Charles Darwin and Natural Selection

Explaining How Evolution Might Work

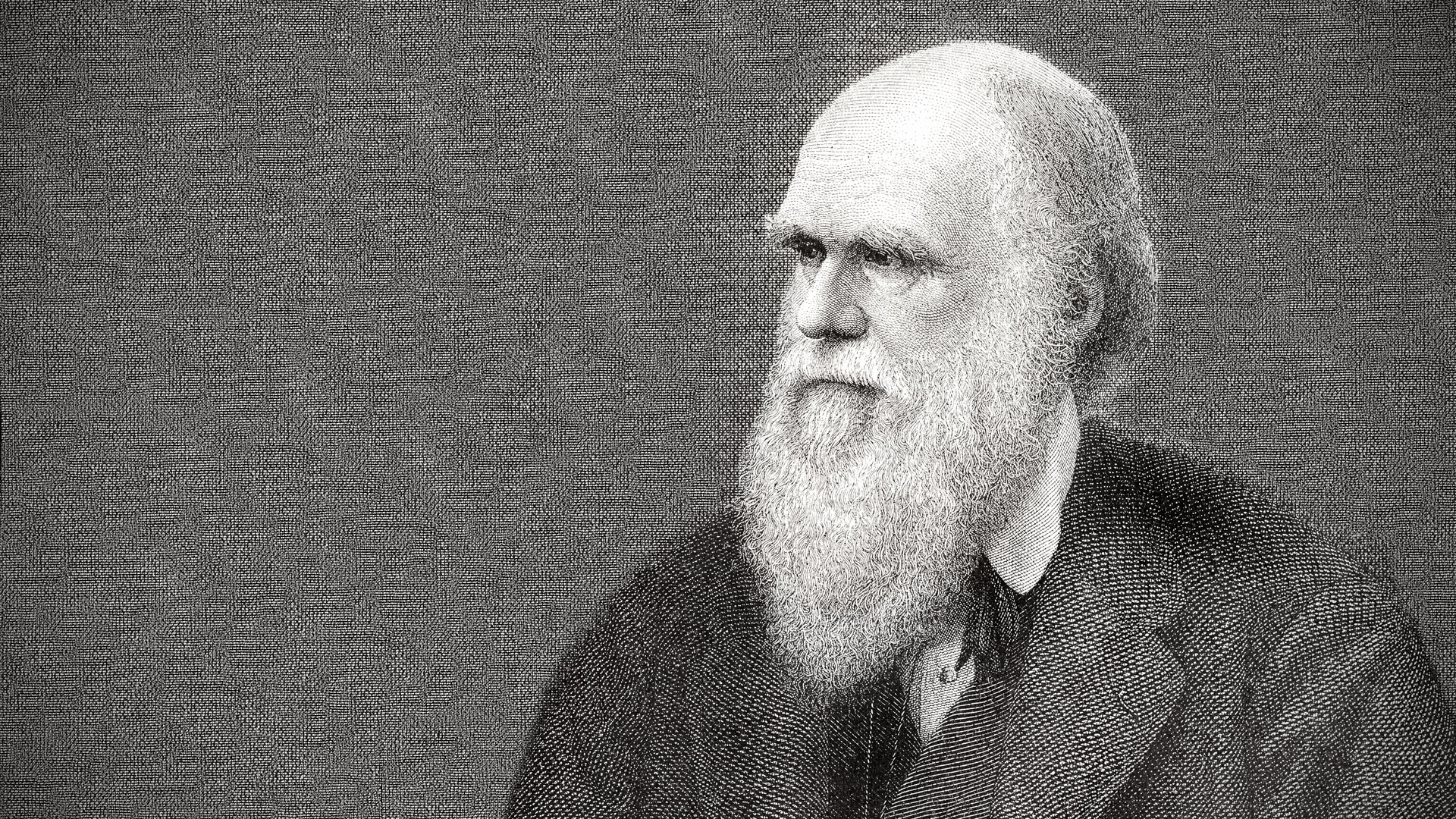

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire (England), in 1809 and died in Kent in 1882. Though his life began and ended in the 19th century, his ideas had a profound effect on life and thought in the West throughout the 20th century.

Born the very same day as Abraham Lincoln, 4,000 miles away in the New World, Darwin did not share the emancipator’s humble beginnings. He was born in a mansion, son of a well-to-do physician and grandson of two of the most famous (and rich) men of his time: scientist and poet Erasmus Darwin; and on his mother’s side, Josiah Wedgwood, well known even today for his distinctive porcelain.

As a young man Darwin studied medicine but realized that his squeamish disposition made it impractical to take it up as a career. He went back to university and studied to be a minister of the Church of England. He found, however, that he was more interested in his hobby—the study of nature.

Even while studying for the ministry, Darwin embarked on a field trip with Adam Sedgwick (one of the “big three” founders of modern geology) and earned encouragement for his clear skills as a naturalist. A year later, much to the chagrin of his father, he signed on as resident naturalist to HMS Beagle, a scientific exploratory ship, which was embarking on a five-year mission around the world.

During his service on the Beagle, Darwin decided to give up pretensions of becoming a minister and opted for the life of a scientist-naturalist. He made acute observations of birds, turtles and mammals, which gradually germinated into an idea that, though it had no new component to it, served to revolutionize almost every aspect of Western thought: the evolution of species by natural selection.

In the Galapagos Islands, 650 miles off the coast of Ecuador, Darwin identified 14 varieties of finches—not just breeds or tribes, but species (because they bred true, and bred only among their own kind). Each was distinctive from mainland finches, and this set Darwin to thinking.

Though religious, he was uncomfortable with the notion that God would have expressly created 14 varieties of finches to inhabit these islands, especially since they were all different from the few dominant varieties on the mainland. He reasoned that the birds’ isolation on the islands had itself brought about gradual changes that had resulted in the different varieties he observed.

Though religious, he was uncomfortable with the notion that God would have expressly created 14 varieties of finches to inhabit these islands.

In Darwin’s time, almost all naturalists already acknowledged evolution as a fact—defined as 1) gradual development, especially from a simple to a more complex form, and 2) a process by which species develop from earlier forms. There was great speculation, though, as to how evolution might work. J.-B. Lamarck (1744–1829) had insisted that animals acquired characteristic differences, which they passed on to their offspring.

In Lamarck’s scheme, the giraffe developed a long neck over many generations by stretching its neck. Though this view was popular in the scientific community of the time, Darwin dismissed it brusquely with the observation that Jews had circumcised boy infants for countless generations, but there were no signs of Jewish boys being born circumcised—yet!

Darwin came to believe that a simple process was involved. He reasoned that Galapagos finches sometimes hatched, by chance, with a little more curve to their beak. With the diet of different seeds available in their new habitat, Darwin concluded that descendants of mainland finches with the curved beak might find it a little easier to survive. Since that advantage meant that more curved-beaked finches survived to lay eggs for the next generation, there would be a little greater preponderance of curved beaks over time.

This seemed to Darwin a very satisfactory explanation of the great variety of different forms of finches found on the islands, compared to the one or two standard forms to be found at the mainland. He dubbed this gradual, gentle process natural selection.

Darwin was very slow to publish his revolutionary idea. In fact, it was after some decades that some of his friends urged him to publish his studies. Even then it was only after another naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) asked him to comment on his own forthcoming book, which to Darwin’s horror contained almost exactly his idea. Darwin finally rushed to print. (Wallace himself was eager to assure the public that Darwin had developed the idea of natural selection first, and more fully.)

With breakneck speed, more revolutionary thinkers pushed forward Darwin’s theory and extended its implications as an attack on religious notions. Thomas Huxley in Britain, Haeckel in Germany and Asa Gray in the United States battled not only Lamarck’s theory, but also religion itself. They insisted that evolution by natural selection did away with the need for creation—and the need for God Himself.

Today Darwin’s notions are almost totally abandoned by the scientific community, or at least heavily modified under the aegis of Neo-Darwinism. Natural selection is no longer viewed as sufficient explanation for the diversity of life. While Darwin was seeking to explain how one species could evolve into another similar species, some apologists extrapolated this to explain how whole classes of animals might somehow change into very different creatures (for example, reptiles becoming birds and mammals).

The extreme form of this thinking is that life itself first arose from nonliving matter by natural means—without any involvement by God. It is highly doubtful that Darwin himself ever thought natural selection to be an all-encompassing, God-replacing concept as all too many people have come to view it.

But the vast majority of naturalists today cling to the populist victory that Darwin’s supporters won—that science could now explain the creation without the need for a Creator. This effectively pitted the theory of evolution against religion in the Western mind and confirmed what many people wanted to believe: that the existence of God Himself was a theory that mankind could now do without.

Popular sentiment has failed to note that understanding how something works (survival) is very different from understanding how something came to be (arrival). As a result, evolution has been raised to doctrinal status from what it is in reality: scientific surmise.