Off the Assembly Line

Nurturing children’s unique qualities requires a different approach to education.

“Back to school” means different things to different people. New clothes, backpack and supplies. A new computer. Tuition deadlines. New beginnings. For some small children with enthusiastic and encouraging parents, the prospect of school might inspire bright and excited expressions.

Unfortunately some parents view school as little more than a free public babysitting service. And for many students, especially as the years roll by, it can become a return to a dreaded treadmill, something anticipated only for an enlivened social scene and seeing friends again. This transition from curious expectation to head-slapping, glassy-eyed boredom comes all too soon for many of our youth.

One might argue that this is the way it has always been—that the vacuous routine of school is part of the modern cycle of life, getting one ready for 9-to-5 careers. And summer vacation is just a proxy of our real goal: retirement.

If the purpose of school is to prepare children for adult lives of dull, bell-to-bell routine, then most reports would be cheering the success of the education system. Of course, that isn’t the case, nor would anyone accept that this is really our schools’ mission statement. But is it really so far-fetched?

“Again and again in interviews with especially gifted and inspired people, one is told spontaneously and with a special glow that one teacher can be credited with having kindled the flame of hidden talent. Against this stands the overwhelming evidence of vast neglect.”

Over the last century public school systems around the world have been designed and standardized with that basic concept in mind: to prepare a small group of people for managerial training and a larger cohort for the labor market. When stated so plainly, the gap between what we really desire from our schools—that they help guide our children toward their best talents—and the reality that stands before us, is huge. Without minimizing the real improvements that have been made in general education for an ever widening diversity of children, nor the many instances of individual accomplishment, we must acknowledge that we’re squandering a great pool of latent talent. This is creative potential that many critics of the system argue we will need in the challenging decades ahead.

Tragically, not only have we lost sight of this gap between what we hope for and what we have, but the gulf is widening. The achievement gap reaches far beyond the headlines of ethnic inequalities and annual international comparisons. Like industrial fishing, our current education system can surely claim the big catch—the trophy student who “exceeded all expectations.” But it is the wasted bycatch accompanying the successes that should draw our attention: the high percentage of students who either drop out of the system or are so ill-served that they walk away with sham diplomas that they cannot read. These and similar stories are certainly shocking and do receive headlines around graduation time. What is overlooked, however, is an even more disturbing story: the countless graduates who walk away with little sense of what to do next, what their talents are, or how to apply and contribute them to the world at large. They may have a diploma but have not learned what is most important: Who am I?

Decades ago Canadian mass-communications theorist Marshall McLuhan noted the growing gap between school traditions and students’ needs. He recognized that as the world changed, students would be the first to recognize the disconnect between present practice and the world they would inhabit. “Before we can start doing things the right way, we’ve got to recognize that we’ve been doing them the wrong way—which most pedagogs and administrators and even most parents still refuse to accept,” he told interviewer Eric Norden in 1969. “Today’s child is growing up absurd because he is suspended between two worlds and two value systems, neither of which inclines him to maturity because he belongs wholly to neither but exists in a hybrid limbo of constantly conflicting values.”

Can this gap be closed? How can we help our children, our students, our next generation of leaders navigate today’s education system? We may hope for change, as do many advocates for reform, but our children live in the system today; they cannot wait for a future thaw that may move the glacier. Parents are their child’s primary teacher. Reshaping what we expect of school, understanding some basic neuroscience, and taking a more enlightened stance in helping children understand their own experiences, accomplishments and failures, will go a long way in steering them toward successfully discovering their own path forward.

Society as Organism

A key concept that parents can teach their children is that no one in life is an independent contractor. Our lives extend to and touch many others each day. It’s a simple lesson that we sometimes mistakenly teach children to ignore. This connectedness reaches far beyond modern ideas of being wired to the world through our various electronic connections. We each rely on others “out there” to do their jobs so that we may do ours and enjoy all the conveniences of cosmopolitan life; however alone we may feel, our independence is an illusion.

When we see this big picture, it is clear that we should be helping our children become eager to take their part in the wide-open human enterprise, the more so because our trajectory from agri-industrial society to a knowledge-based and global economy has made all of our lives even more intertwined. We live in a symbiosis with all others: some farm so we may eat; some watch over the electricity and others over the water; some build, some bake. Like cells in a body, we are interconnected and interdependent; we must all work together in a holistic fashion if societal harmony is to be achieved.

The human body is an apt metaphor for the community at large: the idea that its parts fall into place through competition and friction is absurd. Our physical bodies do not grow through one part striving over another. Instead, from our embryological beginnings forward, we grow through the cooperation and communication of all our subparts, even down to the inner workings of every one of our 100 trillion cells. On that basis we should help children discover their place in the world. It serves us all if more people can reach the full potential that their individual talents afford.

“Our education system has mined our minds in the way that we strip-mined the earth for a particular commodity. And for the future, it won’t service. We have to rethink the fundamental principles on which we’re educating our children.”

This is not to imply that standards of expertise are unnecessary; children must learn the skills that enable them to participate within the body of society. Literacy and numeracy skills must be acquired, for they are foundational, but they need not be learned through teaching methods that emphasize competition. Developing a spirit of cooperation is a better lesson plan. As sociologist and educator Max Lerner argued in Values in Education (1976), our goal must not be to run some down so that others may be lifted up. “The aim of education . . . . is to bring all the resources of the cognitive, intuitive, and creative life of the society and the self to bear on shaping the mind, psyche, and person of every member of the society, so as to develop both the self and the society.”

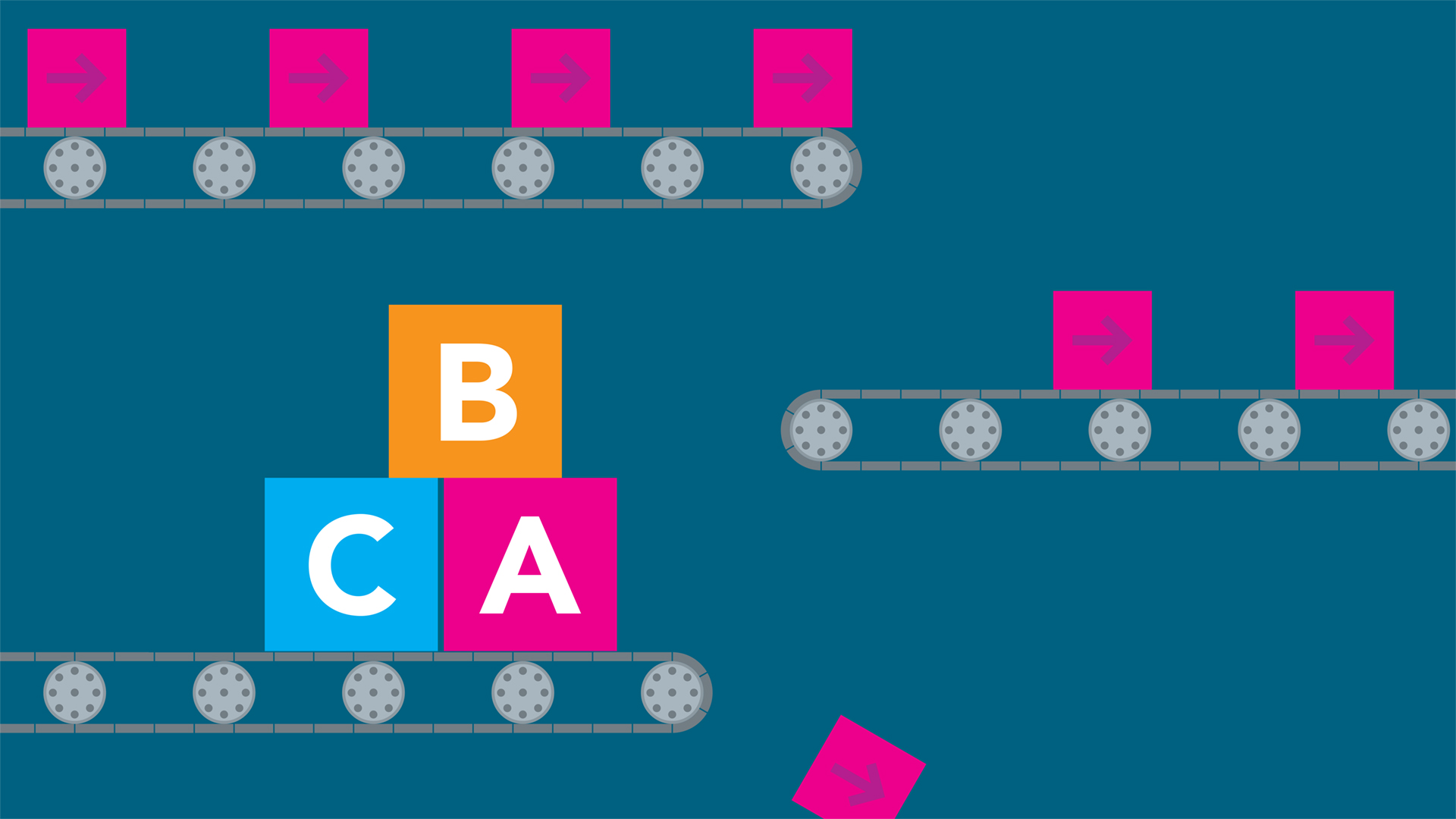

Continuing, Lerner notes the ecological, organic relationship that is at the core of the best learning environment: “All of education is organismic, and everyone involved in it is an organism.” This implies a mutualism where all may grow and gain together. The current system of education operates under a different paradigm, however—one of independent and discrete units: “The approach of educational thinking has tended to assume a mechano-morphic man—one structured around the metaphor of mechanism.” In this model the school becomes a kind of factory: teachers outfit students with the proper gadgetry per the syllabus; a bell rings; a new batch comes down the conveyor to be processed; repeat. A system that simply expects the student to march through, as if riding an assembly line, machinelike, serves the best interests of neither the student nor society. Lesson design that simply drills the mandated curriculum—the material that will be on the high-stakes test—in lockstep with the calendar is equally destructive. School should be a most personal place but has become one of the most depersonalized. Lerner concludes, “We must posit instead an organismic man, implying the metaphor of organism and environment and the vital relation between them.”

Investing in the Future

Children have always been viewed as capital—first the parents’ and then a nation’s most important investment in the future. Adults do many things to provide for and assure a viable future for children. Indeed, if this were not true, the whole structure of society would collapse.

In many Western and Westernized nations over the last century, business, capitalism and education have commingled to create the public school system. “Are our schools getting enough bang for the buck?” has been a preeminent question beginning in the early 1900s. The follow-on question, “Are our students prepared for work?” continues to be a driver of reform efforts.

In the United States, the impetus for the school-work connection was developed from the work of Frederick Taylor in 1911. “According to Taylor,” wrote education professor Raymond E. Callahan, “there was always one best method for doing any particular job and this best method could be determined only through scientific study.” Taylor’s theory of scientific management, combined with psychologist Edward Thorndike’s behaviorist theory of learning, helped establish a so-called school science. Through studies of cats and chickens, Thorndike had by the 1920s concluded that a stimulus-response-reward system enhanced learning. The continuing belief today that the correct stimuli (test scores, merit pay, etc.) will create better graduates can be traced to these ideas.

As Callahan argued, the goal of efficient use of public money and the tangential desire on the part of business for an obedient working class pushed school administrators away from being experts in children and education to becoming pseudo-experts in finance and public relations: “The great initial thrust for efficiency and economy against a young weak profession in the years after 1911 started the unfortunate developments in educational administration. . . . In retrospect, America might have been better off in the long run if American educators had taken a realistic look at what was expected of them and the means that were being provided and had closed the schools.”

Most of what we have experienced and accept as the status quo of modern schools in the United States and elsewhere—large class sizes in large buildings, a limited selection of courses, objective and easily scored multiple-choice tests, career or college-prep orientation, “stakeholders,” rows of seats, bell-to-bell instruction—can be traced back to the rules of efficiency and rote instruction outlined by Taylor and Thorndike. These structures embody what parents have learned to expect from school, because that is what they lived.

“What goes on inside the school is an interruption of education.”

However common this perception may be, clouded memory can trick us into believing that the status quo is best. So even if we choose to pay for private instruction, select where to place our education vouchers, seek out lotteries to gain entry to magnet or other specialized schools, or even decide to take the responsibility of homeschooling, we often try to emulate these conditions. Like a child playing teacher, we put the toys in rows and lecture to them.

While the imagery is true to form—school does look like this—its effectiveness has never been high. Even when it was efficient, turning out the sought-after 20 percent managers and 80 percent workers, many students simply left the system. Their refusal to follow the company line hurt the graduation rate numbers, but in the times when low-skill jobs were abundant there was little societal cost. Today we may fret over low graduation rates, but the upshot is that our schools remain poorly designed for the individual. This is what efficiency brings; the system is standardized. The tall poppies get cut down, if any grow at all.

School Choice

The negative long-term consequences of the assembly-line school are becoming more evident. Not only is such a system failing to meet the needs of society—as its critics have always insisted, whether from the business, moral, practical or cultural spheres—student discontent is growing toward critical mass as well. In all areas of life we are afforded choice. Whether in food, clothes, entertainment or electronics, everyone falls prey to the niche marketer. The suggestion to “have it your way” has become the clarion call of consumerism. It has penetrated every venue except the school.

In academic language, psychologist Kalina Christoff describes the inertia, “The standardization of examination methods and educational assessment is perhaps the biggest hurdle toward applying such an individualized and versatile approach to schooling.” Thus it is critical that parents engage with their child one-to-one if true individuation is to occur. Parents need not avoid the public school out of hand; they must understand its shortcomings and expect to compensate.

One purpose of the school has been to filter people down different paths. But the paths offered to the student have become increasingly constrained. Finances have contributed to this and so have the universities. Because they set certain entrance requirements and thereby bring greater legitimacy to some subjects and less to others, universities are to a great degree the driver of standardization. But while it is a myth that “you can be anything you want to be,” all children must be allowed to be something.

The problem remains, then, to enhance the futures of all children; once some go through the filters toward university, how can the rest be best served? Guideposts are necessary to delineate skills and direct students toward the development of skill sets beyond college prep. How much differentiation the school can or should provide continues to be a challenging question, but it will need an answer soon.

The growing danger is that fewer and fewer of our students are engaging in material they do not find personally relevant. They really do expect it “their way.” This is not simply a reconfiguring of the 1970s argument for introducing a wider selection of coursework from which students could choose according to their own tastes. The whole process of learning is better understood today, including the role of motivation; we realize that pushing all students down similar paths—down the same assembly line toward the same outcomes, even a good outcome such as college preparation—is truly irrelevant to many students.

McLuhan was prescient in this regard: “The challenge of the new era is simply the total creative process of growing up—and mere teaching and repetition of facts are as irrelevant to this process as a dowser to a nuclear power plant. To expect a ‘turned on’ child of the electric age to respond to the old education modes is rather like expecting an eagle to swim. It’s simply not within his environment, and therefore incomprehensible.”

We must become better stewards of both our students and our schools, especially in regard to students who do not exhibit the verbal and numerical strengths that present schooling is designed to draw on. “The coin of the realm in schooling is words and numbers, so much so as to constitute a form of educational inequity for students whose aptitudes are in realms other than verbal or mathematical,” says Elliott Eisner, emeritus professor of art and education at Stanford. Along with Howard Gardner, Eisner believes that student talents exist in a much broader range and suggests the obvious but difficult proposition that we “broaden both the curricular options and criteria that affect students’ lives.”

Support From Neuroscience

Clearly we are neither endowed with innate wisdom nor can knowledge simply be poured into us; we each must integrate our understanding of the world. This constructivist theory of learning has a long pedigree and modern support. “Instead of one brain area, learning involves actively constructing neural networks that functionally connect many brain areas,” writes neuroscientist and education psychologist Mary Helen Immordino-Yang. The researcher has done extensive studies of children who were able to overcome great deficits, even to the extent of missing brain hemispheres. These studies confirm the individuality of the construction process and lend further credibility to the theory of multiple intelligences: “Because of the constructive nature of this process, different learners’ networks may differ, in accordance with the person’s neuropsychological strengths and predispositions, and with the cultural, physical and social context in which the skills are built.”

Emotional development is also connected to academic success. “By turning teachers’ attention to emotional development, in addition to cognitive, it may be possible to modify educational practice to include a consideration of the social and emotional environments that children encounter during learning,” says psychologist Christoff. “This also suggests that it may be useful to consider possible expansions to the educational curriculum to include the acquisition of emotional skills that would enhance children’s emotional intelligence.” This, too, is something the savvy parent will incorporate into after-school discussions.

Neuroscience has illuminated the fact that we all have to some extent idiosyncratic mental pathways; this presents us with some hard evidence that all children cannot be expected to learn in the same way, no matter how well planned or educationally competent a particular teaching method may be. “Much too often, educational practice is solution oriented,” Christoff adds, “stressing the importance of reaching a solution much more so than the fact that there could be different ways of getting to it.”

Creativity as Capital

British educator Sir Ken Robinson focuses on the need for creativity, for allowing and encouraging students to explore these different ways. “The idea of going back to basics isn’t wrong in and of itself,” he remarks. “If we’re really going to go back to basics, we need to go all the way back. We need to rethink the basic nature of human ability and the basic purposes of education now.”

In a Technology, Education, Design (TED) lecture concerning education, Robinson notes that young children enter school with a blossoming desire to learn and explore. “If they don’t know, they’ll have a go,” he remarks during his presentation. Unfortunately, he argues, it is the push for the right answer through one-size-fits-all standardization of the schooling process that tears down the student’s intrinsic desire to learn and understand. Because creativity and originality require being wrong sometimes, Robinson points out that we need to be prepared to be wrong. But this runs counter to modern educational practice. The result, he says, is that “we are educating people out of their creative capacities.”

Helping students find “the meeting point between natural aptitude and personal passion” is what Robinson calls seeking “the element,” or their “most authentic selves.” Why is this important? Personal happiness is a good start, he says. How tragic it is to spend one’s life involved in a job that is a mismatch to one’s talents and aspirations, a job for which one has no passion. What if school actually helped me discover my talent? Beyond a sense of personal satisfaction and vitality, Robinson also notes the larger, organic benefit: people who are free to explore their native talents are more creative and are thus able to contribute more to society at large. In a changing and more crisis-prone future, he argues that we will need this creative spark. To truly invest in a student’s native potential would pay great dividends.

In his 2001 book Out of Our Minds, Robinson writes that “the dominant ideologies of education are now defeating their most urgent purpose: to develop people who can cope with and contribute to the breathless rate of change in the 21st century—people who are flexible, creative and have found their talents.”

The adult who should be most aware of the child’s strengths, weaknesses and talents is the parent. Teachers and other adults certainly want to help, but strong pressures often stymie their efforts. Parents must take a more active role in helping their children explore and cultivate their unique talents.

The real bottom line is that no institution can replace the responsibility we alone have for finding our right path in life. We pick and choose, through our interactions and experiences, who we will be. As one set of researchers found, it is not IQ that matters; the key factor is self-discipline. Our willingness to defer action and sometimes refuse the immediate to achieve a later goal is the skill that makes the real difference in what we will become.

Brain research has revealed that we are very plastic; learning and change continue throughout our lives. Identity is created, and it, too, is subject to new inputs, new learning and new conclusions. Old memories and habits that entrap us can be discarded at both the societal and individual levels. Likewise, we are collectively and individually responsible for seeing ourselves clearly and taking appropriate steps to change what we find out of place. The gaps we find need diligent, self-disciplined repair, not a temporary patching over. For both parent and child, and indeed for all of us no matter what our family circumstances, this is our most important creative enterprise.

On a personal level, this re-creation occurs from the inside out. Back to school? No, school is always in. We must examine first our inner selves, our mental voice, demeanor and attitude, because it is these that give rise to our outer behavior and being. Only as we change within will our created institutions follow.