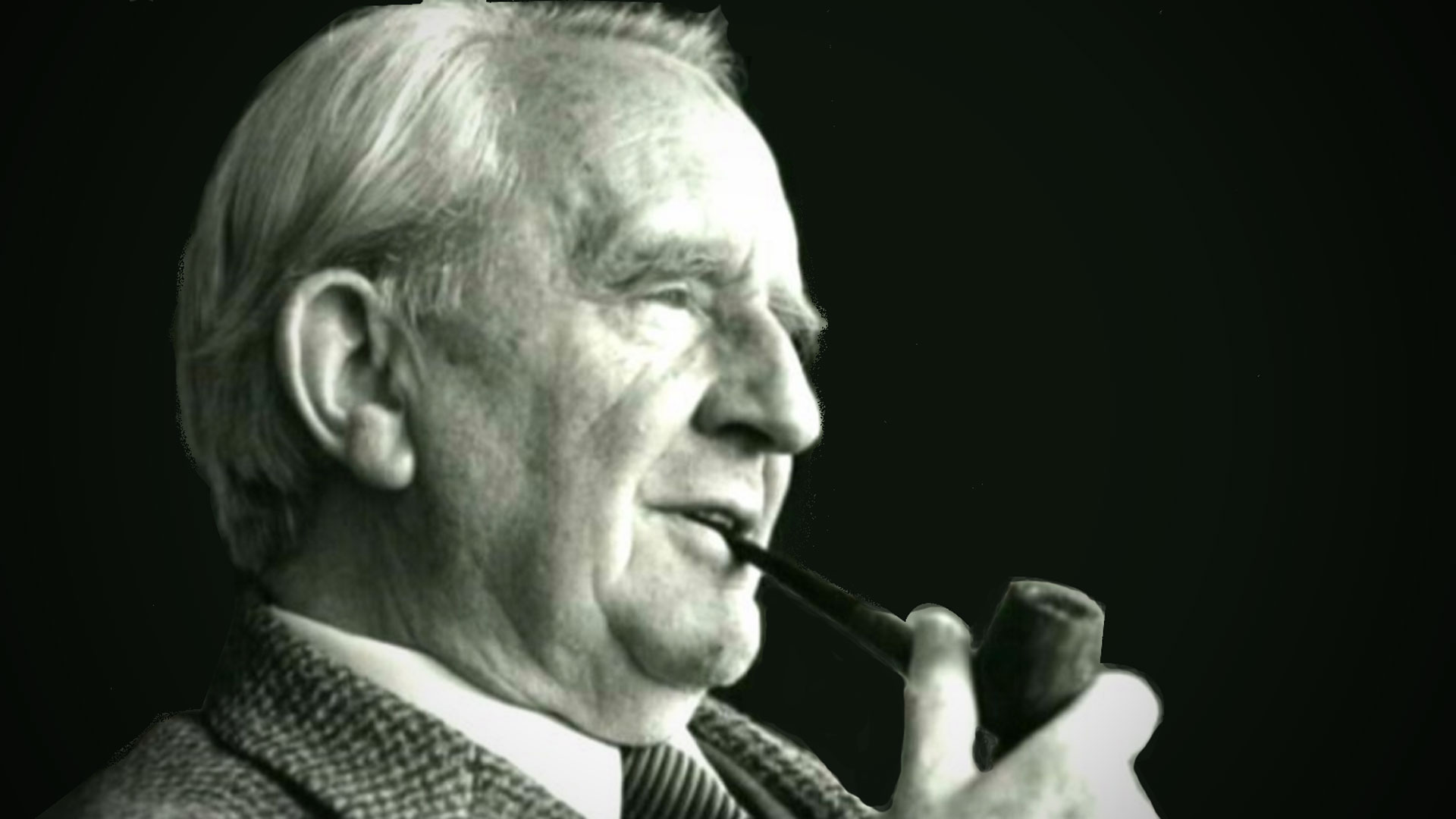

J.R.R. Tolkien: Speaker of Footnotes

As an undergraduate student of Magdalen College at Oxford, George Sayer was given advice from his tutor, author C.S. Lewis. The respected tutor had a very low opinion of the sessions that were presented in Oxford’s hallowed classrooms and therefore discouraged Sayer from attending many of them. The student was instructed to attend only those lectures given by Lewis himself, by Nevill Coghill, and by a professor of Old English by the name of Tolkien.

Lewis, however, did have some reservations about the latter. He told Sayer that Tolkien “could be brilliant though perhaps rather recondite for most undergraduates,” and that he was essentially a bad lecturer. Despite these concerns, the tutor advised his pupil to attend the professor’s lectures because of his many extemporaneous remarks and comments. Lewis said wryly that these were “usually the best things in the lecture. In fact one could call him an inspired speaker of footnotes.” It was this knack for stepping outside the box, coupled with his keen attention to detail, that later enabled Tolkien to create not only a gripping story but an entirely new world for his readers.

Born in 1892 in Bloemfontein, South Africa, to Arthur and Mabel Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had only slight recollections of his time there. His family moved back to his father’s native England shortly after his birth.

Because both parents died while he was still a boy, he and his younger brother came under the care of a local Roman Catholic priest. Under his guidance Tolkien was nurtured in the Catholic faith, and he remained a devout Catholic his entire life. His early experiences and religious training would directly influence his life and his writings.

Tolkien possessed a gift for linguistics, which allowed him to master Latin and Greek and then other ancient languages. Combining this love of language with his proclivity for creative and extensive detail, he developed his own languages, complete with rules and guidelines for usage. At 19 he enrolled at Exeter College in Oxford, focusing on Old English, Welsh, Finnish and the Germanic languages. His studies introduced him to the myths and lore of these and other countries, supplying food to his fertile imagination.

Tolkien was enchanted with the stories of ancient races, tales of epic wars between gods and men, and noble deeds accomplished in desperate circumstances. In 1917 he began to write down some of the stories that would become the background for his subsequent works. The book, eventually known as The Silmarillion, outlined the many characters and elements that would be introduced in his later stories as if they were history. It was filled with poems, oral histories, mythologies and narratives about the creation of the world. Within the pages of this early work was the first appearance of a place known as Middle-earth, a legendary land complete with its own languages, creatures, histories, myths and cultures.

After World War I, Tolkien sought and obtained work in the academic field. He served for a short time as an assistant lexicographer on what became known as the Oxford English Dictionary. In 1920 he was accepted as an associate professor in English language at Leeds University, and five years later he returned to Oxford to serve as professor of Anglo-Saxon. He would hold this title for 14 years. From 1945 to 1959, he was a professor of English language and literature at Pembroke College, Oxford.

During the 1930s Tolkien began to socialize with a group of mostly like-minded writers connected with Oxford, known as the Inklings. The group would meet each week for readings, critiques of one another’s work, drinks, and conversation. Among its other members were such notable talents as C.S. Lewis (who became Tolkien’s closest friend), Charles William, Owen Barfield and Nevill Coghill. Tollers, as they called Tolkien, would read aloud some of his poems and stories. The Inklings were captivated by his ability to describe so extensively this world filled with the hairy-footed, pint-sized people known as “hobbits.”

The Hobbit was published in 1937. After its initial success, the publishers wanted Tolkien to continue to write about these interesting creatures. He presented them with portions of The Silmarillion, but the work was rejected as not being commercial enough for publication. So with The Silmarillion providing the background story, Tolkien began to write a sequel to The Hobbit. It actually became a more complex story, with dark overtones quite unlike the earlier book. For the next 16 years, Tolkien labored on what would become his masterwork, The Lord of the Rings.

He originally intended that the work be published as one volume, but because of the immense length of the manuscript, the book was published as a trilogy: The Fellowship of the Rings (1954), The Two Towers (1954), and The Return of the King (1955).

The Lord of the Rings was considered a modest success in its initial publication. While it generally received positive reviews, Tolkien’s work was not considered anything more than a unique story with limited appeal. It was not until 1965, when the books were published in paperback form (without permission) in the U.S., that his work found an audience. The book went on to sell millions of copies worldwide.

J.R.R. Tolkien died on September 2, 1973, and was buried alongside his wife in Oxford. The immense popularity of the movie trilogy has returned him to the center of modern Western culture, and his influence will continue to be debated in intellectual circles. But however one views his work, it is clear that Tolkien’s new literary genre has captured the imagination and minds of generations of readers, many of whom would love to live in his imaginary world.

The immense popularity of the movie trilogy has returned Tolkien to the center of modern Western culture.

While The Silmarillion would not be published until four years after his death, Tolkien continued throughout his life to expand his vision of Middle-earth and its inhabitants. His hope was to someday publish it as a single volume. His son Christopher would later recollect that his father “never abandoned it, nor ceased even in his last years to work on it.” Tolkien’s vivid and detailed vision of Middle-earth was fed from a wide variety of influences and a vast collection of sources. There is no doubt that had he lived on, the man who was called “the speaker of footnotes,” would have continued to add to the complex texture of his imaginary land.