There Is Hope for Humanity

Some who study potential global collapse suggest it’s not too late to change the trajectory if we recognize and address the problems now. Others counter that we’re in collective denial and are already past the point of no return. How can we remain hopeful?

I’ve been writing about the problems facing human society for many years. But I have never seen so many others in so many fields warn of impending global catastrophe as I do now. It’s not that these writers are necessarily throwing in the towel; most want to remain optimistic (or feel they have no choice) or believe they have a duty to at least try to solve problems on their own level.

Take Julian Cribb’s How to Fix a Broken Planet (2023), in which the author lays out a plan to solve the top 10 existential problems threatening humanity. He joins others in calling for “an ‘Earth System Treaty’, a legal framework that covers all the risks we presently run and seeks to have humans live within a ‘safe operating space’.” He believes this will require the mobilization of ordinary citizens, as governments are severely limited by procrastination and short-term goals. He says, “Only through these billions of concerned citizens acting together can politics, commerce, religion, and society be induced to adopt wisdom—and make the changes essential to our survival as a civilisation and as a species.”

Yet even this hopeful observer of our condition is cautious about the outcome. He says, “The question is whether humans still have the intelligence and the wisdom to adopt these solutions.”

Despite such an ambitious and laudable plan, the thought persists that we may have passed the point of no return. The problems are multifaceted, interconnected, intensifying, global. The adjectives used to describe them include “critical,” “unprecedented,” “existential,” “irreversible” and “apocalyptic,” along with related terms and phrases such as “permacrisis,” “defining moment,” “tipping point,” “biblical proportions,” “mass extinction,” “heading for disaster” and “systemic collapse.”

What has brought us to this moment? And how can we remain hopeful that humanity will, in fact, survive?

“Every day we face mounting risks from global poisoning, an increasingly violent climate, a shakier food supply, growing scarcity of resources . . . and from the steady unravelling of Earth systems . . . that support life on this planet.”

A Growing Threat

The threat of imminent collapse in so many areas is linked in most cases to the industrialization of civilization that began in the mid-19th century. The large-scale burning of coal and the development of steam power led to the rapid expansion of railway systems and the blossoming of an age of technological invention and automated production, all of which was furthered by the subsequent discovery of oil. The rapid expansion of trade and industry after the Allied victory in 1945 accelerated the world toward its present dilemma.

Today, across-the-board exponential increases have become so familiar that they’re often overlooked. Yet the ever-steeper upward curve signals major change and potential collapse. Nothing can increase exponentially forever.

Because humans are implicated in these exponential patterns, the geological period in which we find ourselves has been named the Anthropocene, defined by “collapsologists” Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens as “a time when humans have become a force that upsets the major biogeochemical cycles of the Earth system” (How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times). The year 1945 looms large, when the first nuclear explosions deposited a global layer of radioactive nuclides.

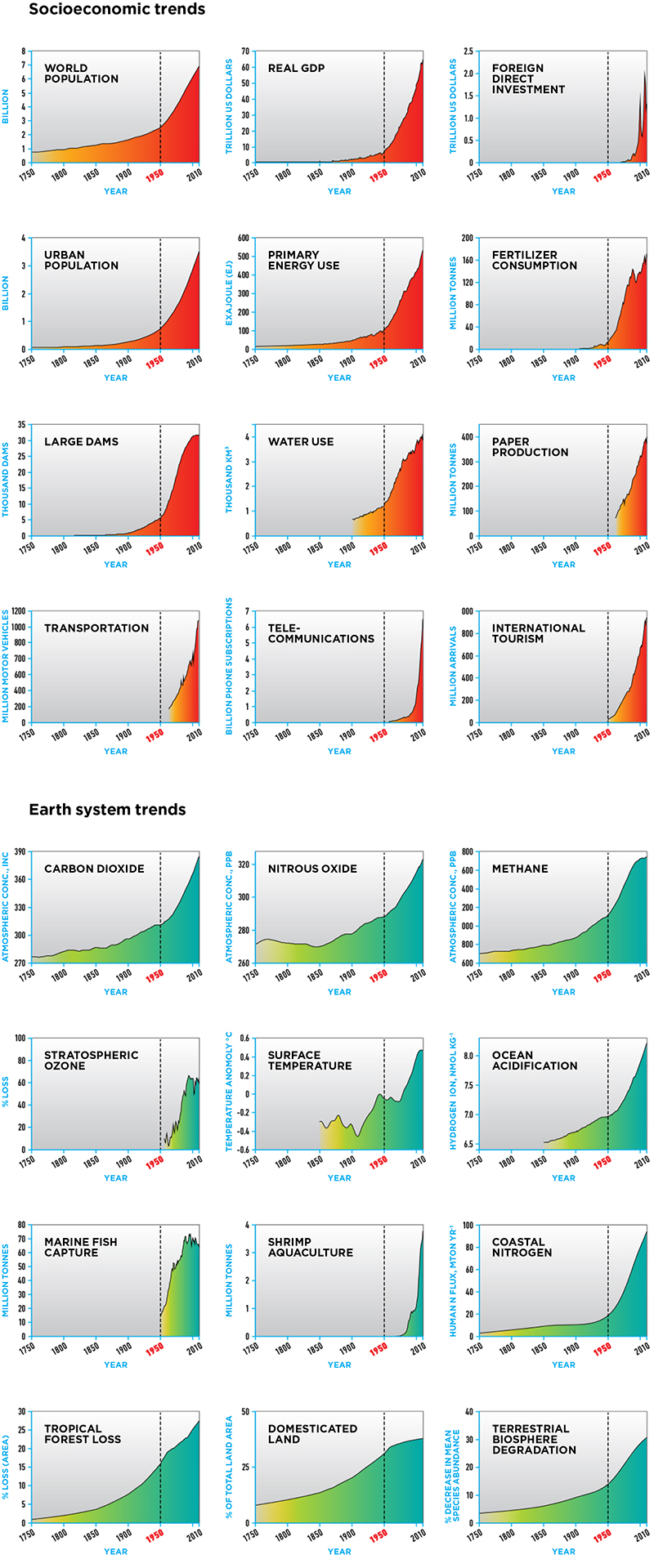

Those who study collapse point to exponential trends across socioeconomic and earth-system measurements. These include pollution, urban population, water and energy consumption, gross domestic product, flooding, deforestation, fertilizer use, species extinction, greenhouse gases, ocean acidification, methane, and land domestication, among other dire indicators.

The Great Acceleration: These graphs chart trends from 1750 to 2010 in global indicators for socioeconomic development (top 12 graphs) and the structure and functioning of Earth systems (bottom 12 graphs). The vertical dotted line running through each graph represents 1950, the point at which many of the numbers begin rising exponentially.

Adapted from “The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration” by Will Steffen, Wendy Broadgate, Lisa Deutsch, Owen Gaffney and Cornelia Ludwig, The Anthropocene Review (2015). Used by permission of the authors.

As former French environment minister Yves Cochet wrote in his postscript to Servigne and Stevens’s book, “we have never had so many indications of the possibility of an imminent global collapse.” And while the book’s authors define their work as “the transdisciplinary study of the collapse of our industrial civilization, and what might succeed it, based on the two cognitive modes of reason and intuition and on recognized scientific studies,” they remain cautiously hopeful. Whether this hope is fully justified, however, remains an open question.

For example, one existential threat that has receded for many is that of nuclear war and the resulting nuclear winter. But the fact that such an eventuality never materialized during the decades of living in the nuclear shadow of the Cold War does not mean that the threat should no longer be considered. Despite other existential risks that threaten our world, the nuclear risk, greatly elevated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, may be the most imminent.

Another 1945 event associated with the beginning of the nuclear age was the formation of a society to warn of the new technology’s dangers. The founders were Albert Einstein and scientists from the University of Chicago who had worked on the Manhattan Project to create the first atomic bomb. In 1947 they came up with the idea of the Doomsday Clock, with its hands nearing 12 o’clock, as a way to publicize the nuclear danger facing the world. The clock was based on the idea of counting down to an apocalyptic “midnight.”

Every year since then, depending on certain other world conditions, the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, in consultation with its board of sponsors (which includes 10 Nobel laureates), has moved the clock forward or back. In 2023, they set it at its closest point to midnight ever—90 seconds from global catastrophe. This was due in part to the war in Ukraine and the heightened nuclear threat that it poses. They now also include in their assessments the impact of other disruptive technologies, as well as climate change, biological threats, and the breakdown of norms and institutions.

“Whereas industrialism’s essential aim has been to bring the natural world under human supervision, in practice the effect has been to leave it less controllable.”

Their current assessment is supported by the 2022 report from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). While it showed that most of the recent increase in global military spending was for conventional weapons, it noted alarmingly that “the nine states that possess nuclear weapons were all engaged in upgrading their nuclear arsenals.”

A bipartisan report to the US Congress in October 2023 expressed further concerns. It noted that both Russia and China will soon become nuclear peers with the United States, a risk that it said must be addressed now. Reflecting on recent changes in geopolitical reality since the last congressional report, the authors commented: “The vision of a world without nuclear weapons, aspirational even in 2009, is more improbable now than ever. The new global environment is fundamentally different than anything experienced in the past, even in the darkest days of the Cold War.” Accordingly the commission recommended, in part, the “replacement of all U.S. nuclear delivery systems, [and the] modernization of their warheads.”

“The Five Stages of Collapse”

Dmitry Orlov is a Russian-American engineer and writer. Having witnessed the late-20th-century collapse of the Soviet Union, he went on to outline what he calls “the five stages of collapse.” In his 2013 book by that title, Orlov presents his case for “the imminent collapse of global industrial civilization.”

Following are the five stages he identifies, along with his description of each:

Stage 1: Financial collapse. Faith in “business as usual” is lost. The future is no longer assumed to resemble the past in any way that allows risk to be assessed and financial assets to be guaranteed. Financial institutions become insolvent; savings are wiped out and access to capital is lost.

Stage 2: Commercial collapse. Faith that “the market shall provide” is lost. Money is devalued and/or becomes scarce, commodities are hoarded, import and retail chains break down and widespread shortages of survival necessities become the norm.

Stage 3: Political collapse. Faith that “the government will take care of you” is lost. As official attempts to mitigate widespread loss of access to commercial sources or survival necessities fail to make a difference, the political establishment loses legitimacy and relevance.

Stage 4: Social collapse. Faith that “your people will take care of you” is lost, as local social institutions, be they charities or other groups that rush in to fill the power vacuum, run out of resources or fail through internal conflict.

Stage 5: Cultural collapse: Faith in the goodness of humanity is lost. People lose their capacity for “kindness, generosity, consideration, affection, honesty, hospitality, compassion, charity.” Families disband and compete as individuals for scarce resources. The new motto becomes “May you die today so that I can die tomorrow.”

Another Approach

Similar to the reluctance of some to accept nuclear war as a present threat despite these warnings, there is an unwillingness to consider religious or biblical references to “last days” beyond their use as metaphor, or in a secularized way. Some even reject this approach altogether. Servigne and Stevens write, “We will not be dealing with millenarian eschatology.” That’s to say, they reject utopian concepts of a world beyond “the end times.”

More charitably, Wes Jackson (cofounder of the Land Institute) and his colleague Robert Jensen say they “will embrace a version of the apocalyptic from the Christian tradition, with our own spin, of course.” They put faith in those who will choose to make a difference in the face of impending collapse, whom they describe—using biblical language, though without theological implications—as “‘a saving remnant,’ the human population that would endure on the other side of the collapse.”

I want to comment on both these approaches to show that there is an often-overlooked way in which end-time studies are directly relevant to the study of collapse. I’m not talking in fundamentalist terms or a narrow sectarian way. But I want to make it clear that in biblical terms there is a literal, spin-free end time that speaks to human power gone awry, to cascading crises of human origin, and to hope for humanity.

Before we get to that, it’s important to recognize an important facet of our psychology—one that stands in the way of change. When Cochet asks whether we can muster the will to make the necessary changes in time, he suggests that our social psychology is against us. Servigne and Stevens likewise note that “uninhibited collective denial . . . is such a prominent feature of our times.”

Without recognition of the problems and a willingness to change, we will allow denial to overcome personal responsibility. We will not act in our own best interests unless we perceive that others are also acting. That is, most of us will not go it alone—stand up and be counted—unless we recognize that by refusing to do so, we have become our own worst enemies. The calculation is that it is not worth the effort, or perhaps the social isolation, if we are not sure that others will act in unison with us.

But Cochet goes further. He raises our inaction in the face of impending collapse as a moral dilemma: “Collapsology, by its very object, leads to the distinction between good and evil, with good being any action that will reduce the number of deaths, and evil being indifference to this criterion or, worse, morbid pleasure at a larger number of deaths. In this sense, I can pass a judgment of moral responsibility on myself and on others.”

“In media and intellectual circles, the question of collapse is not taken seriously.”

This call to responsibility is what so many avoid. But it is what is needed to begin to restore human life.

The premier apocalyptic work is surely the first-century biblical book Revelation (Greek: apokalypsis, “unveiling”). Twenty centuries later, what it has to say about the world in “the end time” is strangely familiar, both in terms of human power and pride in material achievement and in terms of the destruction of the earth. It describes a globalized human society in an incredibly destructive mode, so much so that God announces the time has come to “destroy those who destroy the earth”—those who plunder its resources and ruin the earth (Revelation 11:18). Even God cannot solve the problem without bringing an end to those who persistently refuse to follow the path that leads to peace and equity for all.

Their system’s predatory and violent attitude extends to a long list of the world’s tradable goods and luxuries. These include food and drink, precious metals, exotic furnishings, precious stones, fabrics, perfumes, weapons, and, most disturbingly, the exploitation of the “bodies and souls [minds] of men [people]” (Revelation 18:11–13). In this account we’re dealing with a world that cannot be saved unless the system is overcome. Its political powers, international merchants, shipping companies and global magnates show no inclination to change their self-serving and corrupt allegiances and are heartbroken when the system suddenly and completely falls (verses 9–10, 15–19).

“Let’s admit it: we’re facing some serious problems to do with the environment, energy, climate change, geopolitics, and social and economic issues, problems that are now at a point of no return.”

So where is the hope?

Revelation describes a system that has run out of time, its proponents unwilling to change. The book declares that our only hope lies in God’s intervention to prevent self-destruction and human annihilation, and in the remnant few who have committed to an entirely different path. In a passage referring to a great crisis at the end of this present age, Jesus is quoted as saying it will be a time like no other—a time when all human life could be extinguished (nuclear weapons have already made this possible). Yet a remnant will be saved alive: “If those days had not been cut short, no one would be saved. But for the sake of the elect those days will be cut short” (Matthew 24:22, New English Translation). Only God can do this, and an elect (or saved and saving) remnant will play a role in the transition to a new world.

How do we choose between good and evil? How do we accept the challenge to practice moral responsibility now? How do we become part of a humble saving remnant? It requires a complete change in approach. It’s about a new identity, about asking and answering the questions Who am I? And who am I supposed to be? It’s about discovering the God who rescues. In this way, there is hope.