Israel Exiled

As we’ve seen in earlier installments in this series, the ancient Israelites were warned from the time of Moses that idolatry would lead to the nation’s downfall. Yet, despite similar prophetic warnings over the next centuries, they chose to follow the gods of the nations around them. The results are entirely predictable.

Last time we noted the continued slippage in northern Israel’s allegiance to God, specifically under the house of Jehu in the latter half of the ninth century BCE, through to the reign of Jehoash (800–784).

A similar pattern of compromise became evident in the reign of Amaziah, the new ruler in the southern kingdom of Judah. Though the Jewish king “did what was right in the sight of the Lord,” he wasn’t fully loyal in that he didn’t remove the pagan altars and high places—hilltop sanctuaries—where the people continued to worship. He correctly spared the children of his father’s assassins according to the law of Moses, which specified that people should bear the consequences of their own sin; yet in victory over the neighboring Edomites, he returned with their gods and began to worship them (2 Kings 14:1–7; 2 Chronicles 25:1–4, 14).

Despite a warning from an unnamed prophet, Amaziah insisted on going his own way. The prophet knew from that moment “that God has determined to destroy you” (2 Chronicles 25:15–16).

Next, emboldened by his recent triumph in Edom, Amaziah provoked a foolhardy war with his Israelite counterpart in the north, Jehoash (spelled “Joash” in Chronicles). Because of pride and his dalliance with the Edomite deities, Amaziah came to grief when Jehoash captured him and returned with him to Jerusalem, broke down part of the city’s wall, and carried away hostages and the treasures of the temple and royal household (2 Chronicles 25:20–24; 2 Kings 14:8–14). Chastened but free to continue as king in the south, Amaziah outlived Jehoash by 15 years. During that time, Jehoash’s son, Jeroboam II, ruled the northern tribes and would continue for a further 26 years.

In retribution for his departure from God, Amaziah ultimately became victim of an internal conspiracy in Judah and was murdered. His son and successor, Azariah, also known as Uzziah, was a mere 16 years old at the time. Notably, he soon rebuilt the Red Sea port of Elath, restoring it to Judah. He was to rule for 52 years, often emulating the good aspects of his father (2 Chronicles 25:27; 2 Kings 14:19–22, 15:1–2). It’s recorded that “he sought God in the days of Zechariah [not the minor prophet], who had understanding in the visions of God; and as long as he sought the Lord, God made him prosper” (2 Chronicles 26:5).

Uzziah gained fame in the region for his agricultural developments, his building programs and his military prowess. Yet he also failed to remove the high places and became filled with pride. In his arrogance he tried to burn incense on the temple’s altar, a role reserved for the priests, and this act proved to be a major turning point in his rule. He was struck with leprosy, forcing him to live in isolation while his son carried out the day-to-day rule (2 Kings 15:3–5; 2 Chronicles 26:6–21).

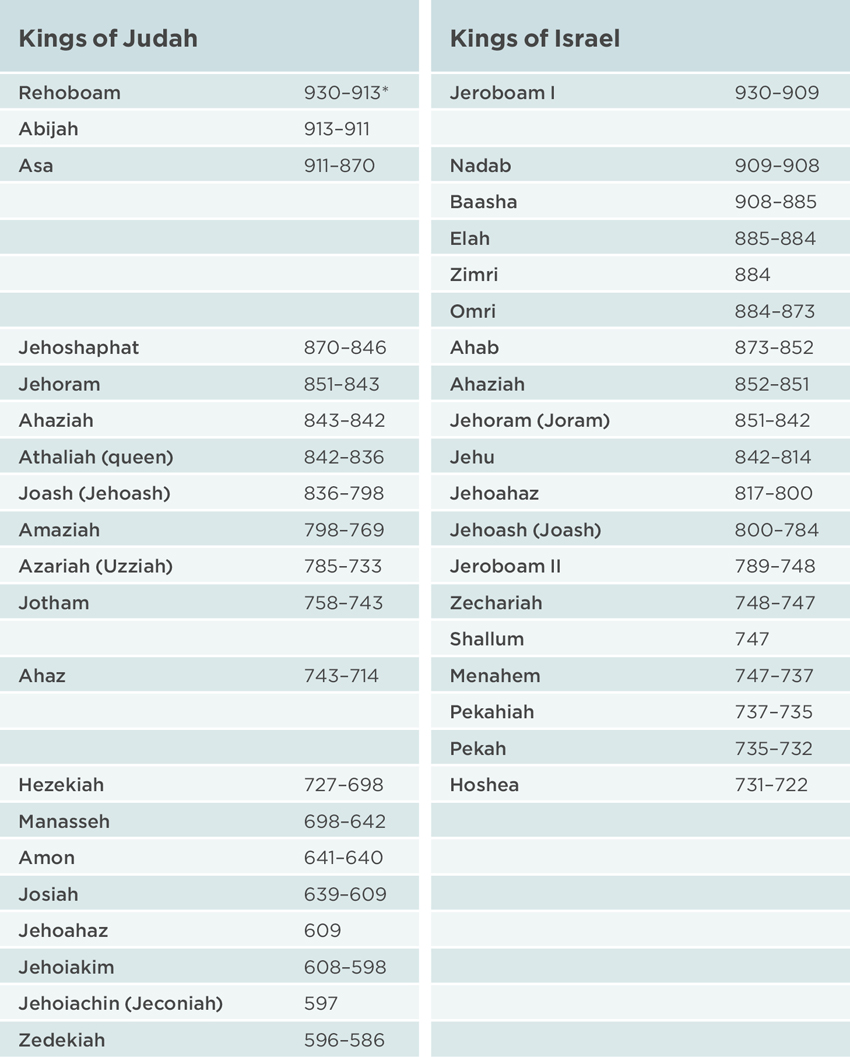

After the reigns of Saul, David and Solomon, the ancient kingdom of Israel was divided between north (Israel) and south (Judah). Listed above are the monarchs who ruled over the divided kingdom. *Dates are approximate; all dates are BCE.

Adapted from A Biblical History of Israel by Iain Provan, V. Philips Long and Tremper Longman III (2nd ed., 2015).

Prophets Speak Out

The prophet Amos is mentioned in connection with Uzziah and the latter days of Jeroboam II (Amos 1:1). Though he was a Judean, Amos’s message concentrated mostly on the northern Israelites, to whom he announced that captivity was coming. Secondarily he addressed the sins of Judah and several surrounding nations. Amos is listed among the Bible’s 12 minor prophets (from the Latin minor, “smaller” [in length of book]).

In Uzziah’s final year, the well-known major prophet Isaiah was commissioned (Isaiah 6:1–9). He spoke during the subsequent reigns of Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah (Isaiah 1:1), delivering messages about the coming downfall of Judah and Jerusalem, its expected Messiah, and the future kingdom of God.

Another prophet, Hosea, was active a little later, focusing mainly on the northern kingdom of Jeroboam II, though he is also mentioned in connection with Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah, kings of Judah (Hosea 1:1). Again, the purpose of most of his pronouncements was to warn the northern tribes, often referred to collectively as “Ephraim,” of their coming destruction and exile.

During Jeroboam’s reign, God spoke through the minor prophet Jonah as well. He is best known for his reluctant prophetic mission to the significant regional power, Assyria, and its capital, Nineveh, during which he famously encountered a great fish (Jonah 1–3). Much to Jonah’s chagrin, Assyria changed course at his public warnings and avoided punishment, forestalling their eventual invasion of Israel and deportation of its inhabitants. Jonah would have preferred to see them destroyed rather than achieve what he expected for his own people at their hands. But God chided him for his unmerciful attitude: “Should I not pity Nineveh, that great city, in which are more than one hundred and twenty thousand persons who cannot discern between their right hand and their left—and much livestock?” (4:11).

“The prophets . . . considered themselves spokespersons for Yahweh, who through them called his people back to obedience to the covenant he had given them many centuries before.”

Jonah also prophesied the recapture of Israel’s territories from Hamath to the Dead Sea (2 Kings 14:25). Though we do not know which of these two prophetic missions came first, perhaps they are interrelated. The fact of Nineveh’s willingness to hear the word of an Israelite prophet, the fact of Israel’s recovery of land, and the accompanying statements that “there was no helper for Israel” and “the Lord did not say that He would blot out the name of Israel from under heaven; but He saved them by the hand of Jeroboam” (14:26–27) may explain why the Assyrians did not attack in Jeroboam’s time. Though his rule was comparable to that of his corrupt namesake, who had led Israel into idolatry when the northern tribes first seceded, God in His mercy determined not to bring Israel down just yet.

The Beginning of Israel’s End

When Jeroboam II died, he was succeeded by his son, Zechariah, who was murdered after a mere six months by Shallum. This fulfilled a prophecy that God had made to Jehu, to the effect that he would have successors only to the fourth generation (2 Kings 10:30, 15:12). Shallum lasted just one month in Samaria before he in turn suffered assassination at the hands of Menahem, who reigned for the next decade, continuing in the pagan ways of Jeroboam I. It was then that the Assyrians, under Tiglath-Pileser (also known as Pul or Pulu), descended on Israel, intending to attack it. Desperate for Assyrian support, Menahem paid Pul one thousand talents of silver that he later exacted from the wealthy in Israel. Satisfied for the moment, the Assyrian king and his army returned to Nineveh (15:13–20).

Next in line came Menahem’s son Pekahiah, who ruled for two years, only to be murdered by Pekah, who as king had to face another visit from Tiglath-Pileser. This time the Assyrian took territory and people in northern and eastern Israel, including “Ijon, Abel Beth Maachah, Janoah, Kedesh, Hazor, Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali; and he carried them captive to Assyria” (verse 29).

In the south, Jotham ruled Judah during Pekah’s reign. The positive assessment of his reign compared him to his father, Uzziah. He was a successful builder of cities and defenses, and a conqueror of the Ammonites, whom he put under tribute. Yet as with several other kings, he failed to remove the high places and prevent worship there. We are told that under him the people still “acted corruptly.” It was then that God allowed pressure from both Syria and Israel to be applied to Judah (2 Kings 15:32–37; 2 Chronicles 27:1–6). With three years left in Pekah’s rule, Jotham died and was succeeded by his son, Ahaz.

The minor prophet Micah spoke during the reigns of Jotham, king of Judah, and his successors Ahaz and Hezekiah, but his messages were directed toward both Samaria and Jerusalem (Micah 1:1).

“Of prime importance to the writer in his presentation of prophecy is the fulfillment of the prophetic word in the history of the two nations for good or ill.”

Ahaz proved to be an idolater who “walked in the way of the kings of Israel” during his 16-year reign. He even practiced ritual immolation of children, including his own. The Syrians and northern Israelites attacked once more, and though they failed to capture Jerusalem (see Isaiah 7:1–6), they did take captive many of Judah’s inhabitants, exiling them to Damascus and Samaria. They killed the king’s son and drove Judah from Elath, reinstalling the Edomites there. But the northern tribes released their captives after a prophet brought God’s warning message to them (2 Kings 16:3–6; 2 Chronicles 28:1–15).

Ahaz’s response to the attack was to request aid from Tiglath-Pileser, paying for it by sending him treasures from the temple and from his own house. At first the Assyrians did nothing to help; but then they captured Damascus, exiled some of its people, and killed Rezin, king of Syria.

Afterward Ahaz visited Tiglath-Pileser in Damascus, and seeing an altar there, he had a copy made and installed in the Jerusalem temple precinct, moving the original bronze altar to another location nearby. He would use the original to seek oracles but commanded the priesthood that all daily offerings and sacrifices be made on the new Damascus-style altar. He introduced other changes to the temple area, some, it seems, in deference to the Assyrian king, the conqueror of northeastern Israel, to whom he was now subservient. In the end he departed from following God entirely, sacrificing to the gods of the Syrians and setting up altars to them in Israel (2 Kings 16:7–18; 2 Chronicles 28:16–25).

The Northern Kingdom Falls

In the north, Pekah’s reign had come to an inglorious end when Hoshea conspired and murdered him, taking over the throne (2 Kings 15:30). His accession in 731 was the beginning of the end of the line for the northern kingdom. Four years later, Shalmaneser became king of Assyria. At first Hoshea was happy to pay tribute to avoid war with the Assyrians. But after a couple of years, he secretly allied against them with Egypt and refused to make further payments. Discovering the subterfuge, Shalmaneser imprisoned him and began a three-year siege of Samaria (17:3–5).

The end came when “in the ninth year of Hoshea, the king of Assyria took Samaria and carried Israel away to Assyria, and placed them in Halah and by the Habor, the River of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes” (verse 6). This was around 722/21, when Sargon II usurped the throne and thus succeeded Shalmaneser.

Northern kingdom of Israel taken captive to Assyria, late 8th century BCE

Adapted from Bound for Exile: Israelites and Judeans Under Imperial Yoke by Mordechai Cogan (2013).

Some Assyrian records mention that Sargon, not Shalmaneser, took the Israelites captive. How is this to be understood? It may be that Sargon wanted to embellish his list of achievements and legitimate his rule, and that he therefore incorporated his predecessor’s success. Or it may be that the biblical account is a simplified version of what happened, focusing on the initiator of Israel’s collapse.

In any event, the author of 2 Kings gives the reason for the end of the kingdom and the exile: the worship of foreign gods, establishing high places for idolatry, stubborn refusal to change, rejection of God’s law, and witchcraft and divination (verses 7–18). He concludes, “So Israel was carried away from their own land to Assyria, as it is to this day” (verse 23). Writing about 300 years later, the author of Chronicles indicates that this was not the totality of the population, because some had “escaped from the hand of the kings of Assyria” (2 Chronicles 30:6; compare 34:9).

Though the southern kingdom represented probably most of what was left of ancient Israel, they also “did not keep the commandments of the Lord” (2 Kings 17:19). Eventually they, too, would be sent into exile.

In the meantime, as was Assyrian practice, the captured land in the north would be resettled by others in forced migrations. This transfer of populations “brought people from Babylon, Cuthah, Ava, Hamath, and from Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel; and they took possession of Samaria and dwelt in its cities” (verse 24).

These new inhabitants retained their versions of pagan worship and the gods of their places of origin. When adversity struck, they thought they needed to placate Samaria’s local deities, but they didn’t know how. Ironically, the Assyrian king’s solution was to return an exiled Israelite priest to teach them (verses 26–28). Recall that Jeroboam had set up his own priesthood and corrupt form of religion when Israel first broke from Judah (1 Kings 12:26–33); Israel’s priests had themselves strayed far from God, and this is what led to the nation’s exile in the first place.

In any case, this solution proved to be of dubious value; having learned somewhat, the new inhabitants appointed their own priests and continued with a blend of religions: “So these nations feared the Lord, yet served their carved images; also their children and their children’s children have continued doing as their fathers did, even to this day” (2 Kings 17:29–33, 41).

Next time, Judah succumbs to the same fate as its northern cousins.