Child Soldiers

When you think of war, what images come to mind? Perhaps you see rows of uniformed soldiers marching in step, or tanks and armored vehicles traveling in convoy, or the U.S. military’s televised “Shock and Awe” precision bombings over Iraq. The reality, however, is that the majority of wars today are intrastate conflicts fought with small arms. And the disturbing news, as reported in the “Child Soldiers Global Report 2008,” is that wherever such conflicts take place, many of those fighting are children. Yet how often, when you think of war, do you picture a child brandishing an AK-47 assault rifle or a rocket-powered grenade launcher?

At least one such child’s story has become widely known: A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier provides the moving firsthand account of Ishmael Beah’s experiences as a child soldier in Sierra Leone. Separated from his family when their village was attacked by rebel forces, Beah for a while avoided abduction into the armed conflict that enveloped his country. Eventually, however, hunger and insecurity led him to join the government forces, who compelled him not only to fight against the rebel opposition but to perpetrate acts of extreme violence against innocent civilians along the way.

“Most evidence suggests that ordinary children, faced with the extraordinary circumstances of combat, are capable of learning to kill and to kill repeatedly.”

While Beah’s story is shocking, it is certainly not unique. He was just one of an estimated 250,000 boys and girls (according to current UN estimates) taking part in wars around the world at any given time over the last two decades. His book has increased awareness of the plight of children who are prematurely exposed to the harshest and most brutal experiences imaginable, including murder, mutilation and rape.

What Is a Child?

While the definition of childhood varies from culture to culture, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child defines “child” broadly as “every human being below the age of 18 years.” The 2007 Paris Principles interpret “a child associated with an armed force or armed group” as “any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys, and girls used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities.”

“Child soldiers. Two simple words. But they describe a world of atrocities committed against children and sometimes by children.”

Most child soldiers are between the ages of 13 and 18, though many groups include children aged 12 and under. Beah, for example, fought alongside a 7-year-old and an 11-year-old. The latter was mortally wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade, Beah recalls, and as the small boy lay dying in front of him, “he cried for his mother in the most painfully piercing voice that I had ever heard.”

A May 2006 Africa Research Bulletin reported that “in states such as Angola, Burundi, Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Sudan and Uganda, children, some no more than seven or eight years of age, are recruited by government armed forces almost as a matter of course,” while rebel forces in Sierra Leone were known to recruit children as young as five.

According to the “Child Soldiers Global Report 2008” (produced by the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers), 21 countries or territories around the globe had children engaged in conflicts between 2004 and 2007. Today there are child soldiers in many nations around the world, including the Central African Republic, Chad, Somalia, Uganda, Myanmar (Burma) Sudan, Iraq, Colombia and Sri Lanka. Both government and non-state forces in developed and developing countries are culpable. Developing countries embroiled in intrastate conflicts tend to use younger children in their desperation, but even the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Canada and New Zealand recruit youths as young as 17.

Girls not only fight on the front lines but provide domestic labor and serve as “wives.” From the age of 13 they may be given to boy soldiers or adult commanders. They have no choice: those who refuse are killed or raped. Of course, many of them soon become mothers who must take on the added responsibility of providing food for their children. It’s a grueling existence, and malnourishment, exhaustion and mistreatment take a high toll.

It’s no wonder, then, that many of their babies don’t survive. Some don’t even survive birth itself. In “Child Soldiers: What About the Girls?” University of Montana researcher Dyan Mazurana and University of Wyoming professor Susan McKay assert that “the RUF’s [Revolutionary United Front’s] birthing practices in Sierra Leone included jumping on the abdomens of expectant girls and inserting objects into their vaginas to force the girls into labor well before they were properly dilated, or tying their legs together to delay birth if the forces needed to move quickly.”

In addition to pregnancy and motherhood, repeated sexual assault can also lead to infection, disease (including HIV/AIDS), uterine deformation, vaginal sores, menstrual complications, sterility and death, as well as to “shock, loss of dignity, shame, low self-esteem, poor concentration and memory, persistent nightmares, depression, and other post-traumatic stress effects.” Mazurana and McKay stress the importance of treating these young women: “Because girls are the mothers and caregivers for future generations, their health has a critical impact on the overall health of a nation and its population.”

A Ready Commodity

According to an Amnesty International report, “both governments and armed groups use children because they are easier to condition into fearless killing and unthinking obedience” (“Hidden Scandal, Secret Shame: Torture and Ill-Treatment of Children,” 2000). Children are a cheap and plentiful resource for military commanders in need of a steady troop supply to war zones. Their underdeveloped ability to assess danger means they are often willing to take risks and difficult assignments that adults or older teenagers will refuse. Children are more impressionable than adults, and depending on their age and background, their value systems and consciences are not yet fully developed.

While children become involved with armed groups in a variety of ways, child-soldier expert Michael Wessells told Vision that no choice is a “free choice” because it is typically grounded in dire circumstances, including poverty, starvation, separation from their families, physical or sexual abuse, or lack of livelihood or education. China Keitetsi, whose book Child Soldier relates her own story of life in an armed group, joined because of a difficult home situation. It’s true that some children decide to enter conflicts voluntarily because they relate to the group’s ideology, as in Palestine and Sri Lanka; but most feel they simply have no choice.

“The rebels first abducted my brother in 1997. He has never come back. . . . This year, one of my elder brothers and two younger sisters were also abducted, on the same night. None of them has returned.”

The most distressing method of recruitment is without a doubt kidnapping. The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda has the worst record of abduction, stealing tens of thousands of children over the past decade alone. This has created the “night commuters” phenomenon, portrayed in the stirring picture book “When the Sun Sets, We Start to Worry. . .”: An Account of Life in Northern Uganda. Its foreword states, “Each night in northern Uganda, more than 40,000 mothers, grandmothers and children leave their homes and travel many miles on foot to the main towns, seeking refuge from abduction by the LRA.” In town they will sleep outside hospitals, churches and other public buildings. Seventy-year-old Elijah tells of his experience: “At night, my eight grandchildren sleep in the bush with no blankets. I don’t know where they sleep, and they always choose a different spot. Not even your mother is supposed to know your hiding place. Rebels always force parents to show them where the children are hiding.”

UNICEF reports that the LRA has abducted children as young as 5 but mostly between the ages of 8 and 16, often after killing their parents in front of them. The young “recruits” are then forced to march to southern Sudan. Those who can’t carry their loads or keep pace with the others are killed. Those who attempt escape are severely punished. Girls are routinely raped.

Ugandans may be at highest risk of abduction, but children in other nations have plenty to fear as well. In Bhutan, Burundi, Myanmar, El Salvador, Ethiopia and Mozambique, says Wessells, children have even been kidnapped while at school. And the “Child Soldiers Report 2008” notes that the same is true in Bangladesh and Pakistan. Warlords in Afghanistan and Angola’s UNITA have employed a quota system in which they demand that villages each hand over a certain number of youths. Those villages that don’t oblige are attacked.

Turning Kids Into Killers

Military commanders use proven tactics to produce unquestioning obedience in these homesick children while transforming them into killers. New recruits are often forced to kill or perpetrate various acts of violence against others, including strangers, escapees or even members of their own village or family. Coercing the children to harm or kill people they know has the added benefit of discouraging them from attempting escape, as they know they will no longer be welcome back home.

Some groups also practice cannibalism, making young recruits drink the blood or eat the flesh of their victims. While recruits are often told “It will make you stronger,” Wessells argues that the real motivation is to “force children to quiet their emotional reactions to seeing people killed and demolish their sense of the sanctity of life and their tendency to show respect for the dead.”

In addition, drugs are administered to deaden the effects of conscience: amphetamines, crack cocaine, palm wine, brown-brown (cocaine mixed with gun powder), marijuana and tranquilizers help disengage the child’s actions from any sense of reality. Children who refuse to take the drugs are beaten or killed, according to Amnesty International. One rehabilitation camp director told Wessells that recruits “would do just about anything that was ordered” when they were on drugs.

Revenge is also used as a motivator. Ishmael Beah’s commanders told him to “visualize the enemy, the rebels who killed your parents, your family, and those who are responsible for everything that has happened to you.”

While these tactics are very successful, the violence will still affect young consciences. “Initially most children experience a mixture of disgust, guilt and self-contempt,” writes Wessells. “These normal reactions reflect the strength of children’s deeply held civilian morals and social commitments not to murder or to hurt friends. Faced with the magnitude of their actions, children may also rationalize their actions by telling themselves, ‘I didn’t want to do it. I had to follow orders or I would be killed.’ . . . Other children may see such acts as surreal, as if they occurred in a dream world, and they may feel quite split off or dissociated from them. This splitting process is a normal self-protective reaction to the strain induced by the enormous gap between children’s previous morals and the atrocity they have been forced to commit. . . . The children’s former values might not be lost so much as suspended.”

Learning Peace

Children who are rescued from combat, or who survive until the conflict’s conclusion, face an enormous challenge in trying to return to normal civilian life.

In the past, while immediate physical needs would often be met (food, water, shelter, security, family reunification), former child soldiers had difficulty processing their experiences and reintegrating within their communities. Many were stigmatized as rebels and failed to make the transition. Aid organizations and international governmental organizations such as UNICEF now recognize that children who have been soldiers need more than physical help. They need healing from emotional difficulties and traumatic experiences, protection from re-recruitment, training and education in peaceful roles, and a careful reintroduction into their communities. As a result, DDR (disarmament, demobilization and reintegration) provisions are now included in peace accords. These clauses are specifically intended to help facilitate victims’ successful return to society without fear of stigmatism and rejection.

The rehabilitation process includes drug withdrawal and psychological adjustment but also recovery from posttraumatic stress disorder, the symptoms of which include nightmares, flashbacks, aggressiveness, hopelessness, guilt, anxiety, fear and social isolation. NGO programs include games and activities that emphasize trust-building and opportunities to practice nonviolent conflict resolution. Drawing, storytelling, music and drama are often used as ways for the children to communicate and process their experiences.

According to Christian Children’s Fund, a leading nonprofit organization involved in psychosocial interventions including the rehabilitation of former child soldiers, it can take as long as three years to be reintegrated into society. Beah spent eight months in a rehab facility before being placed with an uncle. It took him two months just to withdraw from the drugs, and several months passed before he could sleep at night without medication. It took even longer for him to recall early childhood memories as he grappled with flashbacks of his war experiences. As he gradually learned to trust adults again, he marveled at the workers’ patience and their refusal to give up on their hardened and antagonistic charges. Beah recalls that his nurse Esther looked at him with the “inviting eyes and welcoming smile that said I was a child.” After being stabbed, beaten or otherwise mistreated by the children, the staff would tell them, “None of these things are your fault.” It annoyed him at first, but he eventually came to believe it. He writes, “It lightened my burdensome memories and gave me strength to think about things.”

While they have not always succeeded the first time, NGOs involved in these rehabilitation programs have gained a wealth of experience following the recent conclusions to some long-running African conflicts. The UNICEF-initiated Paris Principles have attempted to capture this knowledge, providing guidelines for effective disarmament, demobilization and reintegration. Sixty-six governments have endorsed the principles and “have pledged to work for the release of all child soldiers from fighting forces, and to support programs which genuinely address the complex needs of returning child soldiers.” As a result, children are successfully being returned to communities equipped with the tools needed for the often difficult transition back to a peaceful civilian life.

Beah has traveled the world speaking to audiences about the resilience of child soldiers. He tells them, “We can be rehabilitated,” and then adds, “I believe children have the resilience to outlive their sufferings, if given a chance.” While at one time it was assumed that these youths were damaged goods, it is now more widely accepted that former child combatants, given the proper help and support from these special aid workers and others, can be reintegrated successfully into society.

Where There’s War . . .

With the good work being done for former child soldiers, is it possible to foresee a time when children will no longer be sent into battle? The answer seems to lie in the phenomenon of war itself. The “Child Soldiers Global Report 2008” proclaims that “despite the best efforts of UN agencies, NGOs and others, large-scale releases of children from armed forces or groups have rarely taken place before hostilities end. . . . Indeed, where armed conflict does exist, child soldiers will almost certainly be involved.” The same report adds, “Reality dictates that an end to conflict will produce the most concrete results.”

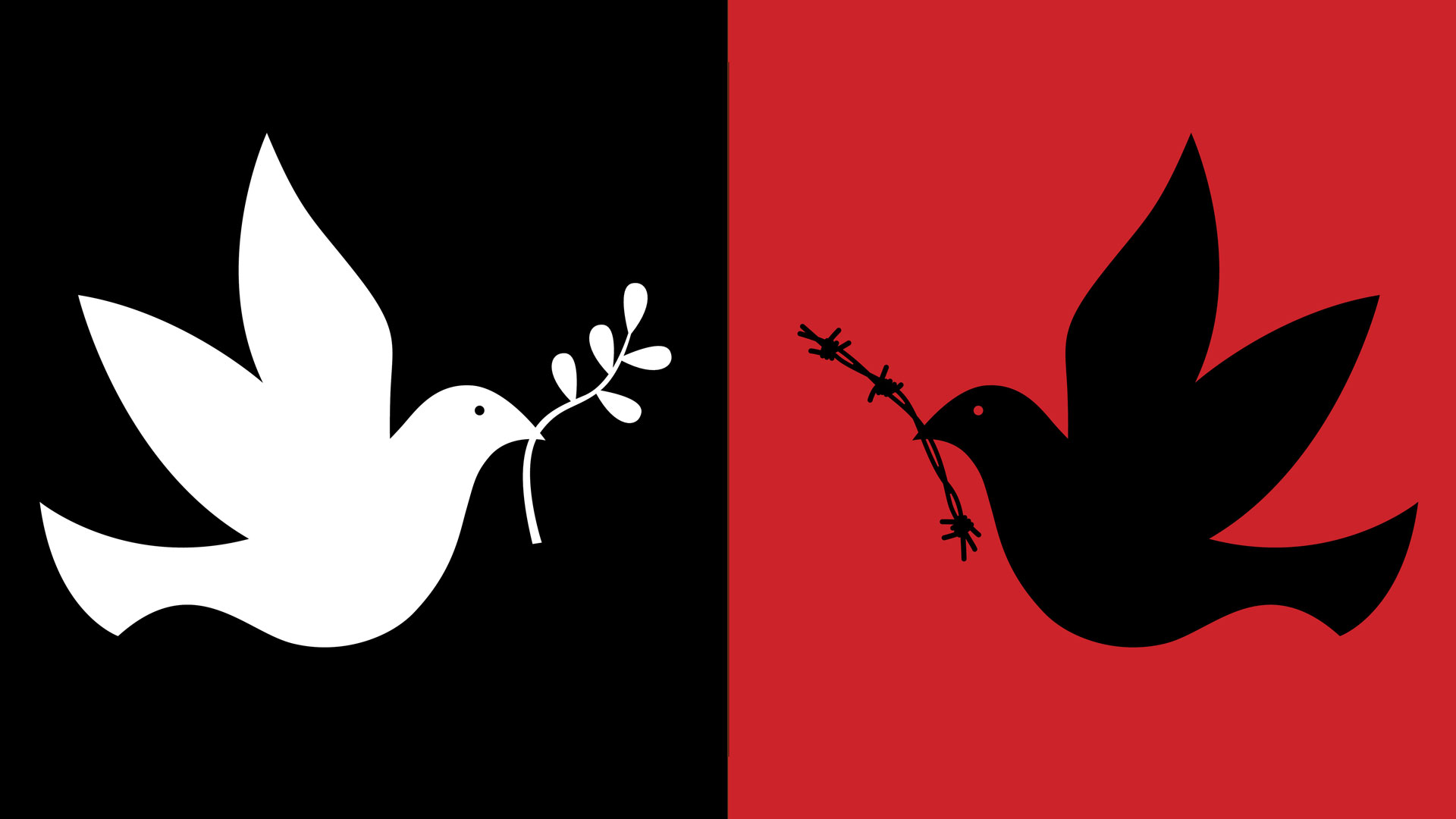

This perspective suggests that the only way to rid the world of child soldiering is to rid the world of war. But history provides little encouragement that this is possible. The Bible nevertheless makes exactly the same connection between the safety and well-being of children and an end to conflict. Contained within its pages are many passages that describe a time yet future—a time when boys and girls will play in the streets, free of the abuses and the fear with which so many of them live today. It seems that this source of ancient Hebrew wisdom and the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers both indicate that without an end to war there will be no end to child soldiering. What the Bible offers that others can’t, however, is hope that such a conclusion will someday be achieved.