Mary, Mary? Quite the Contrary!

Mary Magdalene has been repainted to conform to modern agendas. But is her new image a truer likeness than the old?

Mary Magdalene, ex-prostitute and role model for fallen women, is most definitely “out.” “In” is a reinvented Magdalene, cobbled together according to your personal preferences: wife (or mistress) of Christ; mother of His child; apostle to the apostles; high priestess of an Egyptian religion; and/or spiritual and intellectual superior to Christ’s male disciples. However you view her, it’s clear that Mary Magdalene has lately been given a drastic makeover. And largely responsible for her new personae are a number of feminist theological scholars and writers.

Until recently, the basis of what people thought they knew about Magdalene came from some questionable Christian traditions, and to a lesser extent from the four New Testament Gospels. All but one scriptural reference mentions Mary in the context of events surrounding the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ. She was the first to witness the resurrected Christ, and she conveyed His instructions to the disciples. But she quickly fades from view in the remaining verses of the Gospels and in fact is never mentioned in subsequent Church history recorded in the book of Acts or the Epistles.

A number of noncanonical writings, however, claim to record dialogues between Mary and the risen Christ, or between her and the apostles. Among these Gnostic works, the so-called Gospel of Mary is key, though the Gospel of Philip is also widely cited, as is a document known as Pistis Sophia (Faith Wisdom). All portray a Mary in a different role than the one outlined in the four biblical Gospels.

Little was known of these extrabiblical writings until just before the 20th century. In 1896, a German Egyptologist bought a codex in Cairo that contained, among other things, a portion of the Gospel of Mary. Fragments of the Gospel of Mary were also found among the papyri later recovered at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt. Then in 1945, in a manner not unlike the discovery of the more famous and far more numerous Dead Sea Scrolls three years later, a copy of the Gospel of Philip along with other Gnostic texts was found in a sealed jar near the Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi. Modern-language translations began to be published in the late 1970s.

In the subsequent decades, the study of Mary Magdalene has understandably been stimulated and given new context by the contents of these additional Gnostic texts.

Thoroughly Modern Mary

The endeavor to “restore” Magdalene to what some believe is her rightful role has, to simplify it somewhat, been threefold.

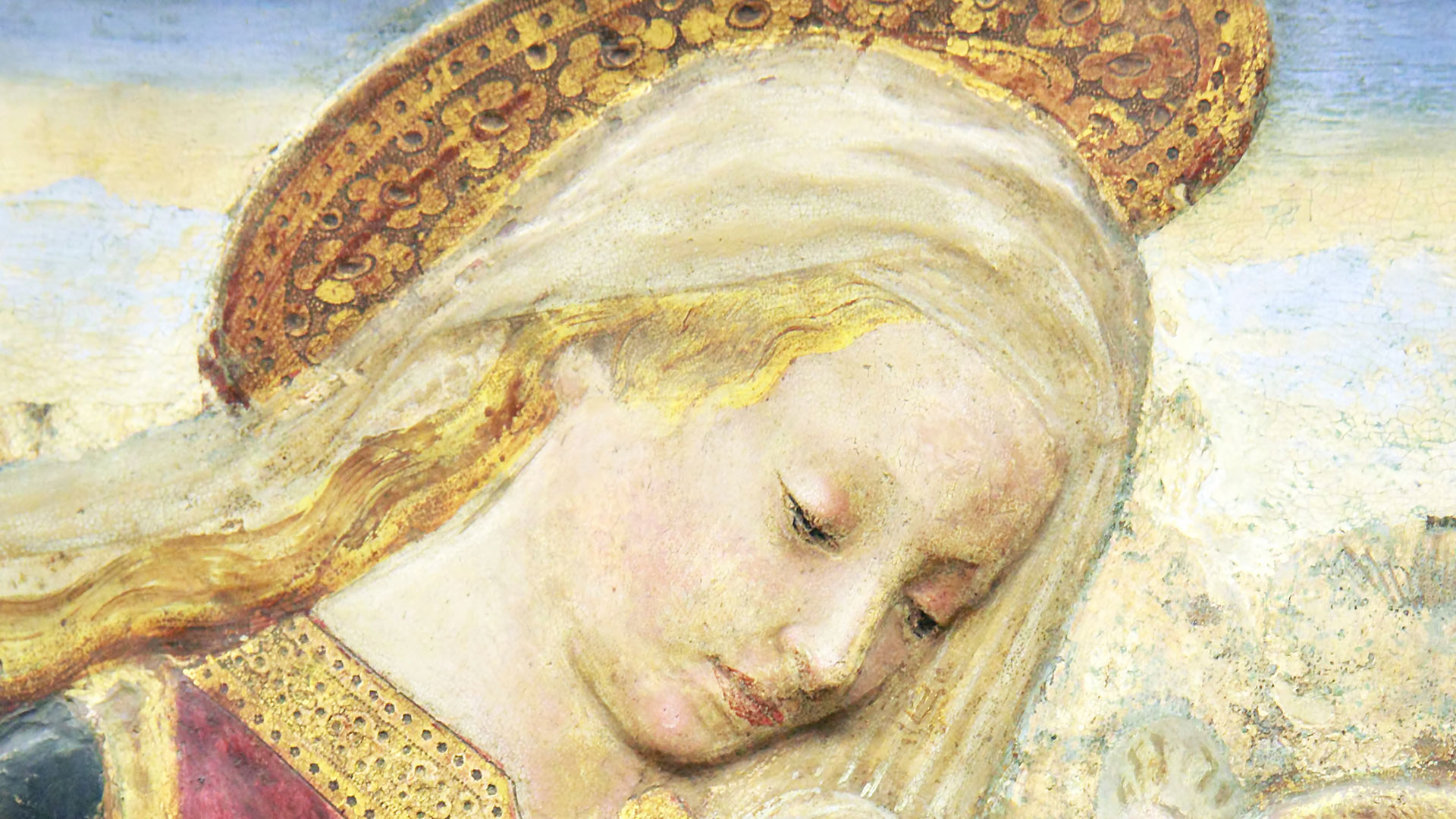

First, great effort is being expended to correct a traditional slur against her; namely, that she was a prostitute before becoming a follower of Jesus. Three separate female characters have, by tradition, been conflated into one: Magdalene herself, from whom Christ exorcised seven demons (Luke 8:2); the otherwise unidentified “sinner” who anointed and wiped Christ’s feet in the presence of a Pharisee (Luke 7); and Mary of Bethany (John 11:1). This conflation has been traced primarily to a sermon by Pope Gregory I in 591. As a result, Mary Magdalene became the patron of reformed prostitutes and other “fallen women” and was often portrayed in paintings, clothed in scarlet and carrying an alabaster jar of ointment.

A quiet retraction by the Roman Catholic Church in 1969 fell well short of eradicating the widely held tradition. The tag of “repentant fallen woman” had become indelibly marked on her. It is interesting, however, that while feminists who take an interest in Mary Magdalene are quick to distance her from the sinful woman who anointed Christ’s feet, some find it convenient to retain the connection with Mary of Bethany in spite of evidence to the contrary.

A second reason for the movement to elevate Mary Magdalene’s significance is that her role, even as portrayed in the canonical Gospels, is generally viewed today as having been minimized by an all-male religious establishment. However, there is a broad spectrum of views about how Mary should now be considered, even among her champions.

Perhaps foremost, however, is that the Mary portrayed in some Gnostic texts—particularly in the Gospel of Mary—is given significant status that makes her appear spiritually superior to Christ’s apostles. Predictably, this is the Mary who has been eagerly elevated as the cause célèbre of feminist writers. This Magdalene is the new queen of heaven in the vanguard of a determined agenda to change our understanding of history, Christianity and the very nature of God.

The Mary portrayed in some Gnostic texts . . . is given significant status that makes her appear spiritually superior to Christ’s apostles.

So how would her advocates have us understand Mary Magdalene and the events—of which she was a part—that are central to Scripture? Do they have a good case, or is it flawed? How does it compare with biblical accounts? What are the implications for mainstream Catholic or Protestant belief?

The Real Mary

Mary Magdalene is mentioned in all four Gospels. This distinguishes her from a confusing bevy of other Marys, including Mary of Bethany. In the Scriptures, the latter is invariably associated with her sister Martha or her brother Lazarus, or with Bethany itself.

The first mention of Magdalene is found in Luke’s Gospel: “Now it came to pass, afterward, that He went through every city and village, preaching and bringing the glad tidings of the kingdom of God. And the twelve were with Him, and certain women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities—Mary called Magdalene, out of whom had come seven demons, . . . and many others who provided for Him from their substance” (Luke 8:1–3).

This passage makes it clear that Magdalene, along with several others, accompanied Christ as He preached the gospel over what was probably a considerable period. And it tells us that He had exorcised her of demons.

Magdalene is also depicted at the crucifixion in all four Gospels, faithfully standing by the brutalized and dying Christ with other women.

Her main claim to fame, however, is that she was the first witness of the resurrected Christ, as recorded in John 20:16–18 and Mark 16:9. According to John’s account, “Jesus said to her, ‘Mary!’ She turned and said to Him, ‘Rabboni!’ (which is to say, Teacher). Jesus said to her, ‘Do not cling to Me, for I have not yet ascended to My Father; but go to My brethren and say to them, “I am ascending to My Father and your Father, and to My God and your God.”’ Mary Magdalene came and told the disciples that she had seen the Lord, and that He had spoken these things to her.”

There was a second, later encounter, recorded in Matthew 28:9–10, where two women (Magdalene and apparently Christ’s mother) saw Jesus. This is often confused with Mary’s first meeting and is seen as a contradiction. But on this occasion He allowed them to touch Him, indicating that He had by then been to His Father: “And as they went to tell His disciples, behold, Jesus met them, saying, ‘Rejoice!’ So they came and held Him by the feet and worshiped Him.” This time both Marys were to convey a further message to the disciples: “Then Jesus said to them, ‘Do not be afraid. Go and tell My brethren to go to Galilee, and there they will see Me.’”

The Apostle Mary?

Because she was the first to encounter the risen Christ and was sent by Him with a message to the apostles, Mary Magdalene has assumed immense importance in the feminist cause. Yet there is an irony here. The designation “apostle to the apostles” (an apostle being “one sent”) was attached to Mary by Roman Catholic church fathers such as Hippolytus and Augustine in the third and fourth centuries. But according to Mary’s advocates, it was the Gnostics who venerated her, whereas the church was guilty of having downplayed her importance.

Mary’s title of “apostle to the apostles” fell out of fashion after Pope Gregory equated her with the sinful woman of Luke 7, but it was given new life by Pope John Paul II in a 1988 Apostolic Letter. Yet the pope quite clearly did not regard the epithet in the same way feminists do: in 1995, he expressly prohibited discussion of women entering the priesthood.

Mary Magdalene is variously treated by the writers of recent books. Likewise, the standards of scholarship and factuality vary as they might in any other field of endeavor, but the range of quality is wider simply because some have hitched their favorite social causes to the research, translation and analysis done by others (much to the irritation of the latter). These causes include radical feminism, antichurch (particularly anti-Catholic) biases, the movement to allow women into the priesthood, New Age and neo-Gnostic sentiments, and ever-present conspiracy theories.

In general, contemporary writers rely heavily on Gnostic documents in their efforts to elevate Mary Magdalene. It is important to understand, however, that these documents differ considerably. Some are cogent, whereas others are unintelligible. Nor do the manuscripts necessarily agree with one another, as there were different branches of Gnosticism. In other words, the standard is extremely uneven. For this reason, modern quotations from Gnostic works tend to be quite narrow and selective.

It is on the basis of this selective reading and interpretation of apocryphal writings that a number of feminists have reconstituted Magdalene as Christ’s consort; as the mother of His child; as the high priestess of a religion where she represents the “sacred feminine” side of humankind; and, ultimately, as the queen of heaven now at Christ’s side. Yet even the Gnostic writings fall far short of any such claims.

The Makeover

On the creative end of the scale, Lynn Picknett, author of Mary Magdalene: Christianity’s Hidden Goddess, transforms Magdalene into a high priestess by alternately quoting the canonical Gospels when it suits her purpose, and rejecting them as the biased account of “the winners of history” when they do not. Mary Magdalene has to be conflated with Mary of Bethany to fit her theory. The latter’s act of anointing Christ’s feet and wiping them with her hair is transformed into both a public display of sexual license and simultaneously a secret anointing that proves Mary was an eastern mystical priestess. And it was all done in front of 12 disciples who were apparently such dullards that their only concern was the cost of the ointment.

The huge leaps of logic are compounded: “Mary of Bethany made Jesus into the Christ by anointing him with spikenard that had, almost certainly, been specifically bought and kept for that purpose” (emphasis added throughout). Another statement on the same page is just as blatant: “Both [John the Baptist and Mary of Bethany] are deliberately marginalized by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John—and so is Mary Magdalene, who comes out of nowhere virtually to take charge of the events after the crucifixion.”

Having stretched the credibility of her assumptions to breaking point via no facts in particular, Picknett continues, “Clearly, this woman who anointed Jesus was very special, a great priestess of some ancient pagan tradition.”

Mary Magdalene’s development as a penitent suited the Counter-Reformation need to emphasize penance and merit over the troublesome notion of grace.

A writer who is less inclined to take such liberties is Dutch Reformed minister Esther de Boer, though she, too, reaches some unfounded conclusions. Her book, Mary Magdalene: Beyond the Myth, is nonetheless informative in a feet-on-the-ground way. She points out that Mary Magdalene’s development as a penitent suited the Counter-Reformation need to emphasize penance and merit over the troublesome notion of grace that had been introduced by the Protestants.

De Boer places Magdalene in the historical and social context of her day: women are introduced into the Gospel accounts in a restrained way because of the first-century social milieu in Judea. Neither Jewish nor Roman tradition allowed for women as witnesses. She adds that the Gospels do not even refer to women as disciples except when they are part of a group that includes men.

De Boer is not interested in unfounded conspiracy theories. “What conclusion are we to draw from the fact that the evangelists [in the Gospels] tell us so little?” she asks. “The most obvious reply would be that the evangelists thought that any further information about her was unimportant for the story of the belief in Jesus that they wanted to tell.”

Susan Haskins, author of Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor, suggests that the financial support that certain women, including Mary Magdalene, were able to extend to Christ may indicate that they were financially independent and therefore of a mature age. As for the belief that she was a reformed prostitute, Haskins points out that this was a convenient idea in an ecclesiastical environment that was coming to view celibacy as the ideal human state.

Haskins also discusses the notion that Mary Magdalene may have married Christ. This theory was posited in Holy Blood, Holy Grail (1983) by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln. Haskins describes the book as “one of the more bizarre manifestations of the late twentieth-century popular interest both in the story of Christ and in conspiracy theory.” The authors conjecture that Mary became the “holy grail” by bearing Christ’s child or children, then went to France, where the Merovingian line of kings was established through the offspring of the “royal couple.” Subsequently there arises the Priory of Sion to defend these secrets, along with alleged documents of the Knights Templar. These flawed notions form the basis of some of the supposed facts claimed by Dan Brown in his Da Vinci Code.

Haskins exposes the idea of Mary having lived in France as a series of tales—wildly conflicting—that monks put out over the centuries. With various shrines and churches vying for the lucrative pilgrimage trade, each had a vested interest in claiming to possess Mary’s remains, or relics.

But Haskins, too, jumps on the bandwagon of the Magdalene remake. Mary “has emerged in bold relief, restored to her New Testament role as chief female disciple, apostle to the apostles, and first witness of the resurrection,” she writes. Yet the New Testament says nothing about the first two of these three assumed roles.

Restoring Mary

It is unfortunate that competing belief systems—one ancient and one modern—have manipulated what little we know of Magdalene to advance their own religious and social agendas. In the case of the Roman Catholic Church, its negative portrayal of Mary over the centuries is essentially a thing of the past. In the meantime, however, radical feminists at last have a female character that they can mold in their own desired image. By resorting to writings of uncertain origin and quoting very selectively from them, without any regard to context, they have reconstructed her to meet a New Age, revisionist and feminist agenda.

For instance, the report in the Gospel of Philip about Jesus kissing Mary is interpreted as proof of a sexual or marriage relationship without any regard to the fact that the same gospel speaks with contempt of sex because it is a physical act. Kissing as a form of greeting, on the other hand, is referred to in other Nag Hammadi texts as well as in the writings of the apostles Paul and Peter (Romans 16:16; 1 Peter 5:14).

James Robinson, professor emeritus at Claremont Graduate University, spearheaded much of the translation and research work in the Nag Hammadi texts. He therefore knows and understands the context of the writings. He says that “the later [Gnostic] Gospels do not imply, much less divulge, any sexual tie with Jesus. The rehabilitation of Mary Magdalene in modern times to her rightful position as Jesus’ very loyal disciple, who stuck with him to the bitter end, should not be trivialized (or sensationalized) by projecting on her what may be no better than one’s own sexual fantasies.”

So how are we to view Mary of Magdala? In the Apostolic Writings, we read of her presence at the events surrounding Christ’s death and resurrection. She then disappears from the scene, simply because she is no longer an important part of the ensuing accounts. In short, the Mary Magdalene of the Bible is portrayed as neither more nor less than a devout follower of Christ.