What Dictators Have in Common

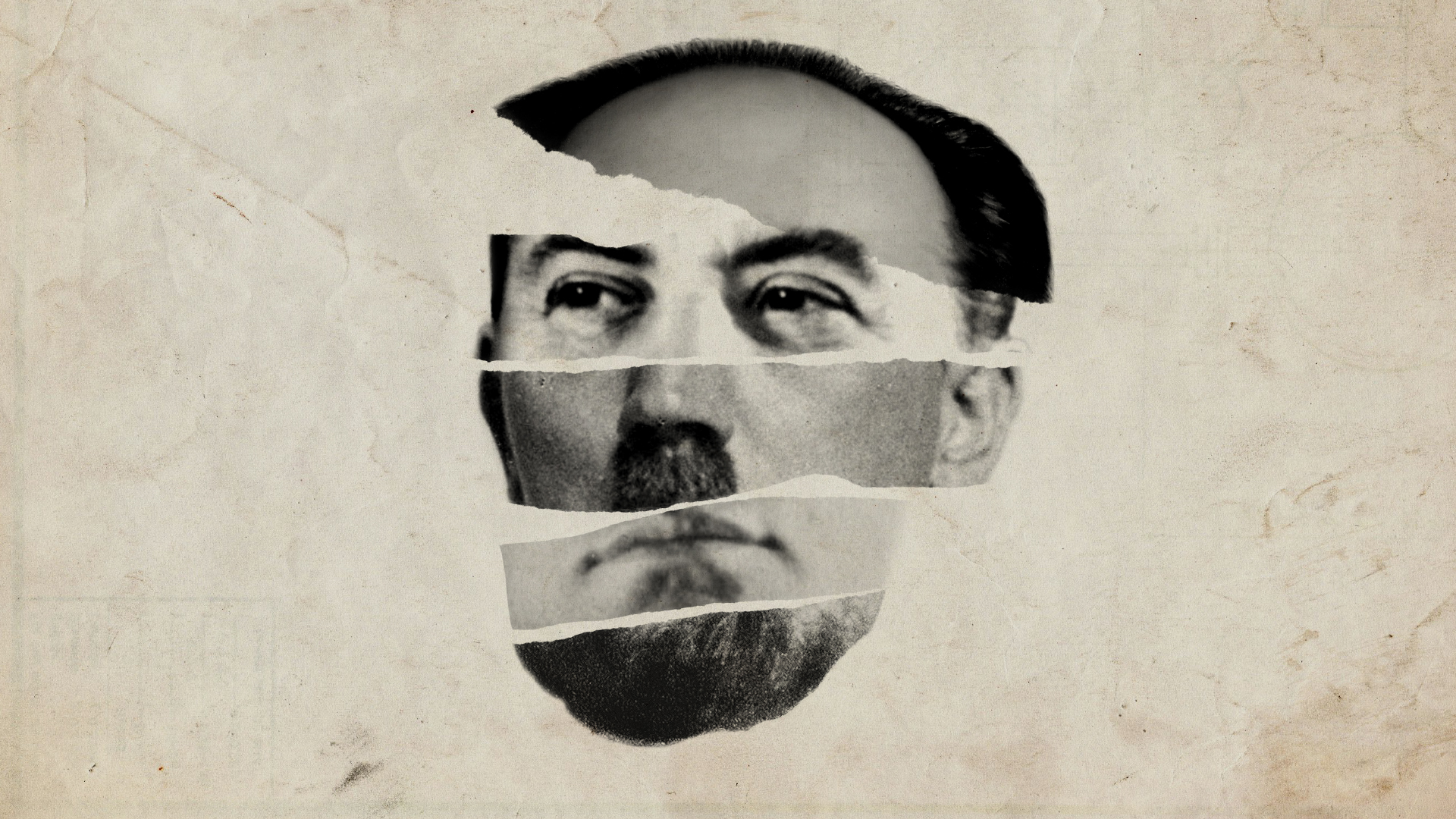

Totalitarians, autocrats, dictators—call them what you will; they’re on the rise. In country after country, the trend is toward strongmen and even military-style government. According to a recent analysis based on the World Values Survey, this shift is happening in many democracies, but the millennial generation (22–37 years old) in particular is expressing misgivings about liberal democracy’s effectiveness. It’s now possible to imagine the return of the worst features of dictatorial rule in the 20th century. Men such as Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler and Mao could reappear in different garb. The saying “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes” could have a terrible resonance a century later.

Those five totalitarians had at least five characteristics in common. It’s worth thinking about these factors, because autocrats are here now, and others are waiting in the wings.

1. Extreme Violence

Capacity for violence was a key trait of last century’s dictators. They were killers from the start. Before they ever gained power, they led terror groups against their own people, purged their followers, and displayed deep-seated hatred for various classes and ethnic minorities.

It was Lenin’s dictum that terror legitimized the state. Stalin mastered the concept as he rid the Soviet Union of “enemies of the state,” including politburo members, quotas of the innocent, and the entire class of farmers. Terror does not need a reason. Six to nine million lost their lives in Stalin’s purges.

Mussolini organized Italy’s post–World War I fascist terror group, the Fasci di combattimento. Once in charge of the country he purged close comrades and even his own son-in-law. He rounded up Jews and sent thousands of them to their deaths in Nazi camps in Austria. Hitler’s bitter manifesto, Mein Kampf, had laid bare his long-term goal of “cleansing” Germany (and the world) of Jews, Marxists, Slavs and any group he considered non-Aryan and/or inferior. Eleven to twelve million died under his hand, more than half of them Jews.

Mao Zedong followed a similar pattern. In the early days, he led the Long March of 80,000 communists for thousands of miles. Despite the epic journey they shared, Mao murdered colleagues and followers as together they terrorized the countryside. Only a fraction of the marchers survived to tell the tale. Once he attained power in 1949, his murderous ways became devastating on a greater scale. By the time his 27-year rule of China ended, an estimated 42.5 million had perished in waves of terror and purges, from starvation, and from brutal overwork.

2. The Cult of Personality

The personality cult, centered on the leader, is another aspect common to the dictators. In the Soviet Union, Lenin and Stalin were presented like saints in Russian iconic art, even Christlike, complete with halo. Italian schoolchildren were taught to revere Mussolini. After each day’s recitation of the Roman Catholic creed, they were to repeat their “I believe in Mussolini”; he could do no wrong and never be questioned. He allowed the myth that he was God’s gift to Italy.

Hitler, too, was viewed as a divine blessing, the Savior-Leader the German nation awaited. Followers lauded his mystical insight, compared him to Christ, and were overcome by a kind of religious conversion. Mao was the “Great Helmsman,” guiding his people to world power. Just reading The Little Red Book of the chairman’s thought was said to cure illness.

3. Adopting Religion for Selfish Ends

Closely connected is the co-opting of religion for political purposes. Though the Soviet federation was atheistic, Stalin knew that religion was a powerful means of uniting people. After Lenin’s death, he promoted the former leader as a messiah, embalming his body and placing it on permanent display as a kind of holy relic. Stalin would later adopt the posture of savior himself. During the height of his rule, a painting appeared showing the leader as Jesus at the Last Supper. Over his shoulder is an image of John the Baptist looking like Lenin.

One of Mussolini’s first acts as Duce was to have a crucifix placed in every classroom. But then he also wrote, “Fascism is a religious conception of life . . . , which transcends any individual and raises him to the status of an initiated member of a spiritual society.” Hitler initially forged a concordat with the Roman Catholic Church. He adopted Christian terminology in his speeches, creating the impression of a Christlike figure, a man of destiny. In reality he despised Christianity as a weak belief system. Mercy and forgiveness had no part in his war religion.

Mao Zedong much admired China’s Hong Xiuquan, a 19th-century Christian and self-proclaimed “Heavenly King.” Mao had a favorable impression of Hong’s messianic regime and took it as an inspiration, using it to legitimate his own. Yet Hong brought about the death of 20 million in his efforts to establish his kingdom.

4. Grandiose Self-Image

Delusions of grandeur were never far from the surface in these men’s minds. The conviction of being God’s chosen instrument, a superman, even the reincarnation of a previous strongman dominated their thinking. Stalin framed himself as vozd—the Leader and Teacher of his people. Mussolini saw himself as a new Augustus Caesar, ushering in a neo-Roman civilization. Hitler believed he was the Great Leader who would return Germany to the pinnacle of power after the humiliating defeat of World War I. Mao is said to have referred to himself as a god and a law unto himself.

“During the Cultural Revolution, . . . myriad portrayals of Mao showed the Chairman’s image inserted directly into the center of the sun, a phenomenon that clearly emerged as a response to the campaign to deify Mao.”

5. Eye on World Domination

Marxist-Leninism imagined the eventual triumph of communism as the new world order. Stalin promoted the same goal. Mussolini was intent on creating a new city within Rome, named EUR, as a model for the rest of the world, populated by the new man and woman devoted to fascist ideals. Hitler’s office in Berlin was so large as to give the impression that he was Master of the World. His new city, Germania, was designed to become the new world capital, and his Third Reich would last 1,000 years.

Mao’s appetite for power was all-encompassing. The role of supreme leader of China was insufficient; he wanted to take over the planet. He said, “In my opinion, the world needs to be unified. . . . In the past, many, including the Mongols, the Romans in the West, Alexander the Great, Napoleon, and the British Empire, wanted to unify the world. Today, both the United States and the Soviet Union want to unify the world. Hitler wanted to unify the world. . . . But they all failed. It seems to me that the possibility to unify the world has not disappeared. . . . In my view, the world can be unified.” It’s said that he created an all-earth committee to oversee global transition to Chinese rule.

These five characteristics of totalitarians are remarkably evident in what biblical forecasting says about a final autocrat referred to as “the beast.” As the world’s ultimate dictator, he is predicted to rule with the ferocity of a wild animal in the tradition of the Roman Empire of old. That system is described as a voracious and violent beast with “huge iron teeth” (see Revelation 13:1–4; Daniel 7:7). Other leaders, we’re told, will voluntarily submit to his leadership for a short period, and all tribes, tongues and nations will fall under his authority (Revelation 17:12–13; 13:7). His ally, a great religious leader, will make use of miracles and convince people to worship this “beast” (Revelation 13:11–15). Like others before him, that last dictator will claim divinity, sitting like God in His temple (2 Thessalonians 2:4). And he will head an economic and political combine with global reach (Revelation 18:11–13).

Can it happen? Given today’s trend toward autocratic leaders, there’s no reason to think it can’t. But in a take on the famous comment often attributed to Mark Twain, modern historian Timothy Snyder says, “History does not repeat, but it does instruct.”

Seeing before us the dangers of tyranny, let’s hope we accept that instruction. When such a final dictator comes, you and I don’t need to be unaware of his arrival nor join in his fate.