The New Anti-Eugenics

Making Sense of Our Genetic Differences

Kathryn Paige Harden, author of The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality, discusses the role of genes in determining why some of us achieve greater success in life than others.

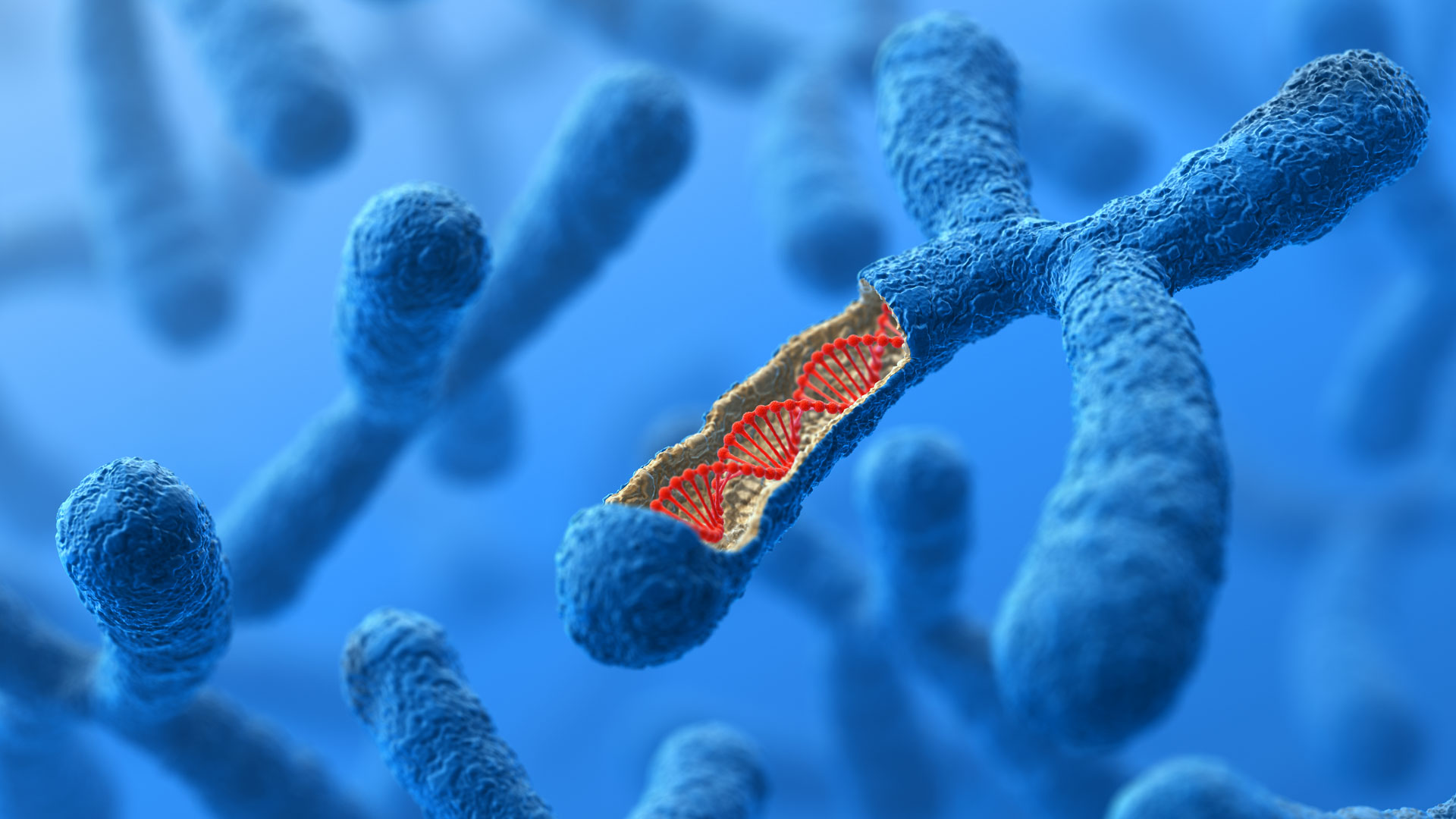

This year marks 25 years since the release of the 1997 science-fiction classic Gattaca (the title’s G, A, T and C representing the subunits of DNA). Several dystopian genetic themes converge in the movie, including genetic identity and human value.

The film is set in a future where newborns are genetically profiled and then tracked into “valid” or “in-valid” life paths—a most disconcerting scenario, not because it’s a grotesque fiction but because, in some respects, it’s actually not far from where we are today. In the current debate about genetics, there are those who use the “objectivity” of chemical code to establish a hierarchy of human worth. In the eugenicists’ view, genetics largely determines a person’s life course; some are born to advance and succeed, while others are born to be subservient and to perform menial jobs. On the other side of the debate are those who argue that because we’re all 99.9 percent the same genetically, genetics has no place in a discussion about unequal life outcomes and must be abandoned.

Neither view is correct, says Kathryn Paige Harden.

“Proposals to select people for desirable educational and occupational positions based on their measured DNA are flawed on both empirical and moral grounds,” she writes in her meticulous first book, The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality.

But to suggest that genetic differences should play no role in how people are treated—that everyone should be treated exactly the same—is just as wrongheaded: “The long causal chain connecting the genetic lottery with social inequality means that decisions about equity—about what we want the world to look like—must be made at every link in the chain.” Harden contends that “genetics, far from being an enemy to, or a distraction from, the effort to improve human lives, is in fact an essential ally, one that is abandoned only at great cost.”

Harden, a psychologist and behavioral geneticist at University of Texas–Austin since 2009, is codirector of the Texas Twin Project. Her lab’s work concerns early adolescent development as well as the interplay between genetic variation and experience, which leads to divergent life paths and outcomes.

“Knowing what we know now,” Harden writes, “we cannot pretend that genetics do not matter. Instead, we must scrape away the eugenicists’ scientific and ideological errors, and we must articulate how the science of heredity can be understood in an egalitarian framework.”

Harden calls that framework anti-eugenics. “The anti-eugenic policy,” she says, “is one that guarantees equality of freedoms, resources, and welfare regardless of the outcome of the genetic lottery.” It asks, “Can we make social structures that are good for everyone, regardless of the hand that nature dealt them?”

Vision’s Dan Cloer spoke with Harden about anti-eugenics and how to make the next 25 years better.

DC We’re all the product of the gene lottery; each of us receives a randomized and unique combination of our parents’ genes. You use NBA basketball player Shawn Bradley as an example of someone extremely tall from parents of normal height. What is the relationship here between social outcomes and genetics?

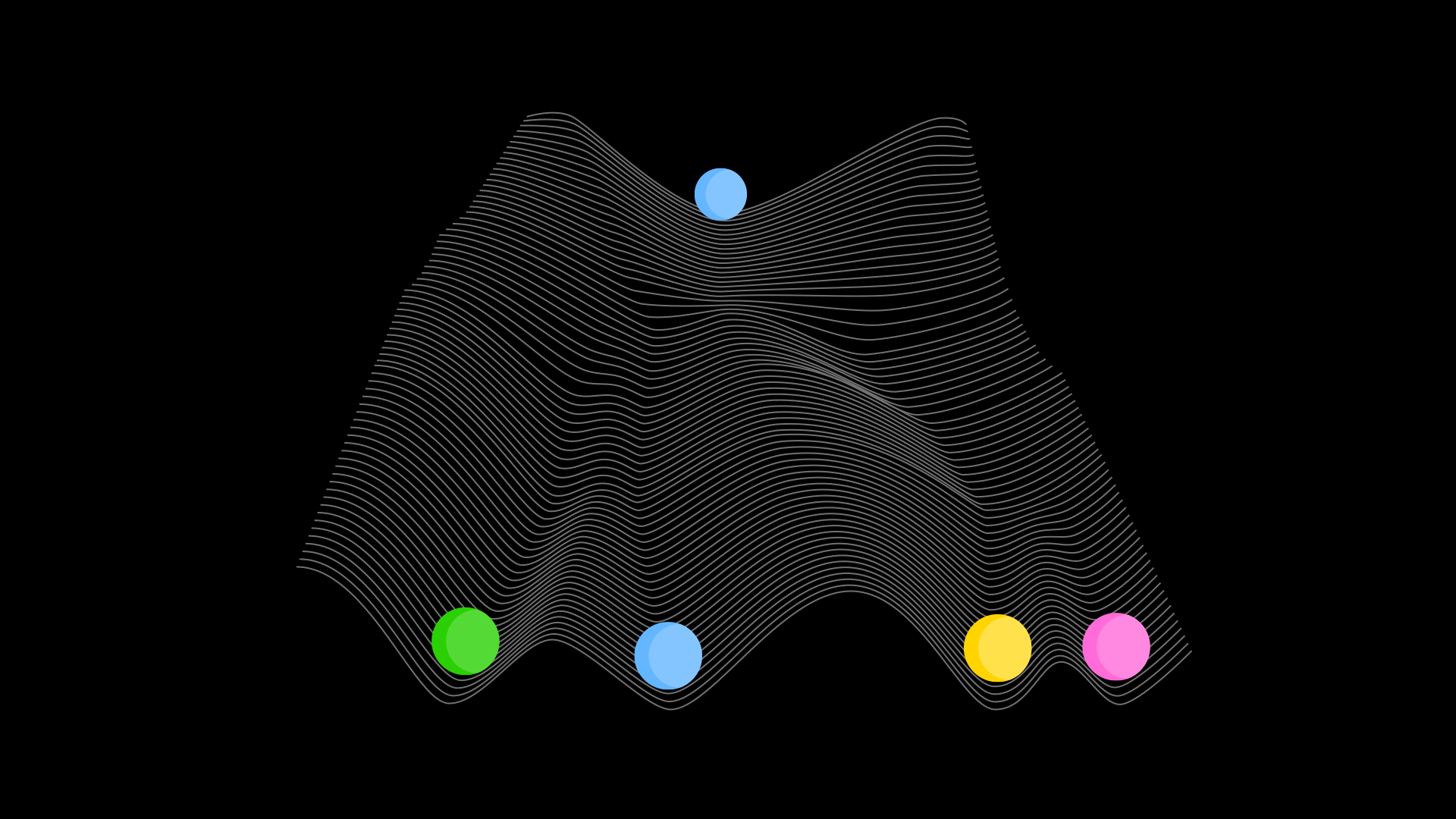

KPH Well, let’s start by thinking about the genetic lottery. Your parents have two copies of every gene, and you only inherited one. So, every gene is like the flip of a coin, and your genome is millions of flips. You may get heads 10 times in a row, or tails, or any combination. Your genome, then, is a new, one-time result (unless you’re an identical twin, and even there are opportunities for differences). Height is not influenced by just one gene but by a combination of many.

But what’s really interesting is that there are actually two lotteries. The first is the genetic lottery that I just talked about; for Shawn Bradley to end up where he is—which is a bazillion standard deviations to the right, physically—you had to flip that coin and it had to end up heads, like, 50 times in a row. He beat the odds and was very, very tall. But in addition to Bradley’s genetic luck, there’s also the luck of being born in a particular place and time where people play professional basketball. Imagine if Shawn Bradley were born in France in 1740. Maybe he’s slightly better at working the machinery on his farm, or he’s very good at felling trees. Maybe not. But his height isn’t economically valuable in the same way. Not only do you have a genetic lottery, you also have a social structure in which that individual difference is refracted.

“There’s the luck of having a certain set of genetic variants, but there’s also the luck of living in a particular point in history, such that you were rewarded for that set of traits.”

So it’s your genetic makeup, as well as how that makeup was translated into human capital development, given the social inputs of your childhood; and then, how is that human capital rewarded or not rewarded, given the structure you live in. It’s all three of those, always. It’s never just the genes.

DC And it’s not just height or abstract thinking.

KPH Right. Nearly every psychological and physical difference between people is influenced by many, many genes.

DC In your book you explain your hope that by understanding our genetics, we might develop ways to make society more equal. As a researcher, how do you keep your science from just confirming what you want and expect to find?

KPH Oh, that’s such a good question. The core of the scientific mindset is the search for disconfirming evidence. In setting up your scholarly practice, your lab, your experiments, your research studies, you must have strong tests where you have a real possibility of finding something that disconfirms your hypothesis.

“If there’s no way to ever reject incorrect hypotheses, then you have pseudoscience.”

Scientists are people. We all have our confirmation biases; that’s part of being human. But part of scientific praxis, in terms of being in community with other scientists and the rules of scientific communication, is always being around people who like you and tell you that you’re wrong all the time! That’s the fundamental, weird experience of having other scientists as friends and colleagues. It doesn’t matter how much someone likes you or how warmly they feel toward you as a person; they will still—in public and in private—tell you all the reasons why they think your interpretation of the data is wrong. It’s a habit of thought that’s not only trained but also deeply social. Humans are bad at looking for disconfirming evidence in isolation.

DC You’re proposing what you call a “new synthesis” that establishes a connection between genetics and human outcomes, but without the eugenic baggage of hereditary superiority. What balance are you trying to strike?

KPH The eugenic thesis is that there are genetic differences between people. They matter for their lives; they’re immutable, inexorable, and they can’t be “fixed” with social policy. This makes society a kind of natural aristocracy, where inequality is rooted in biology and is therefore inevitable and just. This means the only way to change things is by interfering with people’s reproduction.

The antithesis to that idea has long emphasized genetic sameness and environmental malleability. It insists on the irrelevance of genetics for inequalities and life outcomes.

The peaks of those two ideas were really Hitler (there is a master race and the only solution to biological inferiority is genocide) and Stalin (genetics is the enemy of class progress and of egalitarianism).

Those two ideas—in more diluted, subtle form—really dominated most of the conversation about genetics in the United States post–World War II. Some would say, “We can’t boost IQ. We can’t boost scholastic achievement. There’s a racial hierarchy, a class hierarchy. It’s genetic, inevitable and just.” And another group opposes the idea of linking genetics with difference at all. So when I say synthesis, I mean I want to reject both the thesis and the antithesis. I want to think about egalitarianism as a social, moral, political project. How does it coexist with a recognition of genetic difference between people?

DC Is that synthesis what you call anti-eugenics?

KPH When I was writing I hadn’t seen that word used before, but other writers since then have also used it, so I think people are coming to the same idea from different places. I’m using the term to parallel the vocabulary of “anti-racism” as opposed to “color blindness.” If you say, “I’m going to treat everyone exactly the same regardless of race; I don’t see race,” this can actually perpetuate a racial hierarchy under misguided neutrality by feigning being blind to race.

What I’m trying to do is contrast genome blindness—“Let’s just never peek under the hood and study how genetics is related to differences,” which allows, I think, genetically related differences to continue to structure society under that guise of neutrality—with anti-eugenics.

“In place of a faux neutrality, we can say: ‘I see difference; I see how genetic advantages and disadvantages play out. How do I use that information to level social hierarchies rather than naturalize them?’”

DC In your book you make several references to your children and their unique differences in the context of equality and schooling. How does this connect to the idea of leveling the hierarchies?

KPH I was writing about the idea of accommodating differences, but first you have to see them. In a school context, consider Individualized Educational Plans, which are clearly about recognizing differences. What we’re trying to equalize in school is not necessarily children’s psychological functionings but their ability to profit from instruction in this school.

So much of the discussion around equality in America is really stuck in this “equality of opportunity” rhetoric, which can be narrowly interpreted as exact sameness: we treat everyone exactly the same under the law. But that’s not enough. Any educator knows that if you did the exact same thing for every kid in your classroom, you’re not providing equality of opportunity for them to profit from instruction. At the same time, any educator knows they cannot guarantee equality of outcome. We know that even if everyone in the entire world had the most perfect education for them, there are still going to be differences. Because humans are infinitely variable, outcomes vary.

Think about the Americans With Disabilities Act. It specifies equal enjoyment of and ability to access a place of public accommodation. We cut curbs, and that recognizes and accommodates differences between people. In fact, curb cuts help everyone, not just those who were the original object of that policy. It makes easier the lives of women pushing strollers, bicyclists, kids with scooters, lots of people. So the thought process is: I see difference in functioning; I see how difference in functioning matters in our structures. How can I change our structures to recognize and accommodate that difference, and in so doing make everyone’s life better?

The anti-eugenic synthesis, then, is about how we see and respond to difference. Difference is not a justification of the existing social order, and not something that needs to be ignored, but something that, by seeing it, we are better able to bring about a more radically equal enjoyment of our collective society and the goods that flow from that.

DC Where does your egalitarian ideology come from? You write of your religious upbringing. That seems to underlie your sense of social justice, which seems to be further informed by your science.

KPH The eugenic idea is fundamentally about human inferiority and superiority, and I think in the New Testament that hierarchy is removed. We see statements that there’s neither male nor female; there’s neither Jew nor Greek. Think about what that meant in the sociopolitical context of first-century Judea: it’s a radically egalitarian statement. To talk to Samaritans; to talk about Samaritans being good: this is a breaking down of the social orders of a key system that existed at the time.

Also, is there anything that Jesus talked about more than wealth and our obligations to the poor?

“How do we think of the poor—that the meek will inherit the earth, that whatever you did unto the least of these, you did unto me? Those are radically egalitarian ideas.”

I should say that I don’t necessarily believe in a historical Jesus who literally said those things. But I think if we take the Bible seriously, even just as literature, we can explore “What does this book have to teach us? What does the main character talk about?” That has stayed with me, even as my belief in a God has wavered over the course of my life.

DC From your investigations of the connection between genetic differences and social outcomes, many people would expect the answers to be race-based, but you’re saying they’re not. How can we understand race as you do, as a geneticist?

KPH When we look around, we see physical differences between people, and they’re related to parentage and to geography. So to say that race isn’t biological strikes people as profoundly counterintuitive and counter to what they observe about the world. There are a couple things to remember here. First is that clearly people differ in genetic ancestry, which is a function of who had sex with whom, going back multiple generations in your family. People have sex with people who are next to them, right? So it’s geographically structured. But this geographical variation is much more fine-grained than our social categories of race.

Think about someone like Barack Obama, who has a white mother and an African father and is socially categorized as Black. Already we see a complex genetic ancestry—a European-ancestry mother and an African father. But even within people of African ancestry, we see genetic differences across the continent. People of African ancestry can be as genetically different from one another as Northern Europeans are from the Han Chinese—an enormous amount of genetic difference that is just flattened and smooshed together in the US under this category of “Black.” The same thing with Asians. In the United States, we put Southeast Asians, Indians and East Asians in one “Asian” category on the census. That is just wild, from a genetic perspective—as if we decided to take everyone from Europe to Africa and just arbitrarily said they’re all the same race. It doesn’t make sense, genetically or culturally. Why, then, do we have these either/or—“you’re either Black or you’re not”—social categorizations that are such bad proxies for genetic inheritance?

To understand that, we need to ask at what point we started to use the word race, even to describe these social groupings between people. At what point did race become a word for geographically disparate groups of people? It’s with the advent and rise of the global slave trade, in particular in America and England. It’s hard to write about democracy and equality and also have a massive slave trade. The inherently hierarchical concept of race justified their coexistence. We became invested in the idea of racist biology. From the beginning the idea of “race” was invented as a tool to justify slavery and racial oppression, not because it was a good proxy for what was going on under the skin.

When I say that race is not biological, it’s because it doesn’t reflect the biological differences we see between people genetically, and also because it wasn’t a biological discovery. No one said, “I’ve mapped out the biological differences between humanity, and now I’ve come up with this concept of race.” It was the opposite: “How do we have a moral apology for slavery in countries where we’re advocating for greater democracy?”

“Biology and race are smooshed together in the public imagination for a reason. That idea was deliberately propagated for decades, if not hundreds of years. Trying to find biological differences between these races comes after the fact.”

DC You use Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) to look for genes associated with particular outcomes—but not for racial correlations and predictive conclusions?

KPH Right, it doesn’t really apply in that way. A GWAS study produces a polygenic score measuring genetic differences. But you’re trying to compare apples with apples, in terms of genetic ancestry, not compare people across broad population differences. That means you end up with genetic associations that are not very portable and are only relevant to understanding individual differences within a population.

The standard practice is to restrict your study to people who are as ancestrally homogenous as possible; for instance, people who describe themselves as white British on a survey, and who, when you look at their genomes, all have recent genetic ancestors who came from the same part of the world. You’re trying to avoid what people call the “chopsticks gene” problem: Let’s say you had a big group of white British people and Chinese people mixed in a GWAS. Could you correlate which genes were associated with the use of chopsticks? Well, any genes that were more common in Chinese people versus British people would be correlated with using chopsticks. But that’s not because anything about that gene is causing differences in manual dexterity. It’s just that people who are geographically different are culturally different, but also genetically different. So, you’re not actually identifying something real about their biology (genes) in its relationship to this outcome (using chopsticks).

The best solution is to do your GWAS in a sample of family members—always comparing siblings to siblings. Currently, although I think this is going to change, there aren’t enough samples of siblings to make that a feasible strategy. So, the intermediate solution is to look for people who are not family members but who are, in some ways, distant family members by virtue of sharing genetic ancestry—having the same genetic background.

DC And race doesn’t fit this criterion?

KPH That’s right, because 1) race is a really bad proxy for ancestry; and 2) the polygenic score is designed to look at differences within an ancestrally homogenous group. To take a polygenic score developed from a genetic study of European-ancestry people and then ask, “How different are black school children on this?” would be scientifically nonsensical. It’s profoundly unintuitive for people, because the idea of genes and race and IQ are so smooshed together in the public imagination, whereas scientifically they’re orthogonal [statistically independent] dimensions of inequality. We can see racialized differences in equality in America; and then within racial groups, there are ancestral differences, and within ancestry, there are individual genetic differences. But right now, the genetic information isn’t informing us about the racialized differences at all. It’s mostly just telling us about what’s going on with white people in the United States, because we just don’t have the data on other differences.

DC And that’s because most GWAS work has been done using populations of white people. So the correlations you’re finding between educational attainment, social outcomes and stratification are part of the genetic lottery?

KPH Race is obviously a vital part of the social inequality picture in America, but it’s not the whole story. I find it so interesting that people really underestimate the degree of social inequality among those who identify as white in the United States; most people on public assistance or some sort of welfare here are white.

“If we think about the divergences in mortality and wages, in marriage rates, in college-educated and non-college-educated, whites represent some of the largest differences we see in the American landscape.”

We see, increasingly, non-college-educated whites falling further and further behind in terms of marriage, wages, lifespan, psychological well-being.

DC The idea of the lottery really speaks to the reality we’re in, and we should all probably think about it more. Still, many believe we all get what we deserve, or earn. Anti-eugenics gives a more rounded picture of how to consider each other.

KPH This idea of “getting what you deserve” came up for me recently when there was still the possibility of some student loan forgiveness [by the US government], and there was this whole Twitter conversation about which people deserve to have their loans forgiven, or have earned it; and I just thought (this is the other thing that stuck with me from my Christian upbringing): Give people more than what they deserve!

Who are “the least of these” in our society? If you really took it from that perspective, we might think more about what we owe the high school dropout, the teenage mom, the person who has struggled to hold a job. What do we owe these people by virtue of their being human?

Think about how the Gospels ask you to consider your neighbor, to treat your neighbor as yourself. In a way, it’s an idea that wouldn’t be out of place in the work of the philosopher John Rawls: What if you had your neighbor’s life? What type of society would you want then? If you were behind the veil of ignorance and you had no idea what you were going to get in the genetic lottery, or the social lottery, what kind of society would you want? You’d want a society where, even if you got the short end of the stick, socially and biologically, you would still have the ingredients of a good, fulfilling life.