Bullying: What Parents Need to Know

Dieter Wolke is professor of developmental psychology and individual differences at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom. He is the principal investigator of the precursors and consequences of peer bullying; the goal of his research is to understand why and how some children develop psychological problems while others are more resilient to adverse influences.

In the last 25 years, Wolke and his colleagues have investigated a variety of risk factors for mental and behavioral disorders. They are now exploring bullying across the lifespan—from prenatal precursors to long-range effects—as perpetrators, victims, and victims who in turn bully others reach adulthood.

In this interview, Gina Stepp asks about some of his team’s most recent findings, and about the role parents can play in preventing the problem.

GSOne of the reasons adults often give for not intervening when their children are bullied is that the children need to experience some of that conflict so they’ll know what real life is like.

DW It’s very important to make a difference between bullying and conflict. Bullying is done with the intention of doing harm; it’s done repeatedly, and it’s usually done to someone who is weaker or thinks that they’re weaker. Now, if we have a conflict—a difference of opinion in a discussion—and we are of the same strength, we don’t necessarily want to harm each other or get a power relationship going. And that happens between children, but it also happens with parents. For example, fathers often play-fight with children, and parents can use this to train children to recognize where the limits are. When things get too rough, you say, “This is enough, time out; this is as far as you can go and no further.” Parents can also allow children to manage conflict with one another; but before they hit a brick over the head of another person or become nasty, they have to stop.

GS So what you’re saying is that there is a time to intervene; a certain amount of conflict is all right, but you teach children how to manage the conflict and how to resolve issues.

DW Exactly; and to set limits is very important, because all children need to be socialized, to understand that you can’t take everything you want, and this is not all yours. It’s not like they’re born to know all the social rules.

GS And at different ages they develop different capacities to understand social rules. For instance, until they develop “theory of mind”—the ability to recognize that other children often have preferences and feelings that are different from theirs—they may not be able to grasp the finer points of some social rules.

DW That’s right, but these social skills can be used for good or for bad, because it also makes you more effective as a bully—spreading rumors, excluding someone. Having theory of mind, you know how to hurt without actually physically attacking them.

GS What are some of the effects of bullying?

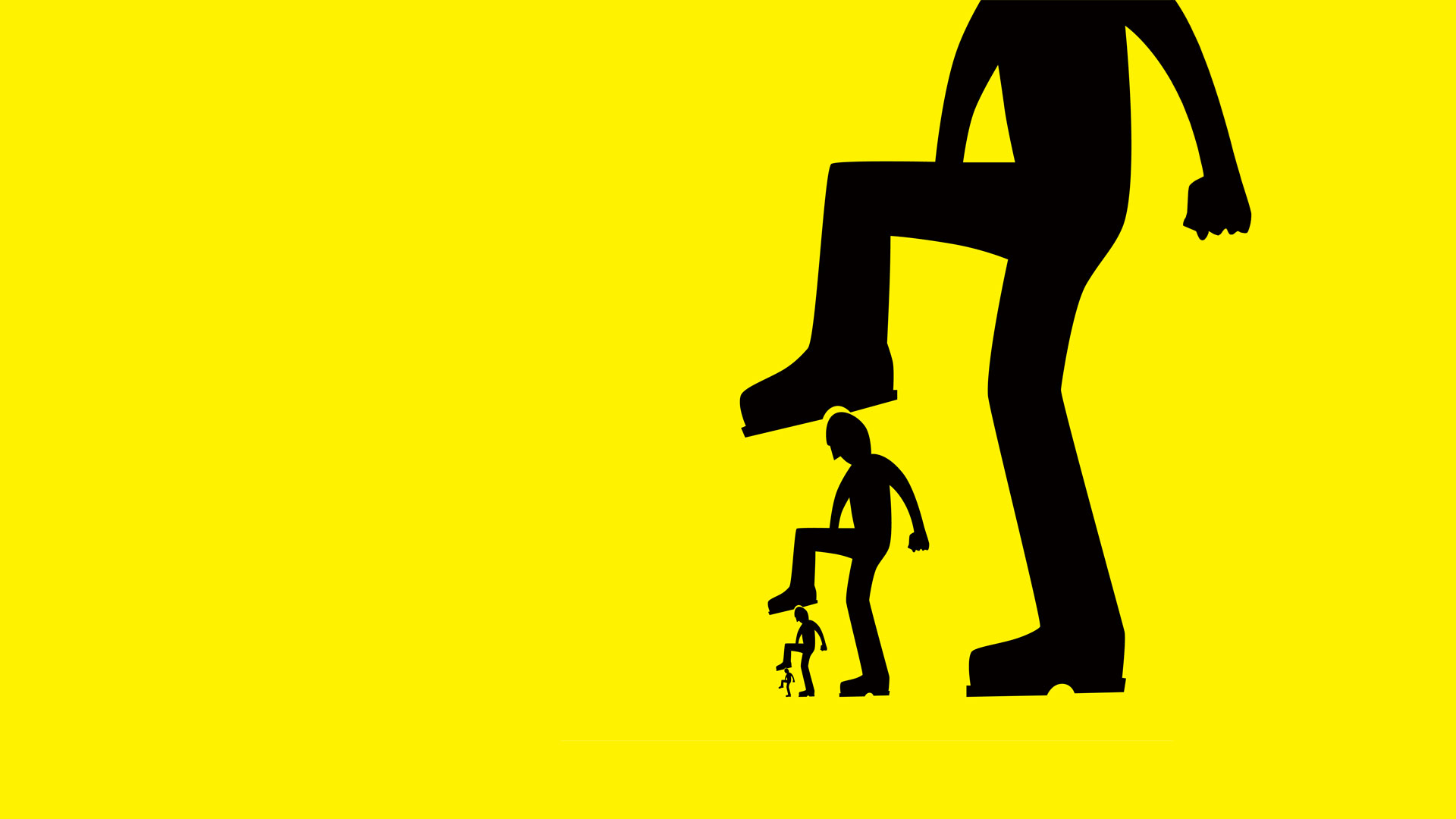

DW One finding from a study we did with researchers at Duke University is that there is an increased risk of depression and anxiety, and also of self-harm and suicide attempts. Another is that victims and bully-victims (those who both are bullied and in turn bully others) are not doing that well economically. They find it more difficult to hold down jobs by 26 years of age. They often leave jobs because they don’t trust, or they feel easily criticized; they leave jobs before they’ve found another job, and they show poorer saving behavior. So there are real economic consequences that make it more difficult to function in the work setting where you have to interact with other people.

Regarding self-harm, we found up to four times increased risk of self-harming in those who are victimized, even if it was just in primary or elementary school. Health professionals and others don’t always ask about a child’s relationships with peers; they forget how important those relationships are. But by the time they are 18, children will have spent much more time with their peers than with their parents.

GS Teenagers still care about what their parents think, but the peer influence is huge.

DW Well, how many children do you know who dress like their parents, who like their parents’ music and go to the same concerts? It’s very few, because we do listen to our peers and it’s very important while we’re growing up that we fit in. To be socially excluded is very hard. I think that mental health and primary health professionals need to remember to ask about peer relationships, because some of the problems, like coming home with a headache, not wanting to go to school, having stomach aches, etc., may be signs not only of an illness or parenting problems, but may be related to wanting to avoid these situations with peers.

GS A new aspect of bullying that we parents didn’t have to deal with as kids is cyberbullying. Once we were home, we were pretty safe unless our sibling was a bully—which is another consideration. But now our kids are still connected to their peers when they get home.

“Cyberbullying . . . allows victims to get revenge. Physically you might not fight back, or you may not have the words, but you can do it anonymously toward someone else.”

DW That’s true. Cyberbullying is important, but we need to be careful not to blow it out of proportion, because 90 percent of those who are cyberbullied are also bullied face-to-face. For example, if you’re sitting in Los Angeles, you wouldn’t go on an electronic device and start bullying someone in China, because a bully wants to see the reaction; it’s about power differential. So they may use another tool in the armory, but they’ll usually use it against someone they know who is in the same class or same school, and they will want to make sure that other people see it as well, or see the reaction to it. Otherwise it doesn’t have any purpose.

GS You don’t get the satisfaction of seeing the effects of your bullying.

DW Exactly. But there’s one important difference with cyberbullying in that it actually allows victims to get revenge. Physically you might not fight back, or you may not have the words, but you can do it anonymously toward someone else.

Still, it’s terrible. I know one child attempted suicide because someone filmed him on the telephone being a rock star with his toothbrush in the bathroom, and when you’re 12 it’s so humiliating to show this to the world. It became a hit; millions looked at it. And it doesn’t go away, so everywhere you walk you will be recognized, and your reputation is destroyed. So I’m not saying cyberbullying isn’t terrible; it’s just another weapon in the armory.

GS Is there something parents can do to reduce the effectiveness of that tool in the hands of the bullies?

DW What doesn’t work nowadays is to take away a mobile phone. Rather, see that it’s responsibly used. It’s also important that children aren’t just in their rooms and spending hours and hours on the computer but that they actually openly talk about it. I think that whether it’s bullying or cyberbullying, the most important thing is that you have lines of communication; and the lines of communication are best if you’re neither harsh—like “Fight back!”—nor overprotective, in that you immediately run to the school and involve everyone, so that the child feels humiliated a second time because the parents made such a fuss. The important thing is that kids are open and can talk to you: “This is happening to me. What can I do?” Parents need to be sympathetic but not overreact. And children themselves very often have good suggestions; for example, “Could I defriend this person, or have another e-mail address and give it only to safe friends, and ignore the other address?”

GS Because they not only know the bullies at school, but they also know who among their peers may be able to offer support.

DW Yes, but the parents can also do something to help them develop friendships. You’re less likely to be victimized if you have friends who defend you. For example, when you get into a new classroom, it’s important to see whether there could be sleepovers, to organize games or activities—so that you meet the peers that can protect your child and who can help your child make friends, because it can be hard.

GS It makes a difference when parents can be involved in school as well. It not only shows your children they have someone on their side but also shows their peers you’re involved, which perhaps makes your children less of a target.

DW It also gives you opportunities for communication with your child’s peers. If you go on trips, you talk to other children as well and they can talk to you—and maybe they’ll actually think, “He actually has kind of a cool mom.”

GS As far as prevention is concerned, some of the research suggests having a schoolwide intolerance of bullying. Is that what you’ve found?

DW The most frequently evaluated method is one developed by a Swede working in Norway, Dan Olweus, which involves a whole-school policy. Teachers are aware of the policy, and children are aware of what is acceptable, and the administration and parents all work together. They are shown videos so they can learn how to deal with a bullying situation. There are clear rules about how this works.

Another issue is that primary-care doctors and nurses should be much more aware, so when they see symptoms, they think about the potential of bullying. Someone may talk to a doctor but may not talk to teachers, because they feel they’re not going to help.

We have to see that bullying is really a community problem; it occurs within the society. You mentioned sibling bullying before; that’s another area we work on—surprisingly ignored. Over 90 percent of all children have siblings, and that’s how they learn how to behave toward peers. We found that those who were victims of bullying by siblings at home were three times more likely also to become victims at school.

So, there’s something parents can do—and it starts in the home.