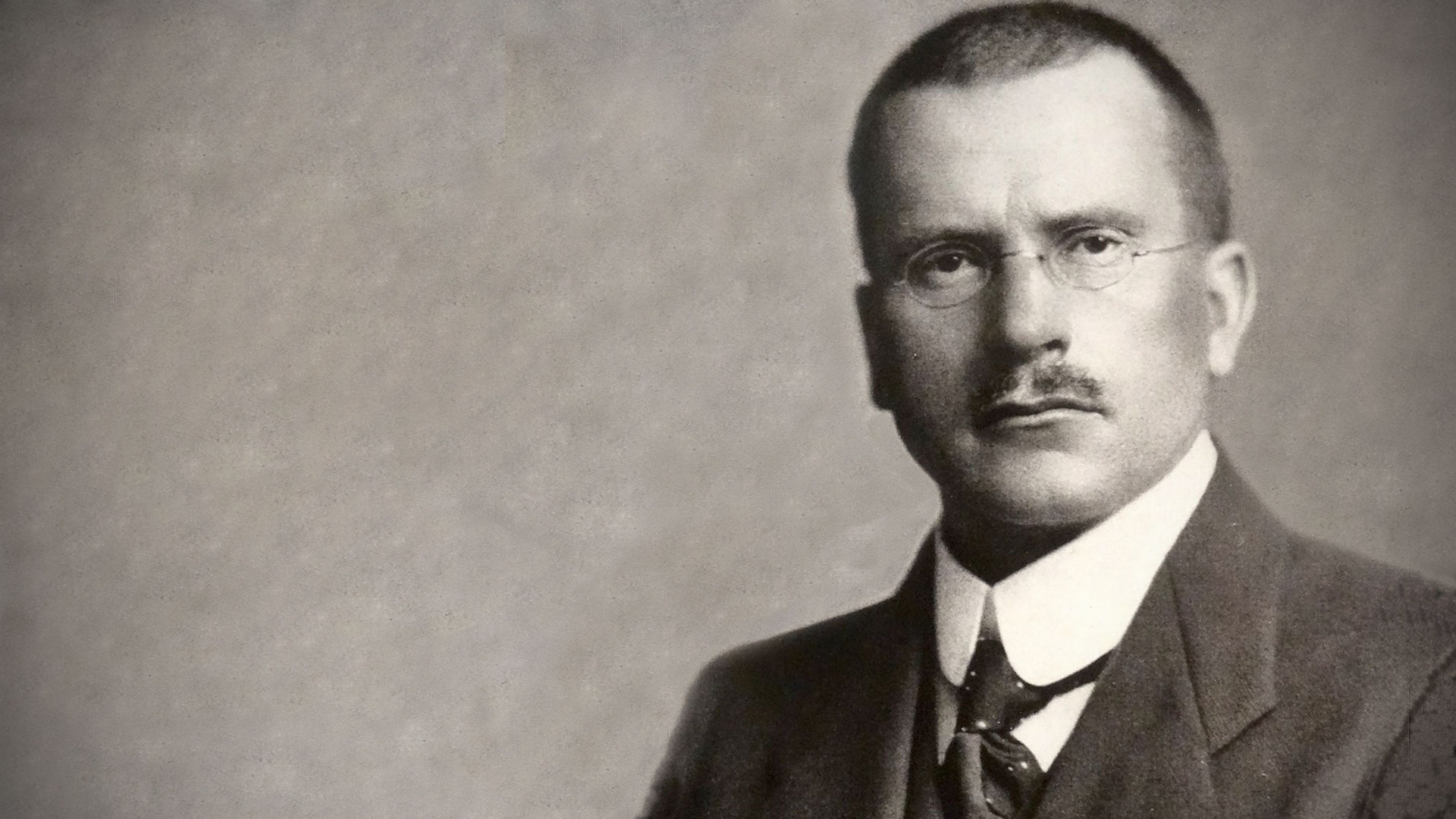

Carl Jung: Psychologist or Mystic?

Carl Gustav Jung is best known as one of the fathers of modern psychotherapy alongside his erstwhile associates Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler. He introduced such terms as introversion and extraversion, the collective unconscious, archetypes and synchronicity into the popular vocabulary. But beyond that, most people today probably know little about the man. Understanding something of his profound influence, however, is critical for anyone who wants to better understand the current state of Western culture.

After his departure from Freud’s Vienna Psychoanalytic Society in 1910, Jung founded an approach he named Analytical Psychology, many tenets of which have not only led some to refer to him as a “founding father of the New Age” but also prevented much of the scientific community from taking him seriously.

Stung by his lack of acceptance as a scientist, Jung hated being called a mystic, a label which nevertheless clung to him throughout his life and beyond. Even his secretary, Aniela Jaffé, acknowledged that “the clear analogies that exist between mysticism and Jungian psychology cannot be overlooked,” although she insisted that “this fact in no way denies its scientific basis.”

Likewise Gary Lachman notes in his 2010 biography that despite Jung’s assertion to the contrary, “he would, by his own definition, be a mystic.” He openly admitted to having paranormal experiences and participating in séances. Lachman also attributes the psychologist’s reputation as a mystic to the fact that he claimed special, secret knowledge or gnosis “not obtained through the normal methods of cognition.” In fact, “Jung’s link to Gnosticism was so significant,” observes Lachman, “that one of the Gnostic scrolls making up the [Nag Hammadi] library was purchased by the Jung Foundation in 1952 and named the ‘Jung Codex’ in honor of the man many saw as a modern Gnostic.”

“Recollection of the outward events of my life has largely faded or disappeared. But my encounters with the ‘other’ reality, my bouts with the unconscious, are indelibly engraved upon my memory.”

Jung’s use of religious terms has sometimes encouraged the misconception that his idea of spirituality is somehow compatible with a biblical view; but in Jung’s writings, the subjects of God, Christ and religion in general were invariably presented as mythology.

So who was this ambitious loner? Most biographies focus on the relational history of their subjects—the families into which they are born and the later encounters that influenced their development, but a sketch of Carl Gustav Jung’s life, by necessity, is bound to have a slightly different focus. The experiences that had the most profound effect on him were, by his own account, those that occurred within himself; people and the physical trappings of everyday life were relatively uninteresting to him.

“The very things that make up a sensible biography,” said Jung in the autobiography he dictated to Jaffé, had become for him mere “phantasms” compared to one’s inner developments. These consisted of his experiences in the form of dreams, visions (some might characterize them as hallucinations), interplay between his two inner “selves” (one of which, dubbed “No. 2,” he described as an authoritative 18th-century character with a white wig, who traveled in a coach and wore buckled shoes), and other active imaginings that formed inner pathways to what he would later term “individuation,” or the process of becoming who we are by integrating the conscious with the unconscious.

Nevertheless some aspects of a sensible biography of Jung can be collected and narrated. His birth on July 26, 1875, for instance, was certainly no phantasm, at least so far as his mother, Emilie Preiswerk Jung, must have been concerned. Carl was her fourth child, but two daughters had been stillborn and another son had died soon after birth. The children’s father, Paul, was a Protestant minister, but he was unhappy both in his profession and in his marriage, which could not have been pleasant for his wife either. Described as depressed, and more interested in the occult than in showing any affection to her son, Emilie had to be hospitalized for a period after suffering a breakdown when Carl was about three, an event that made a lasting impression on him. Jung records that he was never able to trust women again.

He grew up essentially an only child, and the arrival of his sister Gertrude when he was 9 changed little. Jung says, “I played alone, and in my own way. Unfortunately I cannot remember what I played; I recall only that I did not want to be disturbed.” Lachman observes that this preference for isolation “stayed with Jung throughout his life.” Albert Oeri, a lifelong friend, remarked retrospectively that he and Jung were initially brought together to play because their fathers were “old school friends” and both men hoped their sons would also form a close relationship. This hope was at first dashed, however; Carl continued to concentrate on his solitary pursuit, refusing to notice Albert. “How is it that after some fifty-five years I remember this meeting at all?” Oeri mused. “Probably because I had never come across such an asocial monster before.”

Even after his marriage to Emma Rauschenbach and his ensuing fatherhood, Jung retained his general disinterest in others. In A Life of Jung, Ronald Hayman notes that while Jung sometimes went sailing with his son Franz (perhaps more out of a love of sailing than out of any particular interest in his son), he generally kept his daughters at arm’s length. On one rare occasion when he included them on a boat trip, he bought them a treat. “Look,” exclaimed eight-year-old Marianne to her mother, “Franz’s father bought me a little cake!” Emma took advantage of the occasion to explain to her daughter that Jung was her father too.

Jung’s wife and five children learned to accustom themselves to the wide range of his eccentricities. In addition to being required to accept one of his mistresses as a member of the household, they also lived with the paranormal phenomena which seemed to increase in the household when Jung would shut himself away in privacy to practice “active imagination”—inducing a state somewhere between waking and sleeping (hypnagogia), in which he would commune with his inner voices in order to resolve any conflicts between the conscious and the unconscious. Jung’s autobiographical descriptions of the visions he experienced in this state might come across as somewhat bizarre to many readers, particularly considering the fact that his ambition was to be seen as a man of science.

“It seems to me as if that alienation which so long separated me from the world has become transferred into my own inner world, and has revealed to me an unexpected unfamiliarity with myself.”

However, his apparent affinity with the spirit world had a long and even familial history. His mother was the daughter of a Hebrew scholar who maintained a chair in his study for the convenience of his dead first wife’s ghost. He was visited by other figures as well, and it was Emilie’s job to shoo them away so he could work on his sermons. Eventually Emilie herself developed “mediumistic powers,” including a second personality who was observed regularly by young Carl in the years leading up to the apparent emergence of his own “No. 2.” Jung records that between his eighth and eleventh year, “the nocturnal atmosphere” at home “had begun to thicken.” Describing the events as “incomprehensible and alarming,” Jung says: “From the door to my mother’s room came frightening influences. At night Mother was strange and mysterious. One night I saw coming from her door a faintly luminous, indefinite figure whose head detached itself from the neck and floated along in front of it, in the air, like a little moon. Immediately another head was produced and again detached itself. This process was repeated six or seven times.”

Considering such experiences together with Jung’s subsequent interests and practices throughout his life—including his clearly Gnostic late-life work, Answer to Job (1952)—one assertion Lachman records him as having made in a 1957 interview seems extraordinary. On that occasion Jung declared, “Everyone who says that I am a mystic is just an idiot.”

But then, by his own estimation, Jung was not the best one to summarize his life. “I am incapable of determining ultimate worth or worthlessness,” his autobiography records; “I have no judgment about myself and my life. There is nothing I am quite sure about. I have no definite convictions—not about anything, really. I know only that I was born and exist, and it seems to me that I have been carried along.” Despite his uncertainty on this issue, Jung nevertheless expressed his conviction of some kind of continuity of being, whether through reincarnation or something else. Many of the concepts he coined for his particular philosophy, at any rate, do seem destined to remain a part of the popular vocabulary.