Colonialism’s Painful Legacy

Confronting the Past in Hopes of a Better Future

Until we come to terms with the ugliest aspects of the colonial past, a more equitable world will remain out of reach.

In June 2022, nearly 17 million people took active part in celebrating Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee—the 70th anniversary of her ascension to the British throne. Media coverage showed the streets filled with well-wishers even as millions more watched the festivities from home. This, after all, was Britain’s longest-reigning monarch ever—a sovereign widely respected for her dedicated service and her unflagging sense of duty.

But as the celebrations unfolded, not everyone was looking at the monarchy in a positive light. In fact, in various places around the world, an opposing sentiment has been growing for some time.

In March, for example, three months before the official Jubilee festivities got underway, Prince William and his wife, Catherine, were on a tour of Belize, Jamaica and the Bahamas to cement a connection with the Crown. Some locals in each of the three countries saw the young royals as the face of an institution that promoted, supported and enabled colonialism, and thus as a link to land disputes and alleged atrocities committed by British colonizers.

An open letter from a Jamaican human rights coalition known as the Advocates Network expressed their concerns: “We are of the view that an apology for British crimes against humanity, including but not limited to, the exploitation of the indigenous people of Jamaica, the transatlantic trafficking of Africans, the enslavement of Africans, indentureship and colonialisation, is necessary to begin a process of healing, forgiveness, reconciliation and compensation.”

There can be no doubt that the various colonial and African powers engaged in the slave trade committed grave injustices against the human beings they abused so readily.

Human Capital

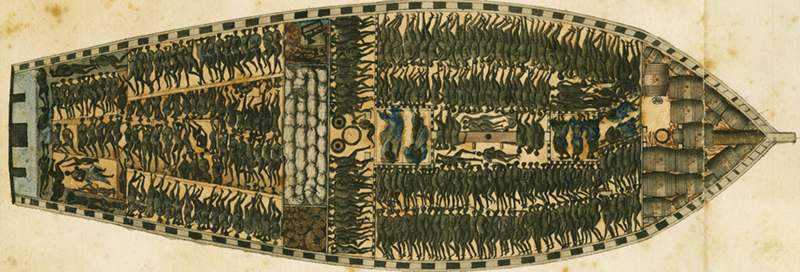

Understanding the cruelty inherent in the transatlantic trafficking of Africans provides helpful context, and to that end, a picture is worth a thousand words. Diagrams show hundreds of captives tightly crammed into slave ships. Captains made sure to use every bit of available space on the lower decks with the goal of maximizing profit from their human capital.

A 1770 illustration depicts the slave deck of the Marie Séraphique, a ship built specially for the transatlantic slave trade. The vessel, whose length was 20.5 meters (about 67 feet), completed six voyages, each time transporting an average of more than 350 enslaved Africans.

Historian and Santa Clara University professor Anthony Hazard, in a TED-Ed video titled “The Atlantic Slave Trade: What Too Few Textbooks Told You,” explains: “As for the slaves themselves, they faced unimaginable brutality. After being marched to slave forts on the coast, shaved to prevent lice, and branded, they were loaded onto ships bound for the Americas. About 20 percent of them would never see land again. . . . The lack of sanitation caused many to die of disease, and others were thrown overboard for being sick, or as discipline. . . . Those who survived were completely dehumanized, treated as mere cargo. Women and children were kept above deck and abused by the crew, while the men were made to perform dances in order to keep them exercised and curb rebellion.”

Although their human cargo was insured, ship captains knew their losses wouldn’t be covered if captives died of natural causes, such as disease, while aboard the ship. The fact that drowning was covered served as motivation to cast the sick overboard if it appeared that their illness might be terminal.

The Atlantic slave trade involved not only the United Kingdom but also Spain, Portugal, Brazil, the Netherlands, the United States, France, Denmark, and various African kingdoms that betrayed their own people for profit. An estimated 12.5 million Africans were taken from their homelands to the Americas; about 20 percent died en route. For the roughly 10 million who survived, the humiliation would prove to be continual and multigenerational, with no hope of emancipation. They endured squalid conditions, being sold at slave markets, having all aspects of life controlled by a slave master who determined, among other things, whether and whom an enslaved person could marry. Offspring born to slaves were immediately consigned to a life of servitude themselves and could be separated from their families and sold to other slave masters.

Between 1803 and 1836, the transatlantic slave trade was officially abolished by one nation after another. But that didn’t change underlying attitudes nor end the effects of slavery. In the southern United States, slaves weren’t effectively granted their freedom until 1865. Even then, the word freedom overstates the reality. During the post–Civil War Reconstruction Era, southern states, beginning with Mississippi, enacted “black codes” to regulate the behavior of the newly emancipated. For example, anyone could arrest an able-bodied Black person for vagrancy if they simply wandered or strolled in a leisurely manner. The practice of “convict leasing” (allowing prisons to hire out prisoners as cheap—or free—labor) encouraged the widespread arrest of “vagrants,” making convict slaves out of men who had only recently gained nominal freedom.

“Crafted to ensnare Black people and return them to chains, these laws were effective; for the first time in U.S. history, many state penal systems held more Black prisoners than white—all of whom could be leased for profit.”

Even as black codes were phased out, “Jim Crow” segregation laws took their place across the South. A hundred years after emancipation, African Americans were still fighting for many of the basic rights enjoyed by other people, including the right to vote. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1965 legislatively overturned segregation laws, long-standing racial bias had become systemic. It’s difficult to overcome the effects of imprisoning generations of men and crippling their families. And incidents such as the 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery, an African American who was chased down by three white men in pickup trucks, seem like eerie vestiges of the old vagrancy law. Arbery was out jogging, which oddly suggested to his assailants that he was up to no good and that they should make a citizen’s arrest. When Arbery resisted, they shot and killed him.

The fact is that unless nations and communities actively identify, acknowledge and root out the modern-day inequities that are a legacy of our shared colonial history, they will continue to operate—sometimes subtly, sometimes less so.

This is why such groups as the Advocates Network exist and why they address letters to members of the royal family and others in positions of influence. An apology would seem to be a reasonable starting point in acknowledging what took place and its ongoing effects.

Columbia University Ombuds Officer Marsha L. Wagner, in “Elements of an Effective Apology,” calls it “a powerful means of reconciliation and restoring trust.” Wagner underscores that an effective apology will include statements that demonstrate an understanding of the exact nature of the offense, recognition of accountability, acknowledgment of the pain caused, a judgment about the offense, a statement of regret and—importantly—a statement of future intentions. In other words, a sincere and effective apology needs to be a precursor to change—to doing things differently and trying to right some of the wrongs.

Colonialism’s Broader Context

A few months before the Jamaican group protested the queen’s Jubilee celebrations, the former colony of Barbados removed the British monarch as its head of state and chose to become a republic. In a show of support and affirmation of the will of the Barbadian people, King Charles III (then the crown prince) was on hand in November 2021 to offer well wishes. Before Barbados, the last nation to remove Queen Elizabeth as head of state was Mauritius, in 1992. But in the aftermath of her death, it’s likely that other members of the Commonwealth may follow suit.

Of course, in one of the most famous acts of throwing off the monarchy, the American settlers declared their independence from England in 1776. But that didn’t stop the new nation from continuing the colonization process on its own.

American sociologist Crystal M. Fleming notes: “The United States and many of the countries throughout the Americas were built on a special type of colonization called settler colonialism. This type of colonialism occurs when a group decides to move to another part of the world, remove the native population, and establish its society on that land.” Beyond the Americas, examples of removing or displacing Indigenous peoples include the colonization of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, among others.

“American settler colonialism evolved over the course of three centuries, resulting in millions of deaths and displacements, while at the same time creating the richest, most powerful, and ultimately the most militarized nation in world history.”

“Why did the European colonizers want Native land in the first place?” Fleming asks, observing that greed was a prime factor. They traveled the globe “in search of gold and other precious materials that could enrich their kingdom back home.”

As already mentioned, some of the “precious materials” they sought were Indigenous people who could be exported from Africa and forced to work for little or nothing in New World colonies. But the subjugation of local populations for the sake of exploiting a nation’s resources was also widespread in regions such as South and Southeast Asia. India, Myanmar (Burma) and Indonesia are notable examples.

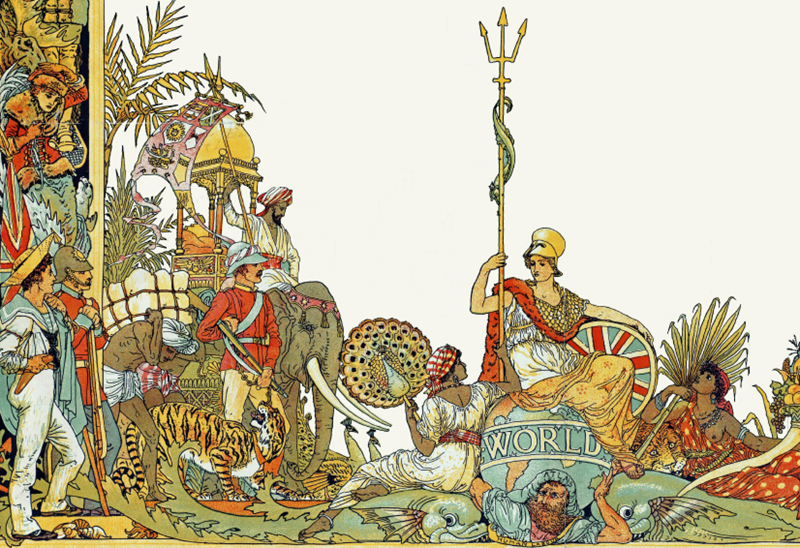

Detail from the border of an 1886 map of the British Empire as it existed at that time.

Fleming, focusing on the colonialism of white Americans, remarks that their role in government enabled them to create, pass and implement legislation to their own benefit at the expense of minority communities. Greed—that excessive and selfish desire to acquire something (whether wealth, power, food, resources or anything else, usually in excess of actual need)—has long been a factor in the behavior of those in power. But it’s a violent force that any human being, from any nation, at any point in history is susceptible to.

Throughout history, colonizers were quite often white people of European ancestry. On the other side, in the case of settler colonialism, were Indigenous peoples—usually portrayed as less advanced. Their comparative lack of power made them easier to overcome and to set apart as the colonized Other. Australian historian Patrick Wolfe, who pioneered the study of settler colonialism, explains that “settler colonies were (are) premised on the elimination of native societies. . . . The settlers come to stay—invasion is a structure not an event.”

Manifest Destiny

The desire for physical goods, wealth and land, all of which tend to enhance a nation’s power, drive colonization of all types. But alongside this predatory mindset was the American concept of Manifest Destiny—as Fleming notes, “the belief that the people of the United States were destined [by Providence, or God] to expand across the continent and displace the Indigenous groups living here.”

White settlers, championed by white politicians, soon began to proclaim the inevitability of expanding their territory “from sea to shining sea.” On the basis of racist ideas about white superiority, the settlers concluded that they had a moral right to take territory from the Indigenous peoples.

This was a popular sentiment in the 19th century, in particular after US president Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase of 1803. That transaction with France nearly doubled the size of the United States at a cost of approximately $15 million (about $350M in today’s money), or four cents (just under a dollar today) per acre. It was now the white Americans’ duty to settle what they considered to be their land, though the Indian tribes had never sold or ceded any of it to the French or any other colonial power. In effect, the American government bought the supposed right to unilaterally and forcibly displace the native inhabitants in order to develop and settle the land themselves. Promises to provide them with what they would need in order to resettle elsewhere went largely unfulfilled.

“The U.S. government forced many Native Americans to give up their culture and did not provide adequate assistance to support their interconnected infrastructure, self-governance, housing, education, health, and economic development needs.”

Wolfe calls this forced separation of Natives from their land and culture ethnocide: “I use this term in this context because, as opposed to genocide, which suggests physical extermination, ethnocide is directed against collective identity, which does not preclude leaving individuals alive.”

Others, however, argue that this is in essence genocide. Indeed the United Nations, in its own discussion of the term, specifies that genocide includes much more than the outright murder of another people. The word was coined by Polish lawyer Raphäel Lemkin in his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The etymology is fairly straightforward: geno-, from genos, the Greek word meaning “to give birth” (referring to race or kind); and -cide, from the Latin for “killing.” Lemkin used it primarily to describe the systematic murder of Jews in the Holocaust but acknowledged a broader application.

The Selfish Pursuit of Power

When the Nazis employed their Blitzkrieg tactics at the beginning of World War II, they took over much of mainland Europe. They sought land, or Lebensraum: additional space in which to live and grow. Having declared that the Aryan people were superior to others, including not only Jews but also Poles, Slavs, Roma, those of African descent, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, the mentally or physically disabled and others, Hitler had no qualms about ridding Europe of them all. It was a form of settler colonialism intended to allow the German nation to expand and become militarily and economically powerful after its humiliating defeat in World War I.

King Charles III’s grandfather, George VI, understood that self-interest was central to the Nazi approach. At the outset of World War II, on September 3, 1939, he said in a radio address to the British people, “For the second time in the lives of most of us we are at war.

“Over and over again, we have tried to find a peaceful way out of the differences between ourselves and those who are now our enemies. But it has been in vain. We have been forced into a conflict. For we are called, with our allies, to meet the challenge of a principle which, if it were to prevail, would be fatal to any civilized order in the world.

“It is the principle which permits a state, in the selfish pursuit of power, to disregard its treaties and its solemn pledges; which sanctions the use of force, or threat of force, against the sovereignty and independence of other states.”

Today the war between Russia and Ukraine also illustrates “the selfish pursuit of power” that King George described. On Friday, September 30, 2022, Reuters published an article describing the latest development in the conflict at that time:

“A defiant Vladimir Putin proclaimed Russia’s annexation of a swathe of Ukraine in a pomp-filled Kremlin ceremony, promising Moscow would triumph in its ‘special military operation’ even as he faced a potentially serious new military reversal.

“The proclamation of Russian rule over 15 percent of Ukraine—the biggest annexation in Europe since World War Two—was roundly rejected by Ukraine and Western countries as illegal.”

The net effect of the lust for land, power and dominion over others—in essence a colonial mindset—is the suffering of fellow human beings. But although we may read about specific, egregious examples of that approach in our history books, it’s an age-old, universal human problem.

“Those conflicts and disputes among you, where do they come from? Do they not come from your cravings that are at war within you? You want something and do not have it; so you commit murder. And you covet something and cannot obtain it; so you engage in disputes and conflicts.”

King George VI saw the dangers inherent in one nation or leader attempting to overthrow the life and freedom of other peoples: “Such a principle, stripped of all disguise, is surely the mere primitive doctrine that ‘might is right’; and if this principle were established throughout the world, the freedom of our own country and of the whole of the British Commonwealth of Nations would be in danger. But far more than this—the peoples of the world would be kept in the bondage of fear, and all hopes of settled peace and of the security of justice and liberty among nations would be ended.”

What the king’s speech omitted, however, was any recognition of the role his forebears had played in subjugating and exploiting the peoples of other lands in their own colonial quest for land and power. It’s often easy to recognize how the actions of others might bring fear and jeopardize “all hopes of settled peace” among nations. Seeing how we—our own supposedly civilized societies or nations—may be guilty of similar injustices, whether past or present, tends to be more difficult.

We’re dependent on leaders to guide the path of the nations we each call home. Clearly, if our leaders fail to recognize the double standards that mark all of human history, and if they fail to stop the exploitation of Other for their own national or personal benefit, then nothing will change. Only when human beings—all of us—rethink the idea that “might is right” and replace that approach with a genuine concern for others—all others—and their needs, will we finally see an end to humankind’s endless cycle of violence, oppression, destruction and suffering.

As the world moves on after the death of Britain’s longest-reigning monarch, and as a new chapter begins with a new king who will no doubt be asked to confront fallout from our collective colonial past, perhaps it’s an opportune time to reevaluate our personal motivations and to exhibit, on an individual level, a commitment to service rather than oppression and to compassion rather than acquisition.