Superbugs

An Emergency of Our Own Making

The rise of drug-resistant superbugs threatens the efficacy of antibiotic therapies, but solutions require confronting not just scientific challenges but approaches to current therapeutic practice itself.

A microbial enemy invisible to the naked eye is projected to kill millions of people and cost US$1.7 trillion a year by 2050. So says a report issued by the Center for Global Development think tank. The damage won’t be caused by war, famine or climate catastrophe but by the rise of “superbugs”—microorganisms (predominantly bacteria) against which current therapies such as antibiotics are ineffective.

Like the climate crisis, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is so complex that it’s difficult to grasp. It’s been described as a “silent pandemic,” a “slow tsunami” or “the flow of molten lava.” The flames of the superbug crisis are now spreading on multiple fronts. Many have sounded the alarm about the urgent need for action.

Yet given the projected severity of this crisis, the most pressing question is not whether we know enough to act but why action has been so difficult to sustain. It’s not due to scientific ignorance. The greatest obstacle to stopping this threat is human nature itself—our short-term thinking, competing interests, and failure to exercise responsible stewardship. Moving forward requires recognizing our shared responsibilities and acknowledging the limitations of solutions that rely on science alone.

The Power to Heal

Not all that long ago, bacterial infections such as tuberculosis and diphtheria were among the leading causes of death. Modern scientific discoveries have given us a sense of security against the threat of infectious diseases, especially for people living in wealthy regions.

A first step in that direction came in the late 19th century, when French chemist Louis Pasteur and German physician and biologist Robert Koch pioneered breakthroughs in “germ theory.”

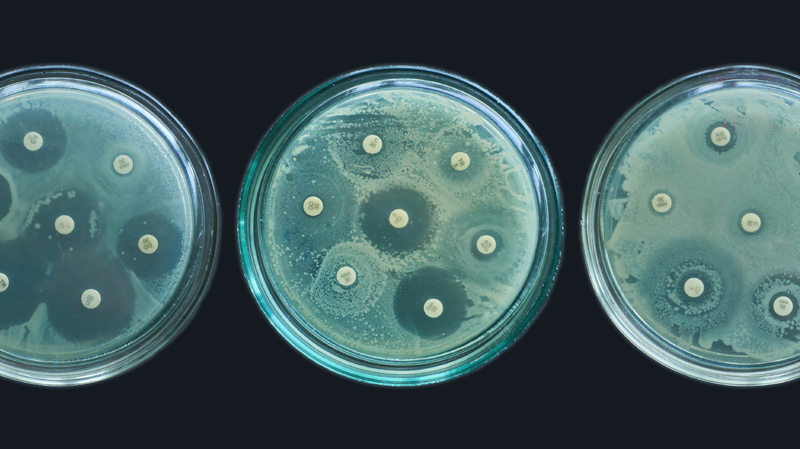

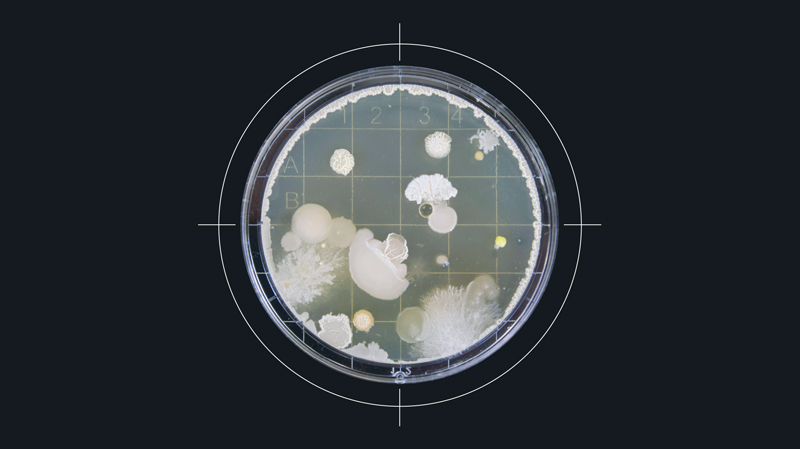

A 1928 discovery by Scottish physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming opened the way to fighting back against bacterial infections. While away on his summer break, Fleming had left a Petri dish containing Staphylococcus bacteria near an open window in his laboratory. When he returned in September, a rare strain of airborne mold, Penicillium notatum, had settled on the sample. Though he observed that the mold would kill a variety of bacteria, Fleming didn’t recognize the full potential of his discovery and abandoned the project by the summer of 1929.

More than a decade later, driven by the urgent needs of World War II, Oxford scientists Ernst Chain and Howard Florey revisited Fleming’s discovery, working to purify the mold and bring it into production. Reflecting on its significance during wartime, Winston Churchill observed in 1944 that penicillin “has broken upon the world just at the moment when human beings are being gashed and torn and poisoned by wounds on the field of war in enormous numbers.” In 1945, Chain and Florey shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Fleming.

“Thanks to penicillin . . . he will come home.”

Interestingly, at one level Fleming’s discovery was something of a rediscovery. Matt McCarthy, a professor of medicine, observes that ancient humans are known to have consumed antibiotics, likely contained in brewed beer, as evidenced from Sudanese mummies dated to 350–550 CE. In Egypt, femoral bones from the late Roman period at the Dakhla Oasis contained traces of tetracycline. McCarthy says that “our ancestors understood the effect of antibiotics, if not the mechanism.”

To understand why Fleming’s discovery was nevertheless so significant, it helps to understand what antibiotics do. As antimicrobials, they act against bacteria. The term microbe is broad and includes bacteria, viruses and fungi. Muhammad H. Zaman, professor of biomedical engineering and international health at Boston University, says that “there are more bacteria on Earth than there are stars in the universe, and there are about 40 trillion in the human body alone.” The mass of those bacteria constitutes about 0.3 percent of our total body weight.

It is a fantastically balanced relationship. Most bacteria are benign or beneficial to humans; we need them. However, when that balance is disrupted, depending on which part of the body they occupy, some bacteria can cause problems.

A Waning Power

The discovery and development of penicillin was game-changing in the battle against bacterial disease. It’s often viewed as a prime example of serendipity—the chance discovery of something profoundly beneficial.

But although penicillin and other antibiotics greatly improved our ability to treat bacterial infections, their effectiveness was always at risk. Upon receiving the Nobel Prize, Fleming linked potential misuse of the drug to a future threat of rising resistance. “The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops,” he said. “Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant.” He concluded with a stark warning—“Moral: If you use penicillin, use enough.”

Fleming understood the risk that misuse would diminish the power of this new tool, and that is precisely what has happened. Whether through under- or overuse, we have ineffectively used antibiotics, reducing their effectiveness.

A common misconception is that it’s our bodies that become resistant to antibiotics. In fact, it’s the bacteria that change and become resistant to the point where the drugs are no longer effective against them. We stand on the precipice of what Margaret Chan, former director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), described as the “post-antibiotic era.”

The problem is projected to reach such a magnitude that failure to solve it is not an option. Procedures such as hip replacements, C-sections and organ transplants rely on antibiotics to protect patients. Yet in a worst-case scenario, the choice of treating cancer would have to be weighed against the risk of catching an untreatable infection.

Danilo Lo Fo Wong, WHO senior regional adviser on antimicrobial resistance in Europe, says that if the situation deteriorates to that extent, then “basically the last 70, 80 years of modern medicine will get lost, and we’ll go back to the era before penicillin was discovered.” In the pre-penicillin era, life expectancy was far below what it is today. Back then, it was possible to die from an infected scratch.

The situation has led to a bitter irony: The hospital, a place designed for human healing, and where antibiotics are administered, is likely to be precisely where superbugs thrive. Such superbugs include the feared methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which can be life-threatening. Studies of the wastewater from some hospitals have found antibiotic-resistant bacteria levels that exceed those in the surrounding community.

“Far from acting to help itself, humanity seems currently to be aiding the superbugs.”

Yet the ironies have begun to run deeper still. Geophysicist Mihai Andrei has pointed to a superbug, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, that has a taste for plastic. According to Andrei, “it can break down polycaprolactone (PCL)—a biodegradable polymer widely used in medical implants—and use it as fuel to grow more powerful. This means that in the very environments meant to heal us, some microbes may be learning to thrive on the materials designed to restore our bodies.” In other words, some microbes are adapting faster than our efforts to contain them; they’re thriving at our expense.

As disturbing as these developments are, the scope of the problem does not end there. As a human discovery held in human hands, the problem is as complex as we are. For example, in some parts of the world, antibiotics are available over the counter, increasing the risk of overuse leading to inefficacy. In other parts of the world, the issue is that antibiotics aren’t available.

Human Systems, Human Consequences

Doctors, meanwhile, often operate under intense pressure. A 2022 study of English doctors published in the journal Medical Decision Making found that the percentage of prescriptions for “broad-spectrum” antibiotics increased by 6.4 percent as pressure on doctors increased. Broad-spectrum antibiotics kill or inhibit a wide range of bacteria. They’re typically used to treat bacterial infections when the group of bacteria is unknown or when multiple types of bacteria are causing infection. While often necessary, these powerful tools can disrupt the body’s bacterial balance and, by exposing more bacterial species to the drug, accelerate the development of resistance.

Yet the problem of overuse extends beyond medical settings. In the decades following Fleming’s discovery, antibiotics began to be used at scale in animal husbandry and aquaculture, and not just to treat sick animals. With limited regulatory oversight, their use soon grew to include the prevention of infection. Researchers discovered that administering antibiotics increased the growth rate in some animals, allowing for intensive farming. Consequently Fleming’s discovery has become integral to the economic viability and yield of the agriculture and food sectors. Antibiotics allow us to feed as many people as we do today, but only by compromising principles of responsible management and reducing the effectiveness of those same antibiotics for all.

This pattern of short-term gain creating long-term crisis reaches into the pharmaceutical industry itself. From a financial perspective, the world of commerce is governed by supply and demand. Corporations, including drug companies, make a product and then push sales to generate higher profits.

But society’s requirement for antibiotics doesn’t follow those profit-focused dynamics. The world needs new antibiotics to come to market in the face of resistance to existing drugs, and it also needs to restrict unnecessary use to prevent further resistance. Both facets are intricately bound up with the complexities of finance and government. Given the huge levels of investment required to bring a new drug to trial phase, the economic system is out of step with what’s needed to solve the problem. As a result, the production of new antibiotic drug classes for human treatment has largely dried up since the mid-1980s.

“A successful response to AMR relies on political commitment, sustainable financing, measuring progress with accountability and most importantly, placing . . . all those affected at the centre of the response.”

Governments have taken steps to raise awareness of the threat of AMR and encourage action, but the persistent issue of political short-termism remains a major obstacle. Policies that yield immediate, visible benefits take precedence over long-term planning and sustainable solutions.

The complexity of the issues for governments is made more challenging by the evolving and disparate nature of the crisis across the globe. The editors of the essay collection Steering Against Superbugs: The Global Governance of Antimicrobial Resistance note that “mitigating AMR is a global concern but strategies to do so depend very much on how AMR appears in specific regions, countries, and even specific localities.”

We may be running out of time. One influential report suggests that in a worst-case scenario, annual deaths related to superbugs may become comparable to those caused by cancer and be as high as 10 million by 2050.

Fighting the Fire

The superbug crisis mirrors the complexity of the human systems it threatens—economic, political and social. To fight it effectively, solutions must be equally multifaceted, including not just scientific innovation but also addressing the structural barriers that hinder effective action.

Market Entry Rewards (MERs) are one possible means of incentivizing drug companies to produce new antibiotics. These programs allow both industry and government to tackle different elements of drug development. Under this system, makers of a new antibacterial drug can receive a lump sum payment when the drug is brought to market.

Advocates believe this model aligns with how we should think about antibiotics. John Rex, an expert on the topic, argues that we should think of antibiotics much like we think of a fire brigade—rarely used, but essential to have ready. Therefore they should be funded in a similar manner. Rex notes: “When you pay the firefighters, do you pay them per fire, or do you pay them a salary? It’s obviously the latter, and the importance of working together at the community level to have a fire brigade ready at all times has been known as far back as Ancient Rome.”

In 2020 the United States government first introduced the Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions To End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act. The Act would authorize “the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to enter into subscription contracts for critical-need antimicrobial drugs,” creating an alternative funding model aimed at incentivizing the production of new antibiotics. Kevin Outterson, executive director at CARB-X (Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator), is an expert on antibiotic resistance. He has said that under the PASTEUR Act, “the company makes the same amount of money no matter how much of the antibiotic is used. . . . And we put that new antibiotic on the shelf as a fire extinguisher: We don’t want to use it until we have to.” The act has not yet passed, however, due to disagreements over several of its elements.

Another notable step toward a solution was the proposal for a One Health approach in the early 2000s, which led to the first One World, One Health conference at the Rockefeller University in 2004. The conference was considered a success because it linked “human, animal and environmental health and stewardship”—an important step in that it recognizes that any true solution must extend stewardship across separate but connected spheres of life.

This intertwined nature calls for both global and regional efforts to resolve it. The Steering Against Superbugs perspective recognizes that “governing AMR surely depends on global coordination and leadership.” But it also notes that the complex nature of the AMR crisis in different parts of the world “calls for polycentric and ‘glocal’ governance approaches, rather than one uniform global approach alone.”

Scientific innovation continues as well. One proposed avenue of solution takes advantage of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance diagnosis and surveillance. This technology is starting to yield results. Generative AI has been used to invent two new potential antibiotics that may be effective against gonorrhea and MRSA. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) team that developed them have suggested that a “second golden age” of antibiotic discovery could be powered by AI. But while the compounds designed atom-by-atom by the AI were successful in killing the superbugs in a lab environment and in testing on animals, these developments remain years away from widespread clinical use.

Beyond AI, researchers continue to work toward new antibiotics; they’re finding novel pathogen inhibitors in soil, developing vaccines for prevention, and engineering bacteriophages (or phages—viruses that selectively infect bacteria) for the treatment of disease-causing bacterial infections.

Other measures are more basic: improving sanitation, water purity and hygiene where needed in the world, and taking steps to prevent the spread of infection in hospitals.

Our Own Worst Enemy

Many of the most impactful measures we could employ are already in our hands (see the list of practical steps below); it’s only a question of us all applying them consistently. To do so would require each of us to act with a real sense of duty regarding our shared citizenship and our stewardship of the world around us.

Zaman describes microbes as “microscopic but mighty life-forms that can just as easily harm the very body in which they reside.” Identifying a superbug under a microscope and doing our utmost to eliminate it is only part of the challenge. Preventing their spread requires addressing our behavior, values, governance and competing interests.

Why do we so often undermine our own advances? We’ve weakened the power of antibiotics through misuse and now struggle to escape the trap we’ve set for ourselves. The pattern reveals itself repeatedly: in short-term thinking that sacrifices future well-being for present convenience, in economic systems that prioritize profit over stewardship, in our inability to consistently act responsibly even when we know the price of doing otherwise.

Scientific progress continues, but technology alone has never been our limitation. The question is whether we can sustain the commitment these solutions require.

Practical Steps to Slow the Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance

The effort to cut back on unnecessary use of antibiotics involves balance. Those who need the drugs for serious bacterial infections require ready access to them. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic use helps prevent the drugs from becoming ineffective in fighting infection.

Organizations such as the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, the US Centers for Disease Control and the UK National Health Service offer a number of practical tips:

- Understand that misuse causes resistance. It is not our bodies that become resistant to the drugs—it is the bacteria themselves that change to resist the antibiotics. What we do affects everyone.

- Take antibiotics only if your medical provider says you need them. They are not effective on viral infections, such as colds or flu. A test can help distinguish between viral and bacterial infections.

- Follow the instructions of medical professionals precisely; take medicine exactly as prescribed for the full time prescribed, even if you start feeling better.

- Don’t save leftover antibiotics for later.

- Don’t share antibiotics with others.

- Prevent infections before they start. This includes proper sanitation, frequent handwashing, access to clean water, staying home when sick to avoid infecting others, and receiving vaccines when appropriate.

- Practice safe food handling and preparation to lower the risk of food poisoning.

- If you have animals to care for, use antibiotics only when needed to treat bacterial infections.

- Tell friends and family about antibiotic resistance to help raise awareness.