Repercussions of Revenge

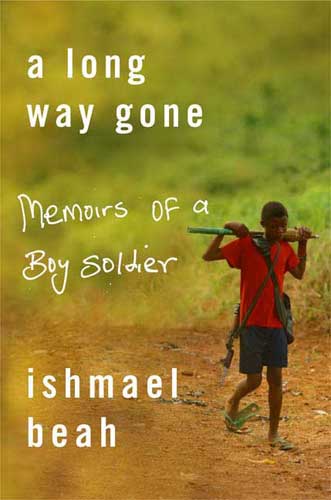

A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier

Ishmael Beah. 2007. Sarah Crichton Books, New York.

Former Liberian president Charles Taylor’s trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Sierra Leone has begun in The Hague. It follows the recent release of a book by one of the war’s victims, former child soldier Ishmael Beah. The brutal, decade-long civil war, which began in 1991, is notorious for such ruthless tactics as the terrorizing and maiming of civilians and the forcible recruiting of young boys. As many as 10,000 children under the age of 18 were used as soldiers in this bloody West African conflict.

Ishmael was 12 years old when the war reached his village in January 1993. Fourteen years later, he has recorded his story in A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. His moving book is a tale of survival. Separated from his family in the chaos, he and his friends fled the attacking rebels, known as the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), who were supported by Taylor in neighboring Liberia. The young boys understood that they were at risk of capture by the rebels, who raped, mutilated and killed civilians and forced their young “recruits” to do the same. What the displaced boys did not anticipate was the hostility they received from the rest of the population. In a society terrorized by the barbarous acts of young RUF conscripts, all young boys were feared, so village after village greeted them with machetes and spears, even though the boys, too, had witnessed the violent aftermath of RUF attacks, and had found their own families and friends murdered.

After months of hunger and narrow escapes, the boys at last found refuge in a village occupied by the government army. But as casualties mounted, they were forced to fight or flee. They were trained alongside other boys as young as 7 years old and taught to “visualize the enemy, the rebels who killed your parents, your family, and those who are responsible for everything that has happened to you.” They were shown violent movies, given their own AK-47s, and supplied with amphetamines, marijuana and “brown brown,” a combination of gunpowder and cocaine. Before long, “killing had become as easy as drinking water.”

Ishmael reflects, “My squad was my family, my gun was my provider and protector, and my rule was to kill or be killed. .&bnsp;.&bnsp;. My childhood had gone by without my knowing, and it seemed as if my heart had frozen.”

Therefore when UNICEF workers brought him from the front lines to a rehabilitation home after two years of fighting, a necessary long and difficult process of transition began in which he would begin healing from the trauma of war and discovering his true identity. In the early stages, he mourned his squad and resented the aid workers. But the center’s patient approach saw him through two desperate months of drug withdrawal, frequent nightmares, and insomnia, and it provided the space and the means to heal from the physical and emotional scars of war. The center also provided physical and psychosocial care: medical care for his wounds, medicine to help him sleep, and the opportunity to discuss his experiences. It took months before his mind was ready to think of his family. He learned skills for the workforce and was given the opportunity to be a spokesperson for the center, spreading the message that child soldiers can be rehabilitated. After eight months at the center, he was united with his only remaining relative—an uncle he’d never met.

Ishmael was chosen to represent Sierra Leone at the United Nations First International Children’s Parliament and eventually immigrated to New York City. Now a graduate of Oberlin College, he has become a gifted writer with the ability to vividly portray his experiences. In his extremely readable style, he shares with readers the disappointments, loss, pain, terror and laughter of his remarkable journey.

Ishmael gives a human face to the 300,000 child soldiers currently involved in conflicts around the world. While an increasing volume of literature is available on the subject, his accessible firsthand account enables the reader to empathize in a way that is rare in academic studies. Though each experience is unique, Ishmael’s easy writing style provides a tangible window into the world of child soldiers.

His book is also a commentary on war, which results in the evaporation of social norms and trust. The author makes it clear that it is not only he who is a long way gone, but the entire society is a long way from its normal standards and practices. As one old man told him, “This country has lost its good heart. People don’t trust each other anymore. Years ago you would have been heartily welcomed in this village.” Instead, 12-year-old boys were left to starve by the very communities that should have protected them. Ishmael writes, “This was one of the consequences of the civil war. People stopped trusting each other, and every stranger became an enemy.”

A Long Way Gone is the story of a special young man who lost his childhood but gained deep wisdom and understanding beyond his years. In an address to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), a teenaged Ishmael summed up his experience in a profound statement that, if acted on, would end many conflicts around the world: “What I have learned from my experiences is that revenge is not good. I joined the army to avenge the deaths of my family and to survive, but I’ve come to learn that if I am going to take revenge, in that process I will kill another person whose family will want revenge; then revenge and revenge and revenge will never come to an end.”