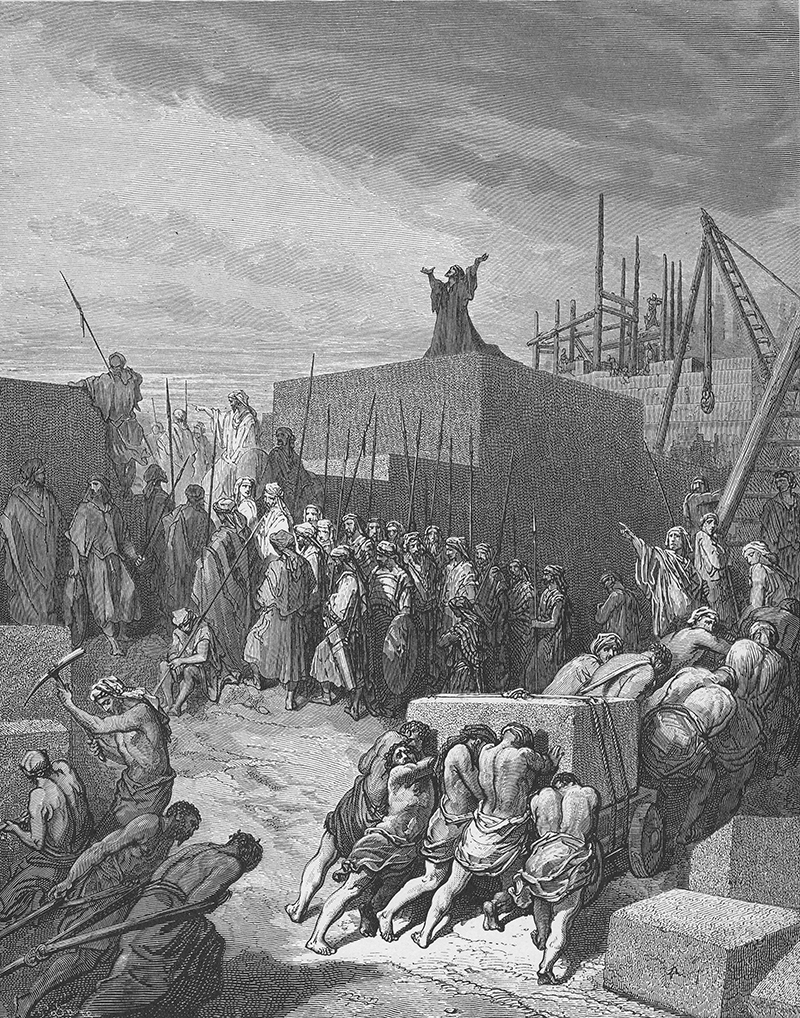

The Rebuilding of the Temple Is Begun by Gustave Doré, engraving (1866)

Opposing Forces

It wasn’t long before the reconstruction brought enemies to the fore. Local inhabitants, descended from non-Israelites brought in well over a hundred years earlier by the Assyrians to replace the exiled northern tribes, began a campaign of interference to obstruct the project. At first they cunningly offered to help with the work, claiming to worship the same god. The Jews rebuffed them, referencing the sole right to build that Cyrus had conferred on them. As a result, the adversaries frustrated the reconstruction work for several years, hiring people to speak against the project. So discouraged were the returnees that they made little real progress throughout the reigns of Cyrus and his son Cambyses (530–522). It was only in 520, in the days of the latter’s successor, Darius (522–486), that work recommenced (Ezra 4:1–5).

An inset section follows, covering the later reigns of Darius’s son and grandson, the Persian rulers Xerxes (486–465) and Artaxerxes I (465–424). It shows that that harassment by enemies continued for many years even after the temple was eventually completed. It was also during the reign of Xerxes that his queen, Esther, and her fellow Jews survived an attempt to destroy them empire-wide. During the second part of this period, with the temple rebuilt and Artaxerxes as ruler, Nehemiah engaged in rebuilding the Jerusalem wall, only to be hindered again by local enemies (verses 6–23).

The original narrative picks up in verse 24 with the comment that the construction work was on hold until the second year of Darius’s reign. Then, urged on by the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, Zerubbabel and Joshua recommenced building (Haggai 1:1–2; Zechariah 1:1, 16–17; Ezra 5:1–2).

Another attempt to hinder the construction originated with the governor of the region known as “Beyond the River.” He wrote a letter to Darius complaining about the Jews’ temple- and wall-building activities and asking that a search be made in the archives to verify their claim that Cyrus had authorized the work by a decree (verses 6–17). Darius confirmed the existence of the proclamation and instructed that work be held up no longer (6:1–12).

With the completion of the temple in the sixth year of Darius (516/515), a great celebration followed. Again the Jews paid attention to those elements that confirmed their identity as God’s renewed people: “the children of Israel, the priests and the Levites and the rest of the descendants of the captivity” came together to offer sacrifices at the dedication of the house of God. They also gave “as a sin offering for all Israel twelve male goats, according to the number of the tribes of Israel.” Going forward, they held to the instructions in “the Book of Moses” for the organization and work of the priests and Levites. Accordingly, they then observed the Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread and included those “who had separated themselves from the [ritual uncleanness] of the [peoples] of the land” (verses 13–21).

Ezra and the Second Return

Chapter 7 begins the memoir of Ezra, a priest and scribe, an expert in the law, and a direct descendant of Aaron, brother of Moses. Eighty years had passed since Cyrus proclaimed the Jews’ freedom from captivity, and Artaxerxes I now sent Ezra to Jerusalem to see that the law of God was being kept. Armed with a supporting letter from the king, Ezra prepared to set out from Babylon in 458, the seventh year of Artaxerxes’ reign, determined to teach God’s commandments to Israel (7:1–11).

“Ezra . . . concentrated his whole life on the study of the law. But it is not only a question of study—he also practiced the law. It was not a dead letter, but a living reality to him.”

The Persians, keen to seek the blessings of the gods of lands they conquered, provided Ezra with silver and gold, gifts and funding for sacrificial animals for the temple in Jerusalem. Ezra gathered a group of leading men, priests, Levites, servants and their families and left Babylon. After pausing a few days to fast for God’s protection, they continued the four-month journey to the land of Israel (chapter 8).

Chapter 9 tells us that the new returnees hadn’t been back in the land long before they recognized the poor example of the existing leadership in Jerusalem. They, and thus the people, had slipped back into old ways by intermarrying with their pagan neighbors. This greatly distressed Ezra. Having fasted once more, he approached God in repentant prayer on behalf of all his people. He knew that their forefathers had gone into captivity for such failure, and now, despite God’s deliverance from the Babylonians and favor from the Persians, they were breaking their covenant once more. But he also knew that they were in a period of grace, where they could experience spiritual revival though still under Persian subjection.

Ezra, moved by the people’s response when they saw him praying before the temple, and encouraged by one leader to take action, called an assembly of all the men in Judah three days hence (10:1–8). The result was agreement to separate from their pagan wives. The intermarriage problem was widespread, and it took some time and wise judgment to resolve each case individually (verses 10–17).

Ezra’s memoir concludes with a listing of all who had failed in this regard and had repented, the implication being that they were ready to distance themselves from the pagan ways of the local peoples and to be taught from God’s law. That Ezra did so is related in the next book, the account of Nehemiah, who would likewise return from Babylon during the reign of Artaxerxes and would serve as governor.