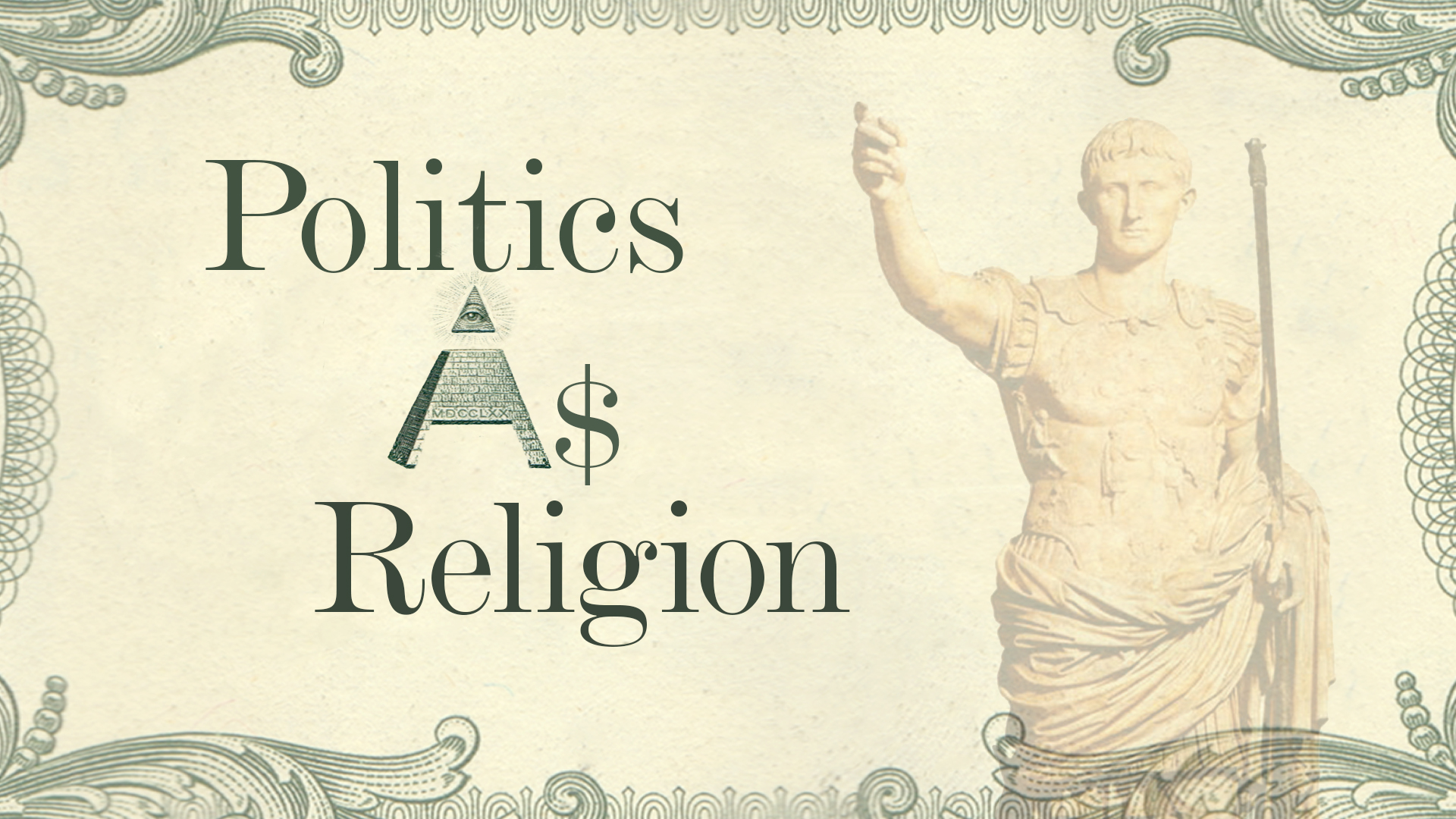

Politics As Religion

It’s often been said that religion and politics don’t mix. Perhaps that’s why the rules of etiquette used to require avoiding either in social conversation. From the Roman Empire to modern democratic systems, history demonstrates that politics and religion have long been intertwined.

The role of religion in political life has come to the fore again in recent years. It used to be said that religion was dead and that its role in public life was over. The idea was that as societies became more and more secularized and modernized, religion was bound to retreat. But religious elements were present in all the world’s political systems, from totalitarian to democratic. Of course, there’s been much more focus on religion in public life with the recent rise of fundamentalisms of various kinds, both Christian and Muslim, and with the collapse of the Soviet system.

Italian author and historian Emilio Gentile has focused on what he calls the “sacralization” of politics—that’s to say, making aspects of a secular political system into something bordering on the holy or sacred. This predates by many years the recent emergence of religion as a force of international affairs.

In a Vision interview he explained in more detail what he means by sacralization: “Well, sacralization of politics means that some secular entity in politics—like ‘the Fatherland,’ ‘the Race,’ ‘the Revolution,’ ‘the Proletariat’—becomes absolute and commands obedience. People want to believe that these secular entities are, in a sense, the giver of the meaning of life, and you have to sacrifice your life; in any nation you sacrifice your life for war to save the country. And in this way the country becomes a secular god, a secular godliness. Whenever you sacralize these political entities, which are secular entities, you transform them into a kind of absolute entity, giving meaning to life and giving the ultimate goal to life. You are sacralizing politics, which is very different from any use of religion in terms of politics, or using politics in terms of traditional religion.”

Gentile’s studies range across all political systems. When asked to detail some of the elements of political sacralization in today’s world, he began, perhaps surprisingly, with one of freedom’s symbols: “I think there is a very common object that you can see right now: the [American] dollar bill. When you turn a dollar bill, you have the national motto, “In God We Trust.” But there is no definition of God in this sentence. Is it the biblical God? Is it the Muslim God? No, it is “In God we trust”—the God of America. You have the symbolism of the great seal, the pyramid, the holy eye, and then the two Latin sentences. All are religious symbols, but they are related not to the God of the Bible, or the Christian God, or the Muslim God. They are related to the American entity, to the American nation, to the American republic.

“And then you can also see all the symbolism in the United States monuments; for instance, the Lincoln Memorial. I think it’s very difficult to approach the Lincoln Memorial without having a sense of religiosity, of sacredness surrounding Lincoln in that temple. This is a clear example of the sacralization of politics, because Lincoln was not a God-sent son, he was a political figure.”

Professor Gentile’s comments may be rather shocking to some. This is not to suggest that we shouldn’t cooperate with government, but rather that we recognize that most governments use religious elements.

Jesus was approached on a related matter by His opponents. In an attempt to trap Him, they asked, “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not?” He asked whose image was on the coinage. Of course, it was Caesar’s. His reply, then,was “Render . . . to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:15–21). In so doing, He avoided their trick question and at the same time drew a distinction between the secular and the religious, while indicating that both require compliance.

What remained unspoken was what happens when there is a conflict between man’s laws and God’s laws. For the believer, the apostle Peter supplies the answer, “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). Countless people over the centuries have had to make that decision and take the consequences.