Benjamin Spock: Physician, Heal Thyself

“The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world” is a familiar and powerful adage. After all, perhaps no person exerts more power on a young person’s life than his or her mother. Yet in postwar Western society, no person has had more influence on mothers than Benjamin McLane Spock, author of the best-selling self-help manual Baby and Child Care. Since his book first appeared in 1946, it has sold more than 50 million copies in seven editions and has been translated into 39 languages, making it, by some accounts, second only to the Bible in popularity.

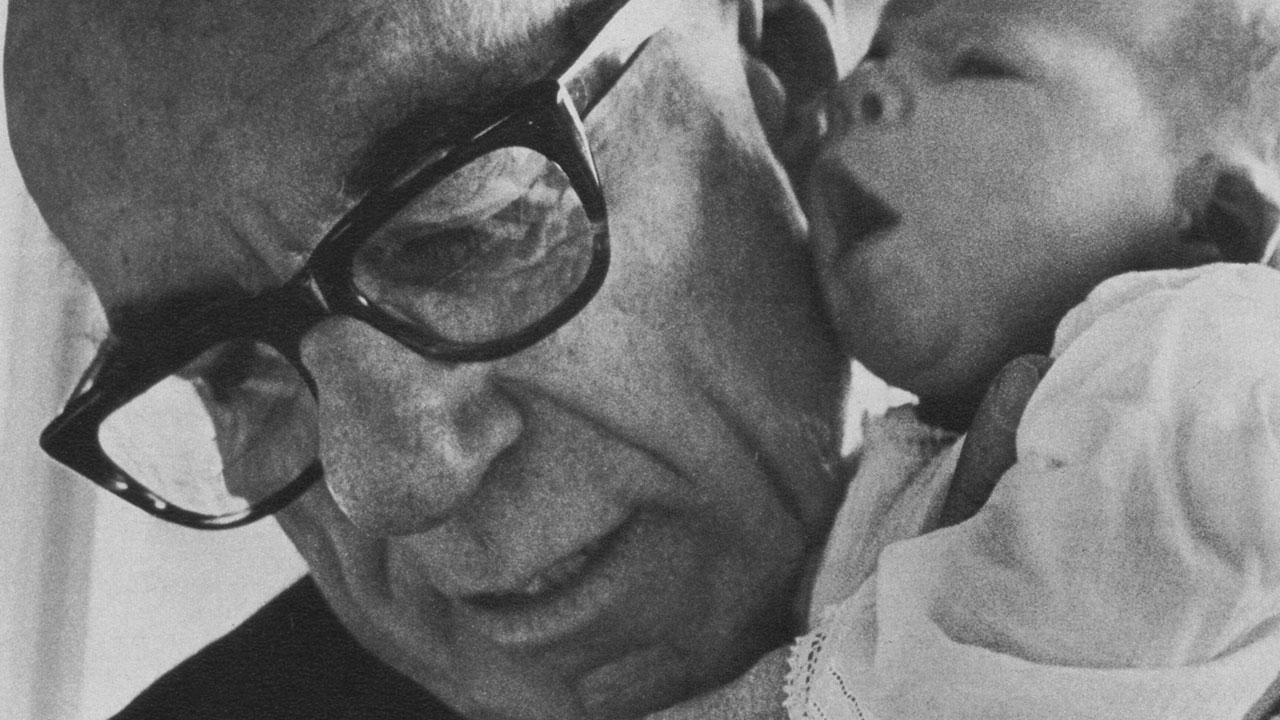

Generations of children around the world have been reared on Spock’s fatherly advice, dispensed in a simple, straightforward and reassuring style. Indeed, Spock’s book became the modern bible of baby care, and he himself enjoyed near universal acclaim as America’s favorite doctor.

The oldest of six children, Spock was born to a prosperous family in New Haven, Connecticut, on May 2, 1903. His father was a Yale-trained lawyer who became general counsel to the local railroad company. His mother also came from a distinguished background.

Spock enrolled in Yale University in 1921, where he met and fell in love with Jane Cheney. Though his academic accomplishments were relatively modest, he was a strapping 6-foot-4-inch bastion of the rowing crew, which won a gold medal for the United States in the 1924 Paris Olympics.

Having decided on a career as a children’s doctor, Spock went on to the Yale Medical School in 1925. In 1927 he and Jane were married, and Spock transferred to Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. He graduated at the top of his class in 1929, and a two-year internship followed.

Spock’s experience with children made him realize that half the questions parents asked related to psychological issues. He became convinced that pediatricians should have training in psychology, and that Sigmund Freud’s insights provided a better framework within which to encourage child development than the harsh, rigid and moralistic approach of his own parents.

By 1937 Spock became a board-certified pediatrician and was increasingly captivated with the goal of changing America’s child-rearing practices. By the early ’40s he was ready to commit his ideas to a book that would emphasize positive, commonsense, practical advice. It would embody the most up-to-date answers to all the problems that mothers might encounter during their children's development from infancy through puberty. It would seek to correct the deficiencies of his own upbringing (as revealed through psychoanalysis). He hoped it would revolutionize the way children were raised.

When the book appeared in 1946, Spock’s positive, can-do, deliberately nonauthoritative tone took America’s mothers by storm. Spock insisted mothers could trust their own judgment. He succeeded in establishing a more sympathetic, child-centered approach, and in the process he became a national phenomenon.

Spock began a nationwide TV show in 1955 and went on to write a monthly magazine column. In the early ’60s, as he approached the age of 60, he became politically active, joining in the protest over the development and testing of nuclear weapons. He also became increasingly active in antiwar demonstrations, lending high-profile support to draft dodgers and various antiestablishment causes associated with the youth of that decade. Spock consistently urged greater political action by parents to force governments to adopt more socialistic policies that, he believed, would better care for people's needs.

He developed considerable visibility in politics; in 1972 he actually ran for U.S. president as a left-wing third-party candidate. But his political activism won him numerous detractors, who succeeded in branding him “the father of permissiveness.” And indeed, his child-centered approach was often misapplied or taken to extremes. He began to feel the heat of public criticism. It seemed Spock’s theory of “ideal families according to Freud” was turning into another great American dream-cum-nightmare. The “Spock babies” were adults now with their own children, and the so-called Spockmarks were beginning to show.

Spock himself swung back and forth on the pendulum of dissent with each new reprint of his book, trying to counter criticisms of permissiveness, selfish materialism and antifeminism. In response to accusations that he taught a laissez-faire approach to child rearing, he stressed in later editions that children need standards, and that parents, too, have a right to respect. He constantly sought to keep his material updated to be in line with the changing times—one of the reasons for his book’s enduring success.

Yet for all his compassionate advice to the mothers of the world, Spock mirrored his father’s inability to give his own sons the love they needed. Grandson Peter’s suicide and Spock’s divorce after 48 years of marriage (because of his wife’s repeated breakdowns, induced by alcoholism and medication abuse) shattered the image of the ideal family man.

The life of Benjamin Spock is an amazing story of publicly displayed success that had a private world of familial dysfunction.

The life of Benjamin Spock is an amazing story of publicly displayed success that hid a private world of familial dysfunction. It is also the story of how Freud’s humanistic philosophies were surreptitiously introduced into the mainstream of American family life—with clearly questionable consequences.

In the final years of his life, Spock was telling his readers to follow his writings and not his example, knowing that as a father he had fallen far short of the ideals his book embraced. Yet while he recognized the serious shortcomings of the rigid child-rearing methods of the past, and while he may have provided parents with some solid, commonsense advice, the weight of evidence suggests that ultimately Spock’s ideas have not helped to produce more secure and well-adjusted children and adults. He saw the need for morals and values, but he failed to recognize that they stem from a godly perspective. What he never understood is that the positive changes he sought are simply unachievable on the basis of humanism.

Spock died in 1998 shortly before the seventh edition of his book went to press.