As It Was From the Beginning?

“Leaders and kings of the barbarians . . . were capable of conceiving of some mighty king of kings greater than themselves and giving a real law for all men, and they were ready to believe that elsewhere in space and time, and capable of returning presently to resume his supremacy, Caesar had been such a king of kings. Far above their own titles, therefore, they esteemed and envied the title of Caesar. The international history of Europe from this time henceforth is largely the story of kings setting up to be Caesar and Imperator.”

A wise man once noted that “a generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever” (Ecclesiastes 1:4, New American Standard Bible throughout). The earth stays, we go. Yet despite our transient nature in comparison to the earth that sustains us, human civilization has survived. It has been that way from the beginning.

Can we therefore expect, as we probably do, that it will always be so?

Human civilizations began thousands of years ago when people started to organize themselves into settlements under common rule in common strongholds. Those settlements were established to provide security from predators, both animal and human, and to provide adequate food, water and shelter. However, in the very beginning, according to the account of creation in the book of Genesis, humanity was not in need of protection from other men or from the animals. Nor was it without adequate life-sustaining necessities.

In fact, the creation with which we are familiar was the end result of a process of restoring order to an earth that had been reduced to a state of chaos, according to Genesis 1:2. The last verse in that chapter, together with the next chapter, tells us that once order had been restored and a suitable habitat had been prepared to support life, the first human beings dwelt peacefully with their Creator, their environment and the animals. This harmonious balance was disturbed when our parents, Adam and Eve, decided at the urging of one represented in the story as a serpent that they would discern for themselves, apart from the Creator, what is good in life and what is evil.

At that instant, the integrity of their world was compromised. Genesis 3 records the introduction of a spirit different from the one present at the completion of the creation. The most significant and immediate consequence was the loss of a secure domain for humanity. People would now toil to make the land produce, and struggle to find protection from an environment that once nurtured them. And later, when Adam’s son Cain murdered his brother, Abel, there was for the first time an awareness that human beings would need protection from each other as well. Chapter 4 tells us that Cain’s deed resulted in his expulsion from society and in the deprivation of his livelihood. To protect himself and provide for his survival, he built the first city—humanity’s earliest attempt at a common settlement under common rule.

Human autonomy was the underlying motivation for pe-Flood civilization and for every society since.

Human autonomy was the underlying motivation for pre-Flood civilization and for every society since. The result was civilizations built on a foundation of fear for survival and the need for self-protection.

Genesis 6 tells us that the antediluvian world that began with Adam became so corrupt that it was destroyed. Humanity, barely spared from extinction, set out to rebuild civilization. In fact, Noah’s great-grandson Nimrod, in the second generation after the Flood, succeeded in creating a kingdom centered at Babel (Genesis 10:8–12). The well-known symbol of Nimrod’s rule was the famed Tower of Babel, a monument to human self-will and the desire for sovereignty and dominion over the earth. Like pre-Flood society, however, Nimrod’s civilization-building came to a sudden end (Genesis 11:1–8), and the tower was abandoned unfinished. But what remained has exerted its sway on human society ever since; the spirit that animated Adam, Cain and Nimrod continued unabated. So many other kingdoms, empires and civilizations followed, every one of them motivated by the same mindset.

A King and His Dream

Among this world’s civilizations were four empires whose influence reached far beyond the territory they dominated and the age in which they ruled. Spawned from fledgling nations or city-states, their influence can be seen and felt even in our world today. They included the Neo-Babylonian Empire (ca. 625–539 B.C.), the Medo-Persian Empire (558–330 B.C.), the Greco-Macedonian Empire (from 333 B.C.), and the Roman Republic and Empire (241 B.C.–A.D. 476).

The histories of these empires, surprisingly, were anticipated in a dream that Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, had in the second year of his reign. In that dream, recorded in Daniel 2, he saw a great image with a head of gold, chest and arms of silver, belly and thighs of bronze, legs of iron, and feet and toes of iron mixed with clay. The biblical account states that Nebuchadnezzar was troubled by the dream, but that after he awoke he couldn’t remember it. His search for someone who could tell him both the dream and its meaning led to the young Jewish wise man, Daniel. On God’s behalf, Daniel revealed the matter to Nebuchadnezzar.

The head of gold, he said, represented Babylon, the finest of the kingdoms. And he, Nebuchadnezzar, was a “king of kings.” The chest and arms of silver symbolized the Medo-Persian Empire, and the belly and thighs of bronze the Greco-Macedonian. The fourth kingdom, the Roman Empire, was symbolized by the legs and feet of the great image. The legs of iron signified the strength of this regime. The feet and toes, a combination of iron and clay, revealed another aspect of its character: its strength would be compromised by internal divisions.

The image that Nebuchadnezzar saw was a single statue with one head. Though there were four individual empires, they had a continuity of purpose. This is the story of humanity’s continuing quest for self-rule and dominion over the earth in civilizations apart from the Creator. Although much of the story represented by the great image is now past, what remains is future for us.

Elsewhere in Scripture are prophecies that highlight some of the distinctions in the character, nature and development of these empires. See, for example, Daniel 7. What is revealed is, in part, a progression from a dominant centralized power—Babylon—to other powers of the same motivation: Medo-Persia, Greco-Macedonia and Rome. The Roman Empire is described as the one that will crush and break the others and then subsume them. And although politically divided and at the end of its life partly strong and partly brittle, it is to continue to exert its influence widely until such time as God establishes a dominion that will never end (Daniel 2:41–44; 7:9–14).

They Came, They Went—Or Did They?

While the first three empires came and went, Rome’s story is different. In its ascent and through most of its rule, the Roman Empire, true to the prophecy, “broke” many nations and peoples. At the zenith of its power, that empire stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Caspian Sea and from the Caucasus Mountains to North Africa.

While the first three empires came and went, Rome’s story is different.

Rome dominated through military and political conquest that was often unrelentingly cruel. But its method of subduing others foreshadowed its own political division, as did its policy of pluralistic tolerance for other cultures. In addition, the size and complexity of the empire and the changed role of the military and the emperor after the death of Marcus Aurelius were to produce a fracturing from which it never recovered. The western empire was centered at Rome, where the senate resided. The eastern empire was established at Byzantium (Constantinople) and was formally recognized by Emperor Diocletian in about A.D. 286. By 293 each capital had its own “Augustus,” who was supported by his own Caesar. At the head of it all was the Augustus who ruled by the grace of god—a sort of “king of kings.” As Diocletian envisioned it, the division was permanent, and in time the empire that once seemed unassailable appeared to have collapsed entirely.

In the 1921 edition of his compendious and magisterial Outline of History, Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind, H.G. Wells wrote that “while the smashing of the Roman social and political structure was thus complete, while in the east it was thrown off by the older and stronger Hellenic tradition, and while in the west it was broken up into fragments that began to take on a new and separate life of their own, there was one thing that did not perish, but grew, and that was the tradition of the world empire of Rome and of the supremacy of the Caesars” (emphasis added).

The motivation to preserve that tradition, Wells said, was that “leaders and kings of the barbarians . . . were capable of conceiving of some mighty king of kings greater than themselves and giving a real law for all men, and they were ready to believe that elsewhere in space and time, and capable of returning presently to resume his supremacy, Caesar had been such a king of kings. Far above their own titles, therefore, they esteemed and envied the title of Caesar. The international history of Europe from this time henceforth is largely the story of kings . . . setting up to be Caesar and Imperator (Emperor).”

“Removed from the possibility of verification, the idea of a serene and splendid Roman world-supremacy grew up in the imagination of mankind.”

Wells went on to note that when the reality of the Roman Empire was destroyed in the fifth century, the legend of what it was had freedom to expand. “Removed from the possibility of verification, the idea of a serene and splendid Roman world-supremacy grew up in the imagination of mankind.” The “Caesaring” of Europe, as Wells referred to it, began almost immediately. Initiated in the eastern or Byzantine empire, it expanded to the west with Justinian I and continued until after the Great War of 1914 to 1918. That conflict brought to an end the reign of at least four Caesars: the German kaiser (from the Latin caesar), the Austrian kaiser, the Russian czar (also from caesar) and the czar of Bulgaria. It was the defeat of Hitler and the axis powers in World War II, however, that seemed to subdue the tradition of a serene and splendid world empire and the supremacy of a caesar, a king of kings, to rule it.

The Empire That Wouldn’t Die

The Roman Empire, by virtue of the legend and tradition of the Pax Romana, captivated the world in one manner or another for nearly two millennia. This enduring quality—the will to reinvent what people believed the Roman Empire to be—was shown to Daniel. Those details are also recorded in the seventh chapter of his book.

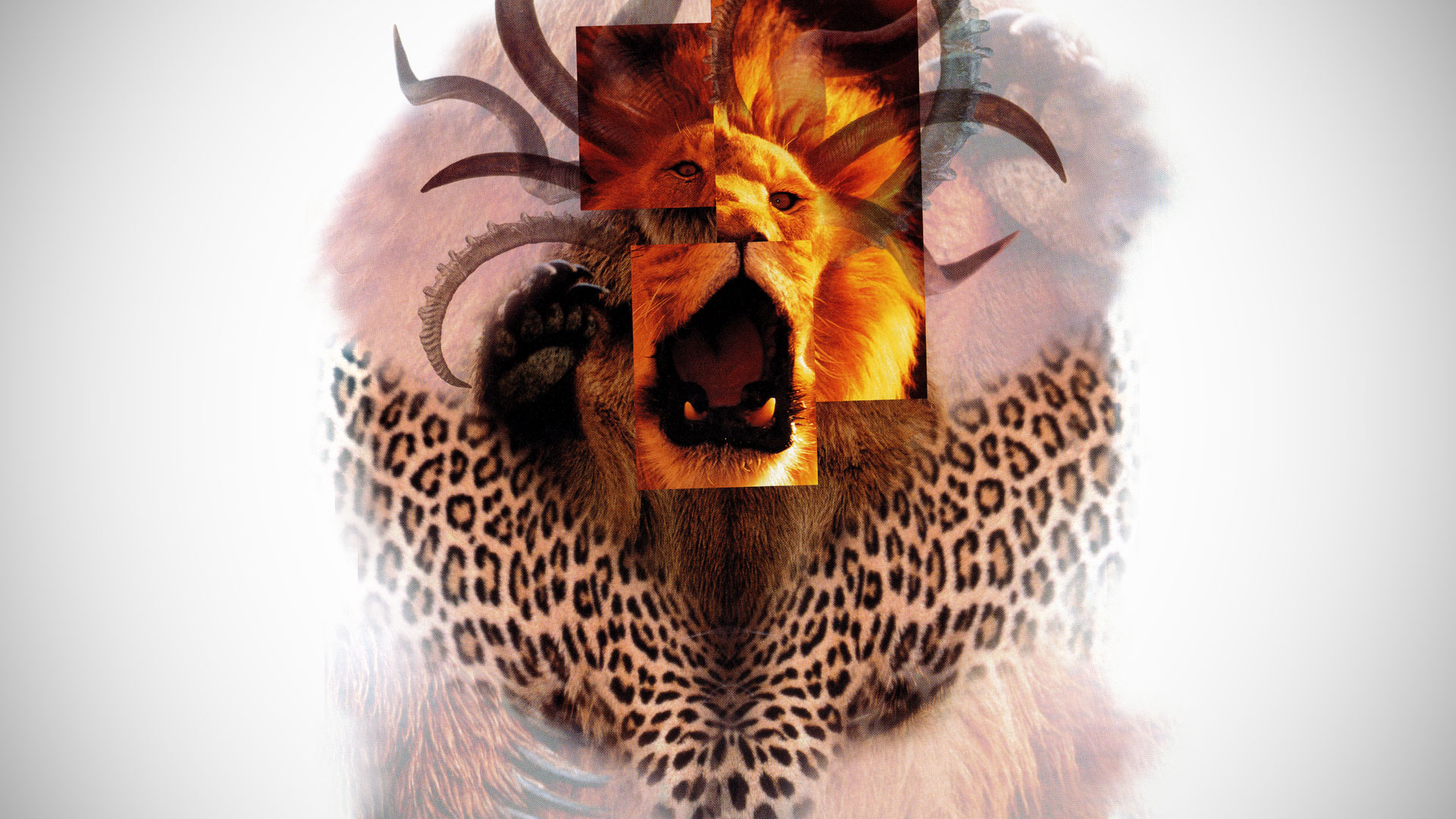

Daniel saw the four powerful world empires of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream now depicted as animals. A lion correlates with the head of the great image, Babylon. A bear corresponds to the chest and arms of silver, Medo-Persia; and a leopard to the belly and thighs of bronze, Greco-Macedonia. The legs of iron and the feet of the image, the Roman Empire, are depicted by a fearsome animal very different from the others. This “dreadful and terrible” beast has 10 horns.

In the New Testament book of Revelation, chapters 13 and 17 record a similar vision given to the apostle John at the close of the first century. It is a confirmation of both Nebuchadnezzar’s dream and Daniel’s vision of humanity’s final attempt to establish its own “serene and splendid” world empire, with added details about its nature, character and structure. The seven heads of Revelation 17:3 and the 10 horns of Daniel 7:7 represent efforts to reinvent the world empire of Rome down through time until it is replaced by the kingdom of God.

So far those efforts to reignite the legend of Rome have produced only short-lived and much diminished versions of the original empire. But do the legend and tradition of the world empire of Rome still have life?

The question arises because within the geographic area formerly occupied by the Roman Empire, the increasingly influential European Union (EU) now resides. As the world’s largest economy, it is a growing political entity with the potential to match the world’s only superpower, the United States. Although it is still a work in progress, many of the nations of Europe have, in the last half century, forged a significant union. So some observers wonder whether the new Europe will span the Eurasian landmass as the original Roman Empire once did. Not a few in Europe, particularly those banging on the EU’s door to be let in, hope to see Charles de Gaulle’s vision of Europe come to pass—a Europe that extends from Portugal to the Ural Mountains. It is a vision reminiscent of the Roman Empire’s European reach.

At the center of the debate about what Europe will become is the question of whether the EU should pursue a wider, weaker, essentially economic federation, or a deeper, stronger political union. The question may be academic in the final analysis. The EU’s 15 member nations are a diverse group whose national, political, economic, cultural and ethnic differences, not to mention past histories, argue against a truly strong political confederacy. Its 12 candidates for entry, mostly from the East, only add to the diversity after 45 years under communist rule.

Strong Yet Weak

These factors, and the complex, often convoluted political processes of the EU, seem to mirror the details of Daniel’s prophecy specifying a partly strong, partly fragile world power. Those feet and toes—humanity’s final attempt at self-rule—are characterized as iron mixed with clay: brittle. Verse 43 of Daniel 2 further interprets these symbols by telling us that one of the attributes of this power is that its constituent parts will “combine with one another in the seed of men; but they will not adhere to one another, even as iron does not combine with pottery.”

The current reshapers of Europe may not be driven by the “idea of a serene and splendid Roman world-supremacy,” as Wells put it, but the union they are creating today is in continuity with the tradition represented by Nebuchadnezzar’s great image. Eventually the final superpower will become a geopolitical force with global influence that will exceed anything that ancient Rome enjoyed at the height of its power. It will become a world empire like no other before it, exercising influence over all nations (Revelation 13:7–8).

According to Revelation 13 it will possess attributes reminiscent not just of Rome but of all the powerful empires that preceded Rome. A composite of the animals of Daniel 7, it will be like the leopard, with the feet of the bear and the mouth of the lion; that is, Greco-Macedonia, Medo-Persia and Babylon combined (verse 2). The text does not specifically interpret the meaning of this image, so all that it is intended to convey is not clear. However, this prophecy and its parallel prophecies clearly speak to the fact that the legend and tradition of the world empire of Rome is very much alive and in continuity with the mind from which it sprang: Babylon.

The end of this world power will come when it is given by its leaders to another with a beastlike spirit, as Revelation 17:17 states. And although unseen, it is the same spirit that has ruled human civilizations since Adam. It alone accounts for the continuity in mind and purpose of the four empires depicted by the great image of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. The time will come when the spirit behind the beast is exposed (Revelation 18 and Ezekiel 28:18–19), expelled (Revelation 20:1–3) and replaced by a very different kind of world empire, the kingdom of God (Revelation 21).

A Legend in His Own Mind

In retrospect, it is clear that what God showed Nebuchadnezzar in his dream was a vision of how he imagined himself: a king of kings capable of constructing what no man had ever built—a splendid and serene world empire capable of articulating a law for all humanity.

What God showed Nebuchadnezzar in his dream was a vision of how he imagined himself.

Nebuchadnezzar’s view of a magnificent human civilization, as represented by the great image in his dream, is very different from the one the prophet Daniel and the apostle John saw. That’s because they saw beyond the image to the heart of human civilization. They understood that whether it was Babylonian, Medo-Persian, Greco-Macedonian or Roman, it was beastlike and would remain so until the true King of kings would establish His Father’s kingdom on this earth.

The setting up of that kingdom represents the restoration of what humanity lost in the Garden of Eden and has been striving to recreate ever since: a truly serene and splendid world government with one law for all humanity. At that time, the ebb and flow that has characterized human civilization from the beginning will cease. The earth and the heavens, which to us seem so permanent, will be replaced by a new creation, a home for righteousness, peace and justice (2 Peter 3:3–13).

We err if we believe that all things will continue just as they have from the beginning.