Warning! Warming World

Our overheating planet is already showing evidence of climate breakdown. What can we still do about it?

A geologist who’s been visiting the same cliff face in Greenland every summer for about 20 years has noticed a big change in the landscape. Where he once crossed icy ground to reach his research site, he now crosses a sandy beach. For him climate change is an established, observable fact.

According to the journal Nature, Greenland recorded its highest temperature in 1,000 years in 2023. The article concludes that human activity has contributed to a warming trend that began in 1800 and could have far-reaching effects: “The disproportionate warming is accompanied by enhanced Greenland meltwater run-off, implying that anthropogenic influence has also arrived in central and north Greenland, which might further accelerate the overall Greenland mass loss.”

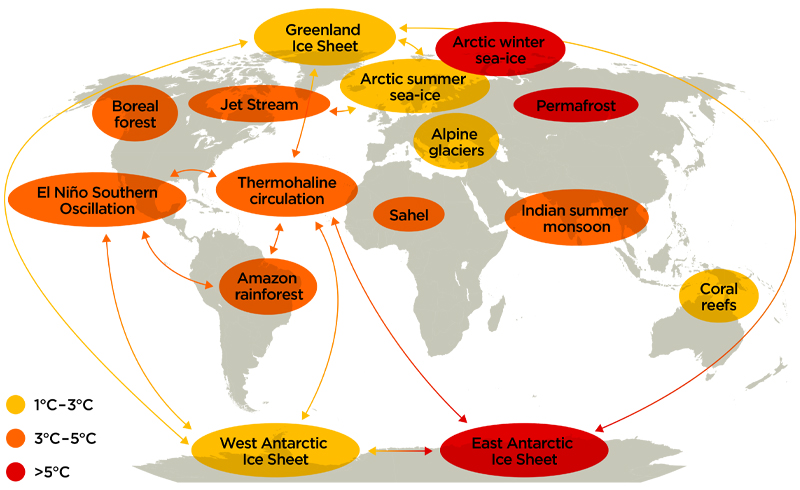

What is happening to the Greenland ice sheet may be a tipping point that triggers other major climate-related changes, including altering the Atlantic circulation pattern (see Figure 3 below). At the same time, the preliminary 2023 global temperature was also the hottest on record: 1.4°C above preindustrial levels, benchmarked at 1850–1900. In 174 years of recordkeeping, the last nine have been the warmest, adding to concerns about rising sea levels and record-breaking concentrations of greenhouse gas, including methane.

“The evidence from tipping points alone suggests we are in a state of planetary emergency, where both the risk and urgency of the situation are acute.”

There is, of course, debate about the cause of this dramatic global shift. As climate change has become a political football, the debate has become so acrimonious that meteorologists in several countries—including the United Kingdom, Spain, France, Australia and the United States—have suffered harassment and even death threats for their on-air comments on climate change.

On one side, some dismiss the human impact, believing that we can have little effect on such a massive Earth system. They say that no amount of increase in greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, chlorofluorocarbons, nitrous oxide) can cause such a change.

Others, however, counter with historical details of scientific inquiry into the underlying dynamics. For example, the warming trend that played out in front of the geologist in Greenland was accurately predicted back in 1972. In an article published that year in Nature, meteorologist John S. Sawyer predicted an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and a corresponding rise in global temperature of 0.6°C by 2000. The actual temperature increase was 0.5°C. Although Sawyer acknowledged that much more research was needed, more than 50 years ago he was able to conclude, “In spite of the enormous mass of the atmosphere and the very large energies involved in the weather systems which produce our climate, it is being realized that human activities are approaching a scale at which they cannot be completely ignored as possible contributors to climate and climate change.”

But the idea of a link between global warming and heat trapped in the atmosphere was not new even then. It had been proposed in the previous century by French scientist Joseph Fourier. In 1824 he noticed that the earth was warmer than its distance from the sun suggests, and he concluded that the atmosphere was storing heat. At the end of that century, Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius observed that CO2 in the atmosphere was effective at trapping heat and predicted that the huge increase in burning coal for industrial purposes would increase atmospheric CO2 and warm the planet.

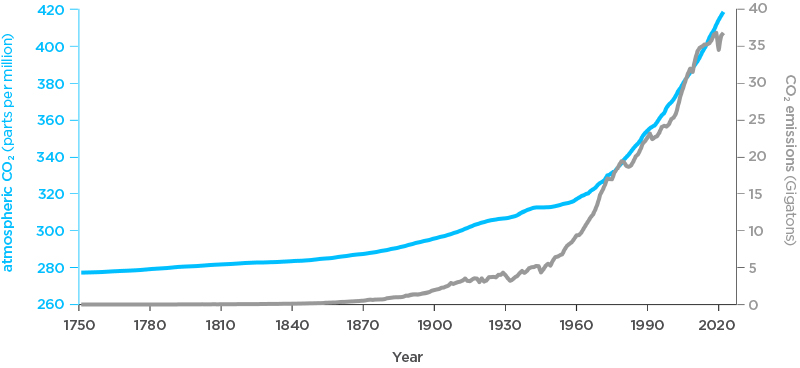

Two significant findings in the 20th century further established the link between CO2 and global warming; in 1938 British engineer Guy Callendar showed that the half degree rise in temperature over the previous 50 years was consistent with increases in CO2 from industrial production and coal burning; and in 1958 US scientist Charles Keeling linked the rising amount of CO2 in the atmosphere to the growth of the human population. In 1750 it was less than 280 parts per million (ppm), rising exponentially along with world population and industrialization to about 420 ppm by 2020.

Figure 1: CO2 Emissions vs Concentrations 1751–2022. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (blue line) has increased along with human emissions (gray line) since the start of the Industrial Revolution in 1750. Emissions rose slowly to about 5 gigatons—one gigaton is a billion metric tons—per year in the mid-20th century before skyrocketing to more than 35 billion tons per year by the end of the century.

Source: NOAA Climate.gov graph, adapted from original by Dr. Howard Diamond (NOAA ARL). Atmospheric CO2 data from NOAA and ETHZ. CO2 emissions data from Our World in Data and the Global Carbon Project (May 12, 2023). Used with permission.

From this two-hundred-year history of the role of heat in the atmosphere, we can certainly see that human activity is implicated in climate change. And unlike today, this history shows no politicization of the issue, nor any suggestion by others of deception or hoax on the part of the scientists involved.

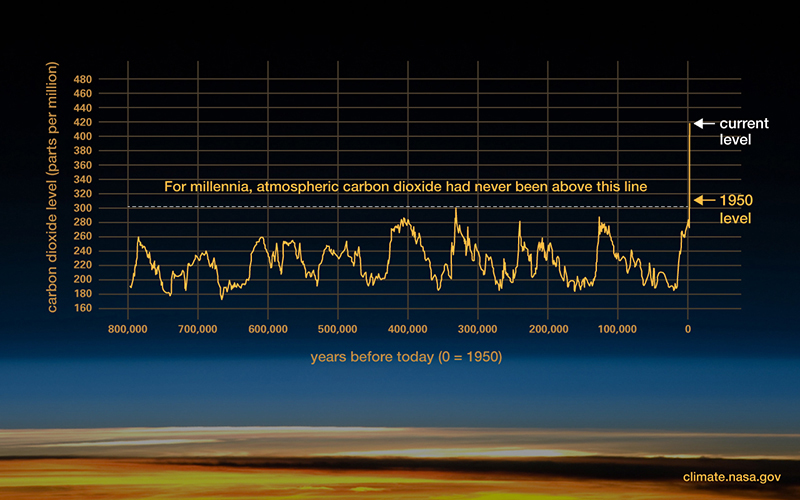

Figure 2: The Relentless Rise of Carbon Dioxide. Ancient air bubbles trapped in ice enable us to step back in time and see what Earth’s atmosphere and climate were like in the distant past. They tell us that levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere are higher than they have been at any time in the past 400,000 years. This graph not only conveys the scientific measurements; it also underscores the fact that humans have a great capacity to change the climate and the planet.

Source: NASA Global Climate Change

In 2023, the UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) discussed ways to control the problems caused by global warming; 196 nations had signed the 2015 COP21 Paris Agreement and had set a goal of limiting global temperature increase to no more than 1.5°C by the end of this century. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assesses the science behind climate change. For the 2018 follow-up “Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C,” they gathered input for policymakers from 86 experts in 39 countries. They confirmed with “high confidence” that “global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if it continues to increase at the current rate.”

“Even if the Paris Accord target of a 1.5°C to 2°C rise in temperature is met, we cannot exclude the risk that a cascade of feedbacks could push the Earth System irreversibly onto a ‘Hothouse Earth’ pathway.”

Unfortunately, nations have so far failed to live up to their 2015 commitments, creating what the late climatologist Will Steffen and others have called a “planetary emergency.” The fact that little has been achieved despite previous commitments to agreed targets perhaps speaks to the lack of willingness to change on the part of some fossil fuel producers and top users. They form a powerful lobby and show little inclination to promote an end to fossil fuel dependency, preferring to talk in terms of “phasing down” rather than “phasing out.” Russia, Saudi Arabia and China do not support an immediate end to fossil fuel use. And while COP28 ended with a communiqué that spoke of ending fossil fuel dependency, it remains to be seen whether that goal can be achieved in time.

Right now, the problem isn’t just that the world is getting hotter and hotter, it’s that we may have set off a “global tipping cascade,” in the words of Steffen and his colleagues. In 2019 they noted that 9 of the 15 known global climate tipping points that regulate the state of the planet have been activated.

Another example of a tipping point causing the sudden release of CO2 and methane into the atmosphere would be the irreversible thawing of Arctic permafrost.

Figure 3: Global Map of Potential Tipping Cascades. The individual tipping elements are color coded according to estimated thresholds in global average surface temperature (tipping points). Arrows show the potential interactions among the tipping elements that could generate cascades. Note that, although the risk for tipping (loss of) the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is proposed at >5°C, some marine-based sectors in East Antarctica may be vulnerable at lower temperatures.

Source: Will Steffen et al., “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene,” PNAS (August 2018). Used with permission.

Accordingly, Steffen said, “we are already deep into the trajectory towards collapse” of civilization. That is, whether or not we succeed in reducing emissions, it may already be too late to prevent a “Hothouse Earth.”

With this level of threat on the global doorstep, King Charles III made an impassioned plea to the world leaders and delegates at COP28: “We are taking the natural world outside balanced norms and limits, and into dangerous, uncharted territory. . . . Our choice now is a starker and darker one: How dangerous are we actually prepared to make our world?” There is a not-so-subtle moral and ethical imperative in this appeal. And that is where the focus must now be for leaders and citizens alike.

Ahead of COP28, UN secretary-general António Guterres sent a video message to the more than 200 participants of the Global Faith Leaders Summit who had gathered in Dubai to discuss climate change. He said, “We need the moral voice and spiritual authority of faith leaders globally to summon the conscience of world leaders, awaken their ambition, and inspire them to do what is needed.”

“As we stand at the precipice of history, considering the gravity of the challenges we collectively face, we remain mindful of the legacy we will leave for generations to come.”

Human nature left to its own devices is unlikely to come to the negotiating table with moral/ethical priorities at the forefront. Self-interest usually wins out. But in the face of a planetary emergency, is there any other option? Could radical change still bring a reprieve? There is some good news. Despite all that lies ahead, there is hope.

Climate scientist Kate Marvel, a lead author of the US Fifth National Climate Assessment (2023), recently gave some reason for optimism. Although her team was right about the consequences of negative climate change trends, she sees signs of improvement: “Extreme events like heat waves, floods and droughts are becoming more severe and frequent, exactly as we predicted they would. We were proved right.” But she adds, “In the last decade, the cost of wind energy has declined by 70 percent and solar has declined 90 percent. Renewables now make up 80 percent of new electricity generation capacity. Our country’s greenhouse gas emissions are falling, even as our G.D.P. and population grow.”

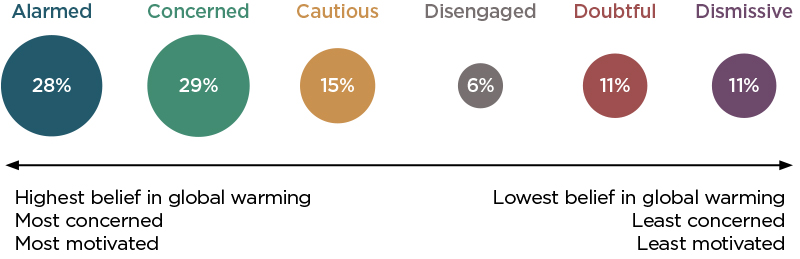

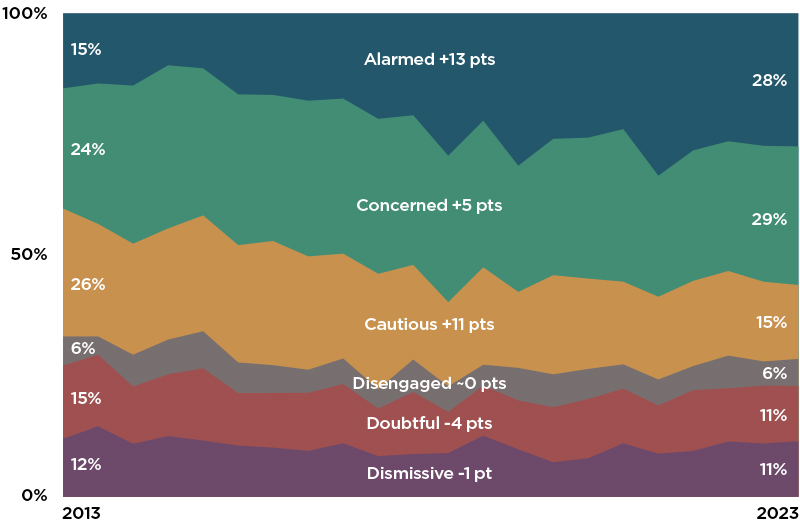

The glimmer of hope she sees is that the United States has responded to climate change warnings at state, local and tribal levels. But she acknowledges that more people need to get on board. She is not as concerned about reaching the fossil fuel industry or climate deniers as she is about reaching other groups, as described in the Yale and George Mason Universities’ program on Climate Change Communication. They identify the six audiences within American society regarding climate change as the Alarmed, Concerned, Cautious, Disengaged, Doubtful and Dismissive.

Figure 4: Global Warming’s Six Americas, Fall 2023.

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication; George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. Used with permission.

The shifts within these audiences over the decade 2013–2023 are instructive. By fall 2023, 57 percent of the population were alarmed or concerned about climate change—up from 39 percent in 2013—while the disengaged, doubtful and dismissive sat at 28 percent, down from 33 percent in 2013.

Figure 5: Global Warming’s Six Americas Over the Last Decade.

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication; George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. Used with permission.

Understanding and acting on what the future holds for our children and grandchildren and future generations if the 1.5°C target is exceeded is the moral and ethical imperative we must meet. A quote often attributed to German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer declares, “The ultimate test of a moral society is the kind of world that it leaves to its children.” This would certainly apply to every citizen in the world in general, and at this moment has particular application to the global environment. Good stewardship of the earth is emphasized at the beginning of the biblical record. The idea of dressing and keeping the Garden of Eden required Adam to cultivate and pay careful attention to it. There's an underlying sense of moral responsibility for the earth here in serving and preserving it. And as several authors have shown, there are practical steps we can all take to make a positive impact today.

For example, Julian Cribb’s How to Fix a Broken Planet: Advice for Surviving the 21st Century details several personal strategies for cooling the earth. The most immediate contribution we can make, he says, “is to lower our personal consumption of everything, especially consumer goods; textiles and clothing; items of machinery and equipment; building materials; travel and transport; goods imported from far away; and luxury foods—and recycle more and waste less. It is our overconsumption of goods that is the chief driver of climate change—and we have to get it under control or else rob our grandchildren of their future on a habitable planet.”

This is our urgent moral duty. Leaders and industrialists have their part to play. Instead of engaging in short-term thinking and political and economic compromise, they must act now for the greater long-term good. Citizens can do more at the individual level as outlined above.

What is certain is that without immediate action we will condemn our descendants and all life post-2100 to a catastrophic fate at 3°C above preindustrial levels. They deserve better, and we can all do better.