Let Us Rise Up and Build

The Legacy of Nehemiah

Under continuous opposition, Nehemiah, governor of the Persian province of Judah, rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem in just a few weeks. His work of rebuilding the moral core of Judah’s people took much longer.

Nehemiah, cupbearer to the Persian emperor Artaxerxes, was serving in the ruler’s winter palace at Susa. Along with many other Jews, he became part of the diaspora when Cyrus liberated them from their Babylonian captivity in 538 BCE. In the ensuing years, they had spread throughout the empire. Now, almost a century later in 444, Nehemiah received a visit from his brother Hanani, who had come from Jerusalem.

So begins Nehemiah’s memoir, which complements the account of Ezra the priest. Nehemiah learned that, several years after Ezra’s return to Jerusalem, the city’s wall and gates were still in a state of disrepair. He was perhaps aware that under Ezra the wall-building had been stopped by the king’s command because of complaints from local enemies of the Jews (Ezra 4:12, 17–23).

The news greatly affected Nehemiah, causing him to fast and pray for forgiveness for all of Israel. He recalled that Moses had prophesied the ultimate outcome of Israel’s departure from God—captivity in foreign lands—but also that repentance would bring them back into God’s favor and to their land. He concluded his prayer by asking for mercy “in the sight [or eyes] of this man”—the king whom he served (Nehemiah 1:4–11; Deuteronomy 28:64; 30:1–5). Perhaps he would be willing to intervene and resolve the problem of Jerusalem’s broken defenses.

Four months later, Nehemiah had the opportunity to speak with Artaxerxes about the matter. The cupbearer’s downcast appearance caused the king to ask the reason. The opportunity before Nehemiah made him both afraid and extremely diplomatic. Without naming Jerusalem, he mentioned that the city of his ancestors, their tombs, its walls and its gates lay in ruins. For this reason, he was very sad.

Artaxerxes, with the queen alongside, asked what he could do. Nehemiah boldly asked for permission to go to Jerusalem with letters from the king guaranteeing safe passage through the provinces of the Trans-Euphrates region and, once in Judah, access to building materials. The king granted his requests, providing an armed guard and sending him back to the Jewish capital, where he would become governor.

Nehemiah’s arrival caused the local opponents of the Jews deep distress when they learned that his purpose was to help the Israelites (Nehemiah 2:1–10).

Nehemiah’s Work

The account continues with details of the reconstruction work Nehemiah accomplished. First he surveyed the broken walls by night and went about organizing their repair, along with repair of most of the city’s gates. Other structures, including towers and pools, were renovated. Nehemiah enlisted the help of a cross section of the Jewish population, including priests, artisans, district rulers, Levites and merchants. Many lived within the walls, but others came from nearby towns to help (3:1–32). They carried out the work despite opposition, accusation, scorn and ridicule from Judah’s surrounding adversaries, led by the Samaritan Sanballat to the north, the Ammonite Tobiah to the east, and the Arab Geshem to the south (2:19; 4:1–3, 7–8).

“It has long been recognized—and is today universally agreed—that substantial parts of the Book of Nehemiah go back to a first-person account by Nehemiah himself (or someone writing under his immediate direction).”

A constant theme in Nehemiah’s memoir is his positive attitude and reliance on God in the endeavor (4:4–6). As a result, on this occasion the enemies were temporarily thwarted, and the Jews were soon able to build about half the wall’s height.

But then another attempt to prevent the work came from the same people. This time they planned an attack, helped by men from Ashdod to the west. Once again Nehemiah prayed, and then he set a 24-hour watch (verses 7–9). When the adversaries heard of his strategy, they decided not to attack. Work on the wall continued, and ultimately, having languished for decades, was completed in 52 days (6:15).

Whereas this physical construction occupied only a fraction of Nehemiah’s time in Jerusalem, he spent the entire 12 years of his governorship dealing with the spiritual problems of his people.

Chapter 5 outlines one such difficulty that arose: fellow Israelites had been demanding interest on loans to buy grain in time of crop failure and mortgaging their land and children as slaves. Though the people’s greed and harshness toward the less fortunate angered Nehemiah, his resolution of these forms of oppression demonstrated his personal integrity, generosity and commitment to the law of Israel’s God.

Despite more conspiracy and subterfuge from Sanballat, Geshem and Tobiah (6:1–14), the whole project was completed with the hanging of the city gates (7:1). Nehemiah then appointed two leaders over Jerusalem: his brother Hanani, and Hananiah, the trustworthy overseer of the fortress. He also proposed a registry by family of those who had come back from Babylon. His intent was to locate purely Jewish people and repopulate Jerusalem, which still had few residents and lacked rebuilt houses. Nehemiah found the list of those who had returned under Zerubbabel more than 90 years previously, and presumably revised it as he matched up their descendants (verses 2–72; see also Ezra 2).

Rebuilding the Wall of Jerusalem, engraving (1886, artist unknown)

Ezra Reads the Law

Scholars have noted that what appears next, in Nehemiah 8, could be out of place chronologically and would fit better in Ezra’s account of events following his return 13 years earlier. He is suddenly introduced into the narrative by a third party. We don’t hear Nehemiah’s voice again until chapter 11 but instead that of a narrator who describes Ezra’s reading of the law before the assembled people and the keeping of some of the festivals of the seventh month (Nehemiah 7:73–8:18). Two chapters follow with a theologically driven purpose, as we’ll see.

Ezra had arrived in Jerusalem in the fifth month, just a few weeks before the third holy day season of the year, which would begin in the seventh month. As noted earlier, he had come to expound the law of God (Ezra 7:8–10). It makes sense that what is covered in Nehemiah 8—showing Ezra reading the law and encouraging the people to observe the first day of the seventh month, the Feast of Trumpets (Nehemiah 8:2–3, 8)—relates to the time just after Ezra’s arrival in Jerusalem.

Further, the people’s discovery that they needed to observe the Feast of Tabernacles later that month is most likely to have occurred just after Ezra arrived, not years later. It’s reasonable to think that, with Ezra teaching the law for 13 years prior to Nehemiah’s coming, the people would have kept the festival already. Indeed, as the narrator says, it was a unique moment, and one that surely would have occurred at the beginning of Ezra’s stay: “So the whole assembly of those who had returned from the captivity made booths and sat under the booths; for since the days of Joshua the son of Nun until that day the children of Israel had not done so. And there was very great gladness” (verse 17).

Nehemiah briefly appears as governor alongside Ezra (verse 9), but not again until several chapters later. Interestingly, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, the Septuagint, doesn’t include the word governor at this point, perhaps implying an edit to verse 9 in later Hebrew manuscripts. And an extrabiblical account of the event (1 Esdras 9:49) mentions Ezra but not Nehemiah. Further, it can be argued that the subject (“he”) in Nehemiah 8:10 can in context refer only to Ezra, followed as it is by a singular verb (“said”). Equally puzzling is that Ezra does not appear again until chapter 12. Taken together, this all suggests that chapter 8 is an anomaly in the story flow.

Bible scholars have arrived at no unanimous resolution of these chronological and editorial questions. Some believe that Nehemiah 8 has been transferred from an earlier version of the Ezra manuscript, where it stood between chapters 8 and 9. If this is so, what was the reason? A possible answer revolves around the intention of the final editor of Ezra-Nehemiah. If his purpose was to create not just a historical work but also an encouragement to greater fidelity and commitment among the returnees, then the order and nature of the materials could have been amended and/or created accordingly.

“Jewish tradition is clear in its opinion that these two works were originally one, and that they were to be regarded as separate from other books.”

As they stand, chapters 8–10 seem to form a specially purposed climax to the work of Ezra and Nehemiah to demonstrate the people’s renewed commitment to the God of Israel following their return. Consider that Ezra’s reading of the law could have coincided with the requirement to do so at the Feast of Tabernacles every seven years (Deuteronomy 31:10–13). This would then present an opportunity for repentance and renewal of their covenant with God.

In keeping with this possibility, Nehemiah 9 contains such a renewal in the form of extended praise and confession, led by the Levites. The absence of Ezra in the chapter supports the idea that this is part of a deliberately devised interlude. The lengthy prayer serves to remind the people of God as Creator, and of His favor toward Abraham, of their release from Egyptian slavery yet failure to keep God’s law, of their entry into the Promised Land, and of their sinful history and oppression under foreign powers up to that time. With this history in mind, they agreed to a renewal of a written covenant with God, sealed by their leaders.

The timing of this chapter might seem obvious from the opening verse: “Now on the twenty-fourth day of this month the children of Israel were assembled with fasting, in sackcloth, and with dust on their heads” (9:1). But there are reasons to doubt that this immediately follows the Feast of Tabernacles of the seventh month (8:18), which ended on the 22nd day.

First, the people’s mood is not joyous as would be expected following the festival, but somber and repentant. The seventh month is not specified, just a day of the month. The context of the chapter—the recognition that intermarriage with the people of the land was forbidden—fits better with the circumstances of Ezra’s time, when he had overseen the separation of unlawful marriages: “So all the men of Judah and Benjamin gathered at Jerusalem within three days. It was the ninth month, on the twentieth of the month; and all the people sat in the open square of the house of God, trembling because of this matter . . .” (Ezra 10:9). Four days later, they could have come together to formally repent as specified in Nehemiah 9:1.

With this understanding, the chapter then aligns with the events of Ezra’s earlier time, forming part of the editor’s effort to bring the renewal of Israel to a climactic ending rather than to create a chronological record.

The details of the agreement are specified in chapter 10. They include “an oath to walk in God’s Law”; prohibition of intermarriage with “the peoples of the land”; no commercial activity on the Sabbaths; observance of the sabbatical year regarding land rest and associated forgiveness of debt; an annual temple tax; a wood offering to provide for sacrificial offerings; and the donation of firstfruits and tithes. Additional regulations follow in respect of priests and Levites and the storage of tithes and offerings at the temple.

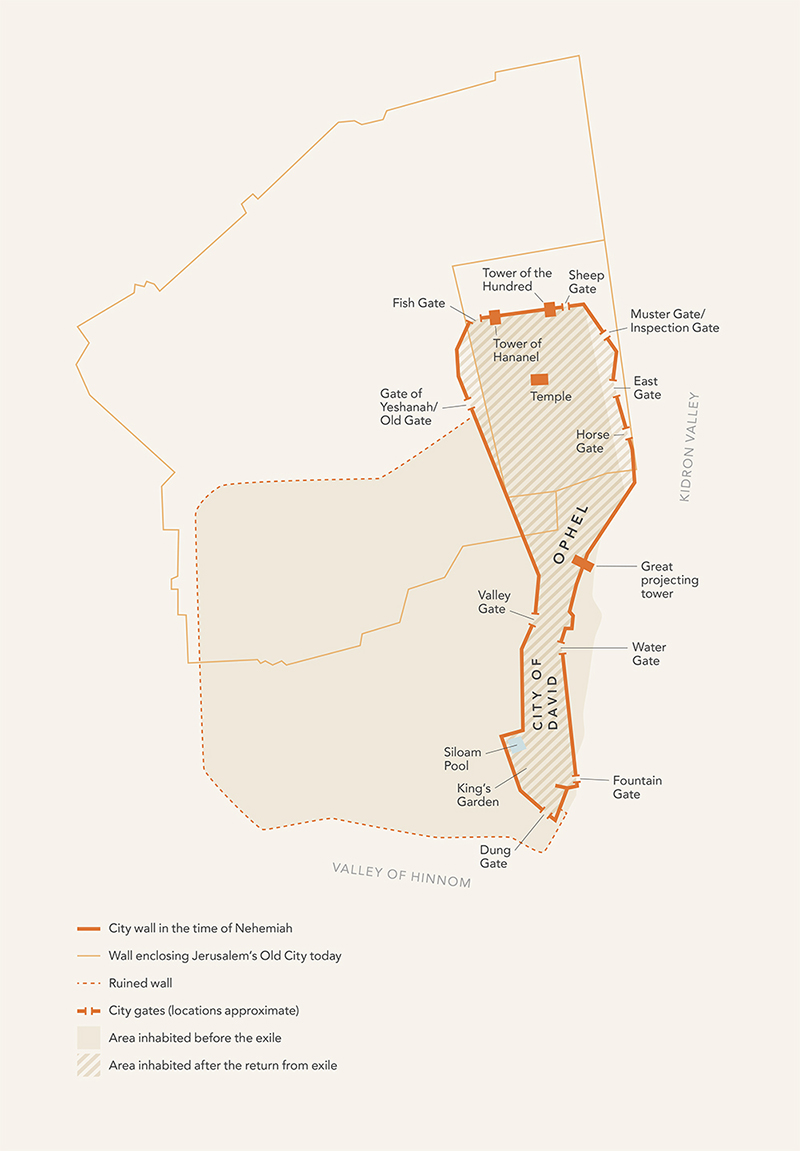

Jerusalem in Nehemiah's Time

Sources: The Bible Knowledge Commentary: Old Testament and New Testament Edition, edited by John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck (1983), The ESV Study Bible (Crossway Bibles, 2008).

Continuing Reforms

Chapter 11 resumes the discussion left off in chapter 7 about the repopulation of Jerusalem. Now provision is made for the leadership and a tenth of the returned exiles to reside in the city. Among them were some from the tribes of Judah and Benjamin, along with certain priests and Levites. The other cities of Judah were home to “Israelites, priests, Levites, Nethinim, and descendants of Solomon’s servants” (verses 1–4).

Chapter 12 details the genealogy of the priests and Levites and their roles, demonstrating uniformity with the traditions of the ancient united Israelite kingdom under David and Solomon. This leads to a description of the celebration that followed completion of the reconstructed city walls, where Nehemiah assembled the leaders. Then, to the sound of trumpets and other traditional musical instruments, two thanksgiving choirs proceeded along the walls in opposite directions, one led by Ezra and the other accompanied by Nehemiah. Meeting at the temple, they sang and gave thanks and sacrifices.

In conclusion, the author further emphasizes how the priests and Levites, singers and gatekeepers followed the rules laid down by David and Solomon with respect to the service of the temple. Again, this makes the point that the renewed society of the returnees aimed to recreate the kingdom of old. The funding for the centralized religious aspect of the reestablished society came from the entire population: “In the days of Zerubbabel and in the days of Nehemiah all Israel gave the portions for the singers and the gatekeepers, a portion for each day” (12:47).

The final chapter acts as a kind of coda to the history of the entire Ezra-Nehemiah reform project. Nehemiah’s introduction refers back to the great celebration day and the reading of the law with respect to prohibiting Ammonites and Moabites in the assembly. He then records that the Israelites separated themselves from the foreigners among them (13:1–3).

“This book underscores the importance of physical protection for God’s people in Jerusalem but, more importantly, it stresses the need for His people to obey His Word, not giving in to sin through neglect, compromise, or outright disobedience.”

This prefaces the unusual case of Tobiah, Nehemiah’s Ammonite enemy, who with his son had married into Jewish aristocratic families (6:17–18). In the governor’s absence, the high priest Eliashib had given Tobiah access to the temple storage area for his own household goods, removing its supplies of grain and frankincense. On his return to Jerusalem from reporting back to Artaxerxes, Nehemiah drove Tobiah from the temple area and restored the supplies and other temple objects (13:4–9).

This is one of several reforms Nehemiah mentions in completing his memoir. Laxity had crept into the management of the temple. Nehemiah discovered that financial support for the Levites had declined and that the singers had returned to farming. Correcting these failings, he called the leadership together, restored the giving of tithes and offerings, and set treasurers over the storehouses (verses 10–13).

Other reforms during his governorship included strict prohibition of work on the Sabbath, including harvesting, winemaking and trading in Jerusalem with local peoples. He also had to correct the practice of intermarriage with women from Ashdod, Ammon and Moab, reminding his fellow Jews—including the priesthood (one of Eliashib’s grandsons had married a daughter of Sanballat)—that Solomon had failed because such pagan wives had taken him away from God (verses 15–29).

In a typically humble conclusion, Nehemiah asks for the third time in this chapter that God look mercifully on him for his positive achievements and not for his own failings: “Remember me, O my God, for good!”

Next time we’ll take a look at the book of Job, the author, date and exact setting of which have stirred much discussion among Bible scholars. Many agree, however, that the book is a literary masterpiece. Certainly, its lessons are profound.