Forever Chemicals, Forever Troubles

The Unforeseen Consequences of PFAS Convenience

Sometimes what seems like a great idea can go wrong—very wrong.

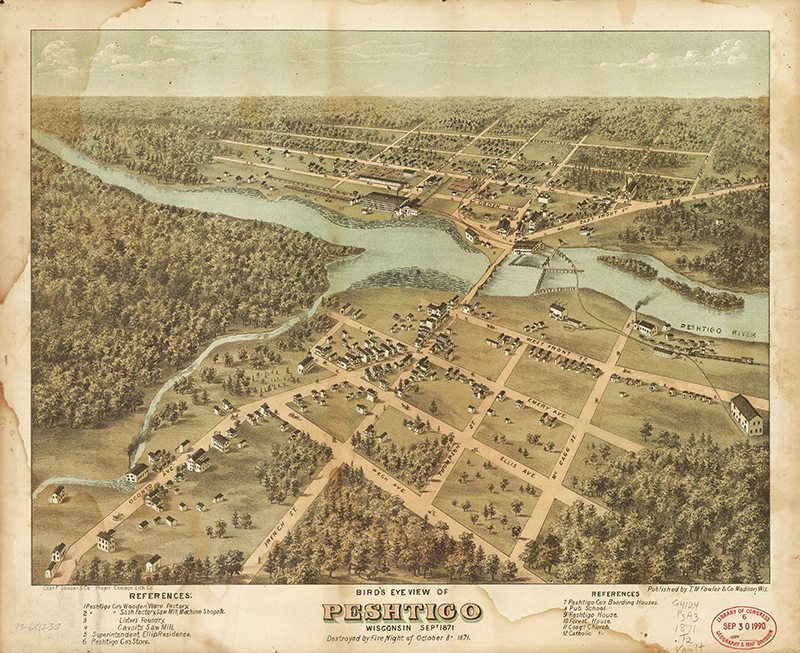

Built on a river and surrounded by peat bogs and pristine forests, the future of 19th-century Peshtigo, Wisconsin, appeared secure. The town was prosperous and growing rapidly, thanks to the seemingly unlimited natural resources nearby. Peshtigo was home to the world’s largest wood products facility; with the help of the newly formed timber industry, they felled old-growth trees and barged the wood to Chicago, about 250 miles (400 km) to the south, to feed the demand for building materials there.

But the fall and winter of 1870 had been unusually warm, with little rain. Spring brought no relief, and drought conditions worsened over the summer. The bogs dried, the trees lost their leaves early, and the pines dropped their needles, turning the territory into a tinderbox. Some blame meteor showers, sparks from railway cars, or stump burning from land clearing, while others say we will never know why it is that several small fires, fanned by 100-mile-per-hour gales, grew into a merciless firestorm that destroyed a million acres. Peshtigo was completely destroyed; 16 other communities were also burned, most faring only slightly better than Peshtigo. Between 1,500 and 2,500 lives were lost that October, including entire families, but because official records were gone too, the final numbers will never be known. Officials estimated the damage at around US$169 million, about the same as the Great Chicago Fire of 1871—which, coincidentally, began on the same night. The Peshtigo Fire remains the worst wildfire disaster in US history.

In time, the forest regrew and so did the towns. As the 20th century progressed, researchers began developing fire-retardant synthetic chemical compounds, and what better place to test them than the Peshtigo area, where locals had a keen personal interest in their potential life-saving benefits. A 380-acre Fire Technology Center (FTC) in Marinette, Wisconsin, opened in the 1960s and continued operations unfettered for the next half century.

But Peshtigo was in for another disaster. Late in 2013, the FTC’s parent company discovered chemicals known as PFAS in the FTC’s groundwater. (PFAS, variously pronounced P-fass, P-fahz or pee-ef-ayz, is a plural noun that stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.) As groundwater isn’t contained within property lines, we might reasonably expect that the company immediately informed nearby residents that their own well water could also be contaminated and unsafe to drink. Yet it was four years before they issued that warning to their neighbors. One family found that the surface water in the creek next to their house—where their children played—measured 300 times the current federal health advisory level for PFAS of 4 ppt (parts per trillion). Wildlife was also affected, and hunters were warned to avoid eating organ meat from local venison. For some in this largely rural area of Wisconsin, it was the first they’d ever heard of PFAS.

Prevalent and Persistent

PFAS are essential ingredients in fluoropolymer coatings and products. They undeniably bring convenience to our busy lives, in that they resist water, oil, grease, stains and heat. Fluoropolymer coatings are therefore common on such everyday items as clothing, furniture, food packaging, nonstick cookware and electrical insulation. The chemicals are also a component of lubricants and some adhesives. Why, then, are they a problem?

It’s now known that they take hundreds or perhaps thousands of years to break down, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals.” And of the thousands of variations of these synthetic compounds, only a relative few have been tested for safety. Further, many are combined with other synthetic chemicals, and testing the effects of PFAS in these innumerable combinations is an impossible task. As a result, we simply don’t know what the “cocktail effect” may be.

We do know that many PFAS (also known as PFCs) are known carcinogens and endocrine disruptors, which can generate a range of detrimental health effects throughout our lives—and the lives of future generations.

How humans react to PFAS depends on the individual; life stage, gender, genetics, and the cocktail effect of other chemical exposures all come into play. They build up in the body over time, and bioaccumulation begins early. The unborn children of exposed mothers are particularly at risk, because a tiny dose at the wrong time can affect their development in significant ways. The risks aren’t completely understood, but PFAS (and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals) have a troubling array of them.

Beyond the womb, these toxins threaten our health from infancy through adulthood. They’re thought to disrupt blood-brain and intestinal barriers, gut microbiota, the transcription of selected genes, and the synthesis, secretion and distribution of sex hormones. Neurological and behavioral disorders may result from exposure to PFAS. Babies can take in the chemicals through ingestion, inhalation of dust, and absorption through the skin when they wear fire-retardant clothing or sleep on treated textiles, crawl on waxed or vinyl flooring and synthetic carpets, play on artificial turf, and put things into their mouths—just doing what babies typically do. In the words of Philippe Grandjean, professor of clinical pharmacology, pharmacy and environmental medicine at the University of Southern Denmark and founding editor of the journal Environmental Health, “I think it’s a disgrace. It is unethical what we have done.”

“Clearly there are many chemicals that can affect fertility, so this is also a problem for the human race. We are apparently affecting our chances of having heirs, of having children and grandchildren. And . . . we are poisoning them from the beginning.”

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and others warn that exposure can lead to a number of developmental effects in children, including low birth weight, early puberty and impaired skeletal development. In people of all ages, it can lead to behavioral changes and general damage to the nervous system. Immunotoxicity can show up in the form of reduced ability of the body’s immune system to fight infections, including impaired antibody response to vaccines and increased risk of fevers and hospitalizations for such infections as pneumonia and COVID-19. Other effects include interference with the body’s hormones and metabolism, increased cholesterol levels and risk of obesity, changes in liver enzymes, and increased risk of cancers. These chemicals can cause fertility issues in both men and women, and women who do become pregnant may have an increased risk for hypertension and preeclampsia. The effects of PFAS are clearly wide-ranging and persistent in the body. “The more we look, the worse they appear,” warns Grandjean.

Award-winning Australian science writer Julian Cribb, author of several books outlining the existential threats facing humankind, told the audience at a 2022 international conference in Adelaide, Australia, that industrial chemicals had doubled in output since 2000. It was up to around 2.5 billion tons a year, and that rate is forecast to triple by 2050.

Cribb has long described a global chemical “tsunami” that includes forever chemicals like PFAS. He reported to the Adelaide conference that “they travel on the wind, in water, attached to soil particles, in dust, in plastic fragments, in wildlife, in food, drink and trade goods, in and on people.

“They combine and recombine with one another, and with naturally occurring substances, giving rise to generations of new compounds, some more toxic, others less so. . . .

“They leapfrog around the planet in cycles of absorption and re-release known as the grasshopper effect.”

Profitable Poisons

It’s easy to say that we must avoid PFAS chemicals. But they’re everywhere, and they do seem, at first glance, to make our lives easier and better. We find them in cleaning products (as surfactants), water-resistant fabrics (such as rain jackets, umbrellas and tents), wrinkle-resistant clothing, and children’s fire-retardant pajamas. Our food is wrapped in PFAS-aided grease-resistant paper and may have been cooked in PFAS-infused nonstick cookware, and much of our popcorn comes in convenient microwavable bags that also contain PFAS. The chemicals feature in personal care products (shampoo, sunscreen, dental floss, nail polish, waterproof makeup) and find their way into personal hygiene products (diapers, feminine paper products, menstrual cups). Stain-resistant PFAS coatings are used on carpets and upholstery. They’re found in fertilizers and guitar strings, pesticides and paint. In the farthest reaches of our planet, PFAS are in our wastewater and our drinking water, in our steaks and seafood—in fact, throughout our food system. They’re also in the blood of Asian pandas, Arctic polar bears and Antarctic penguins.

Even our rainwater can contain high concentrations; and as discarded PFAS-infused products decompose in our landfills, the chemicals leach into our groundwater. Some escape into the air in dust particles, thus traveling in the air we breathe. Further, they hide in the micro- and nanoplastic particles that infest our world, our bodies and our brains.

Manufacturers of these synthetic chemicals (3M, DuPont and others) knew that they posed significant health threats shortly after their introduction in the mid-20th century. In the 1960s, researchers found organofluoride compounds in human blood—the first evidence that an industrial compound could transfer to a human in such a way. More studies found more contamination and even proof that these chemicals can pass to the next generation via prenatal and early postnatal exposure—the most sensitive periods of organ, brain and systems development. Corporations kept that information close to the chest until lawsuits forced the release of internal documents nearly 40 years later. Even the EPA has known of the dangers of PFAS for decades; but legislation is slow, thanks in part to lobbyists employed by manufacturers to help protect their financial interests.

“Research on the health effects of PFAS began in the 1950s. Studies at that time demonstrated that certain PFAS compounds could bind with proteins in human blood and could accumulate within the bloodstream and liver.”

As early as 1935, DuPont promised “Better Things for Better Living . . . Through Chemistry.” And on a certain level, they and similar companies delivered. Brands such as Scotchgard, Stainmaster, Astroturf and Teflon—part of our collective vocabulary and part of our homes and public spaces for much of our recent history—certainly did bring stain-free, nonstick, no-iron, no-mow and no-burn convenience. But these “better things” have been shedding PFAS for decades. Corporations made untold profits while knowingly allowing humanity and the environment to suffer in ways we won’t completely understand for a very long time. When we consider the significant delays in the discovery of PFAS toxicity, the dissemination of important findings and knowledge, and governmental regulatory decisions—not to mention the delay in taking toxic materials off the market—we see the embodiment of the human proclivity for selfishness and greed over care and concern for others.

PFAS, their replacements, and other synthetic chemicals could be considered necessary; for example, in lifesaving medical applications or preventing another disaster like the Peshtigo Fire. Yet even the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) calls the PFAS used in firefighter turnout gear “an unnecessary—and serious—occupational threat.” It’s ironic that a substance added with the goal of increasing safety is correlated with increased disease and deaths. IAFF general president Edward Kelly, referring to the PFAS-infused suits, warned, “Cancer is the number one killer of fire fighters, and for years, corporate interests have put profits over our lives.” Such effects may have been unintentional at the outset, but continuing to market PFAS as safe after the facts were known has caused untold harm to human lives and the environment. And as already noted, the consequences will continue far into the future.

Slowing the Tsunami

Fortunately, awareness of the PFAS problem is increasing globally, prompting the search for solutions.

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) is a United Nations treaty signed in 2001. Its aim is to reduce or eliminate the production and use of key polluting organic compounds that are difficult to break down. (The term organic compound refers to a chemical compound created by bonding carbon with another element.) The Stockholm Convention has since been amended to restrict or eliminate PFAS chemicals including PFOS and PFOA, while discontinuing some previously allowed uses.

Most major countries around the world have recommended limiting their use, but since PFAS are manufactured globally and not all countries limit them, their unregulated international production could potentially offset the global reduction anticipated with US and European phaseouts.

Even so, there are other encouraging developments. When the dangers were publicly exposed, some companies—including Scotchgard, Teflon and others—began to step away from PFAS, phasing in new formulae (some of which, it should be noted, are still problematic). The EPA finally proposed adding several types of PFAS to the US Federal Register of Hazardous Constituents in 2023, and they decreased the maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) in drinking water from 70 ppt to an intermediate goal of 4 ppt for PFOA and PFOS. Research is ongoing, so US and European standards may change as we learn more. Several states and some countries have banned PFAS in food packaging or restricted the use of PFAS-based firefighting foam. The European Chemicals Agency is proposing further limits on the use of PFAS (with a few exceptions, such as in medical applications).

“Various sources of PFAS contamination have triggered more than 6,400 lawsuits since 2005, including at least 1,235 filed in 2021 alone.”

In the United States, California is phasing out the use of PFAS, requiring municipal tap-water testing and transparency and giving individual cities the power to ban artificial turf and the use of PFAS chemicals in textile and garment manufacturing. In February 2024, the Federal Department of Agriculture (FDA) announced that PFAS-treated greaseproof paper and paperboard (if their use relates to food) is no longer being sold in the United States. The announcement explained that “this means the major source of dietary exposure to PFAS from food packaging like fast-food wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, take-out paperboard containers and pet food bags is being eliminated.” In March 2024, the EPA released its National Analysis, showing that environmental releases of toxic chemicals from facilities covered by the program were 21 percent lower in 2022 compared to 2013. And promising new research suggests that certain bacteria and fungi can be used to help break down some PFAS.

In the meantime, the city of Peshtigo filed a lawsuit against Tyco Fire Products and other companies, seeking repayment for expenses related to dealing with local PFAS contamination. In September 2022, Tyco unveiled a groundwater treatment and extraction system that they hope will remove 95 percent of PFAS from the contaminated groundwater.

These are all steps in the right direction. But in a 2018 interview, Cribb told Vision that we “cannot fix these problems one at a time. If you try to adopt simple solutions to one particular threat, you often make matters worse elsewhere.”

And that is the essence of what is happening with these persistent pollutants. Many of the harmful “long chain” PFAS (with seven or more carbon atoms) are being phased out, and related “short chain” PFAS (six or fewer carbon atoms) are being introduced as substitutes, with manufacturers claiming that the structural change makes them safer. Some of these seem to have properties similar to the original PFAS, though some do break down—albeit very slowly—in the environment. Still, there are few scientific studies on the new generation of PFAS chemicals, and research thus far shows dangers similar to those of their predecessors. In certain cases, it appears that the short-chain replacements have even higher endocrine-disrupting potential than the long-chain originals. We simply don’t know enough about them yet. PFAS substitutes and other persistent industrial chemicals need to undergo intense scrutiny and careful consideration before they’re put to widespread use.

The reality, of course, is that as long as there’s both demand and a profit to be made, manufacturers will continue to produce these chemicals. So it’s up to each of us to take personal responsibility to help our future progeny and our planet.

“I hope that what I’ve told you now is not completely depressing,” said Grandjean after describing the problems with PFAS, “but you can also see that maybe there’s a way out through this.” With our collective individual efforts, we can “think as a species,” to quote Julian Cribb; together we can make a difference. Many will recall that in the mid-2000s, consumers stopped buying baby bottles, water bottles and other products that contained possibly carcinogenic and endocrine-disrupting bisphenol A (BPA). Even though the US FDA and the European Food Safety Authority declared BPA to be safe as commonly used, retailers listened to the consumers and began pulling items made with BPA from the shelves. The next year, legislation to ban BPA in children’s food containers in the United States commenced. “And that way we got better and safer products because of consumers,” said Grandjean.

In that same 2018 Vision interview, Cribb explained the power of the consumer: “We can actually have more influence on the world as consumers than as voters, because . . . our economic messages will actually discipline industry, and they will influence government. So just in the way you live, you can influence the whole of the economy.”

Doing this means deciding to sacrifice some of the nonstick, stain-resistant convenience we’ve grown accustomed to, and avoiding (to the best of our ability) purchasing items made with forever chemicals. Rather than passing the burden on to future generations, we can each take responsibility for our collective past mistakes, overcome our natural human tendency to prioritize convenience and profit over care and concern for humanity, and make personal changes toward a better future for all. We can pay it forward and pay it now by treating others as we’d like to be treated.

Navigating a Toxic World

It’s easy to ignore dangers we can’t see, especially when the effects aren’t immediately obvious. Yet environmental pollutants quietly affect us in alarming ways.

But it’s not too late. According to science writer Julian Cribb, change is possible: “If consumers demand safe, healthy, green products, and are willing to pay industry a little more to make them safely, we can cleanse our planet within a generation and save countless lives.”

The catch is that it requires, from each of us, a different way of thinking. Although we can’t avoid all the environmental chemical hazards in our lives, we can each start with tiny steps toward better stewardship. Here are some things to consider:

- Be an informed consumer. Read widely and choose foods and goods that reduce human impact on the environment, thereby supporting conscientious farmers and producers while guarding your health and that of your family.

- Research your personal care and cleaning products, plastic containers, and toys. Because you can’t always know where your food comes from, choose a wide variety to reduce the chance of high toxin intake from a particular source, and avoid harmful products as much as possible.

- Choose natural fabrics and materials whenever possible for clothing, food preparation and storage, furnishings, and floor coverings, and avoid (or consider replacing with safer options when your budget permits) those that are chemically treated to resist stains, sticking, wrinkles, water, flames or fungus.

- Dust often with damp mops or cloths, and open windows when practical. Ventilation helps remove airborne toxins.

- Talk about the issue with others; raising awareness and educating ourselves is a critical step toward changing our habits and behaviors.

Avoiding toxic chemicals may seem like a futile task. It would be impossible—and terribly expensive—to remove all health hazards from our lives, but we can each do something. Choosing options that may be less convenient today but are safer and better for tomorrow is a challenge. As legislation and trends change, we can stay educated by checking the websites of consumer protection agencies.

One of the most important things we can do is to teach our children about toxins. Teach them how to think, research and learn for themselves—an important life skill. The future belongs to the next generation. As we work to clean our own environment today, giving them these survival tools will go far toward a cleaner, greener tomorrow.