The Coming of the “Christian” Emperor

In Part Two we examine the life of Roman emperor Constantine the Great. Again we see the surprisingly deep roots that some notions of rulership, and their connection with religion, have.

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 1)

GO TO SERIES

During daylight hours of October 27, 312 C.E., Constantine and his 98,000-man army are said to have seen “a cross-shaped trophy formed from light, and a text attached to it which said, ‘By this conquer’” (see Eusebius, Life of Constantine 1.28). At the end of his life in 337, the emperor told the historian and bishop Eusebius that the next night Christ appeared to him and ordered him to put the sign of the cross on his battle standards. Having done so, he went on to defeat his brother-in-law and coemperor, Maxentius, on October 28 at the battle of the Milvian Bridge, then two miles north of Rome. Constantine seems also to have told this version of the story on Good Friday 325, in a speech now accepted by scholars as authentic, as he explained that he saw himself in history as God’s servant.

Though Constantine had really won the victory a few days earlier in the Po Valley on his way to Rome, his success at the Milvian Bridge has been regarded as a turning point in world history. Soon he was the sole emperor in the West and several years later was able to unite both Western and Eastern parts of the empire and establish a “new Rome” at Constantinople.

More significant in its effect to this day, however, was the favor he bestowed on Christianity, or more accurately the Roman version of the faith. Barely three months after his victory outside Rome, Constantine, along with his coemperor in the East, Licinius, initiated a new religious policy for the Eastern empire. The official statement was issued a few months later by Licinius and is often wrongly referred to as the Edict of Milan. The document, which went out from Nicomedia in western Asia Minor, extended the rights and privileges of Christians in the West (which had been reestablished in stages throughout Constantine’s early years of rulership) to those in the Eastern empire. There would be no more persecution of Christianity, and confiscated properties would be returned to Christian owners.

When Constantine was born, probably around 272 or 273, Roman Christianity was already becoming an accepted religion. In 260 the emperor Gallienus had reversed his father Valerian’s persecutions and declared Christianity a legitimate religion (religio licita). Within 40 years there were Roman Christians in the palace, in the army, and in imperial and provincial administration. Nevertheless, in 303 Emperor Diocletian ordered renewed persecution of Christians.

Constantine’s own father, Constantius, was a coemperor in the West at the time. Though not a Christian, he was sympathetic to monotheism—the idea that one supreme god ruled all religious cults. With this background, it is therefore not difficult to understand why Constantine became the defender of the empire’s increasingly popular religion when he came to power in 306. According to Robert M. Grant, “by 312 he had realized how helpful the Christian church could be, and with the aid of a secretary for church affairs he began to intervene in such matters so that he could promote the unity of the church” (“Religion and Politics at the Council of Nicaea,” in The Journal of Religion, Volume 55, 1975). That secretary was Hosius, or Ossius, bishop of Cordoba in Spain, who became ecclesiastical advisor to Constantine and seems to have had a strong influence on him.

Conflicting Visions

Despite the importance that Constantine’s heavenly vision has assumed, the story has been muddled by seemingly contradictory evidence. Eusebius’s account, quoted above, is from a work usually dated 339. It differs in important details from the earlier account in his Ecclesiastical History (9.9.2–11), dated 325—when he first met Constantine—in which there is no mention of a vision or a cross or the appearing of Christ. Certainly there is no record of any of Constantine’s 98,000 men having reported a single word about such an event in 312. The puzzle is compounded by another early account by Lactantius, a Christian scholar and teacher of Constantine’s son Crispus. In On the Deaths of the Persecutors 44.5–6 (ca. 313–315), Lactantius says that Constantine was told in a dream (not through a vision) to inscribe his soldiers’ shields (not their standards) with the superimposed Greek letters chi and rho (not a cross). Chi and rho are the first two letters of the Greek word Christos.

A more imaginative explanation of Constantine’s experience may be found in the journal Byzantion, in an article titled “Ambiguitas Constantiniana: The Caeleste Signum Dei of Constantine the Great.” The writers contend that the emperor looked up at the night sky (not during the day) and saw a conjunction of Mars, Saturn, Jupiter and Venus in the constellations Capricorn and Sagittarius (Michael DiMaio, Jörn Zeuge and Natalia Zotov, 1988). This would have been viewed as a bad omen by his mostly pagan soldiers, but Constantine was able to manufacture a positive meaning by explaining that the conjunction was in the form of the Chi-Rho and was therefore a favorable sign.

But there is another account of a vision that may indicate a conflation of stories and claims and at the same time resolve the contradictions between accounts. An anonymous pagan orator, eulogizing the emperor in 310, speaks of a religious experience at a pagan temple in Gaul that year, when Constantine claimed to have seen a vision of the sun god Apollo. Though not all scholars agree, it seems likely that this was the origin of the well-known Christian account of the vision. According to some of them, including A.H.M. Jones, Peter Weiss and Timothy Barnes, what Constantine and his army actually saw in 310 was a solar halo phenomenon—the result of the sun shining through ice crystals in the atmosphere. Later, the emperor, preferring to ascribe victory to his Christian Savior’s intervention, reinterpreted the experience.

The emperor’s view of religion in general was typical of his time. As James Carroll writes, it was a “fluid religious self-understanding.”

That the emperor should at the same time be linked to Apollo comes as no surprise, however, since so many Roman emperors before him worshiped the sun. And there are many indications that Constantine continued to honor the gods of his fathers throughout his life. The emperor’s view of religion in general was typical of his time. As James Carroll writes, it was a “fluid religious self-understanding” (Constantine’s Sword, 2001). Divine favor meant success, so it was incumbent on any ruler to seek the favor of any or all of the gods. Accordingly, when the Senate dedicated Rome’s still-famous victory arch to Constantine in 315, the inscription read that he and his army had conquered Maxentius “by the inspiration of divinity and by the greatness of [his] mind.” The words were deliberately ambiguous so as not to offend anyone—man or god.

As noted, Roman Christianity had achieved the status of an approved religion in the empire almost 50 years before Constantine came to power in 306, though the emperor Diocletian (284–305) indulged once more in persecuting Christians. Constantine believed at the time that this would lead to bad fortune for the empire.

In the wake of Diocletian’s rule, the politically astute Constantine recognized the advantage of bringing together the factious empire. And the form of Christianity in which he became increasingly interested allowed him the opportunity to promote unity. Traditional pagan religions were varied in belief, and while they continued to be tolerated, they could not deliver unity in the same way that Christianity might—though on this point Constantine was to be tested as he found the new religion itself rent by division over doctrine. Accordingly, the man whose coins were inscribed rector totius orbis (“ruler over the whole world”) set limits on his tolerance. In his desire for religious unity, Constantine opposed any version of Christianity that was not orthodox by Roman Catholic standards.

Worshiping Other Gods

Soon after he captured Rome, “the Christian emperor” approved a new priesthood in Egypt, dedicated to the worship of his imperial family, the Flavians. This action was to be expected, since the imperial cult was still in vogue. And if there was not a compelling reason to change a popular custom that kept him elevated in people’s esteem, why do so? What Constantine succeeded in doing was to adapt previous traditions for new purposes. According to Jones, “the institutions devoted to the imperial cult were without difficulty secularized and continued to flourish under the Christian empire” (Constantine and the Conversion of Europe, 1978).

In a related example, the emperor retained the pagan religious title Pontifex Maximus (supreme pontiff; literally “great builder of the bridge” [between the gods and men]) throughout his life. Its practical aspect was that he continued to hold supreme authority over all religions, including, of course, his preferred version of Christianity.

This is not to say that he did not move away from pagan practice at times. For example, in 315, as the celebration of his 10th anniversary as Augustus got under way, he refused to allow sacrifices to the traditional Roman gods.

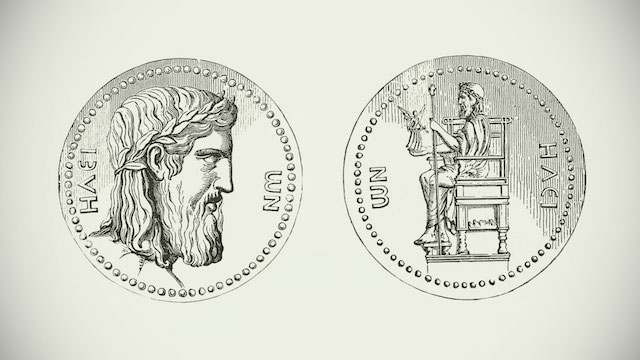

The sun nevertheless provided the emperor, like so many others before him, with a symbol of life-sustaining power, strength and heavenly light, which he could manipulate to his advantage. In 274 the emperor Aurelian had declared Sol Invictus (the Unconquered Sun) the one supreme God. It is not surprising that soon after succession to emperor in 306, Constantine, filled with overweening ambition, had coins struck with the words “To the Unconquered Sun my companion”—a practice he continued into the 320s.

In the East, meanwhile, he reestablished the ancient Greek city of Byzantium as Constantinople, or “Constantine’s City”—his new capital. The revitalized city was styled on Rome and completed in 330.

Relics Old and New

The fusion of pagan and Christian elements continued to be a mark of the emperor’s approach to religion. Syncretism was apparent in many of his activities, from architecture to Christian practice. In his new hippodrome, he installed a serpentine column from the Greek cult center of Delphi, where it had stood in the Temple of Apollo since 479 B.C.E. Nearby was the First Milestone, from which all distances were measured, making the city the new center of the world. Above the milestone was positioned a relic from the Holy Land, “discovered” by Constantine’s pilgrim mother, Helena. It was believed to be nothing less than the “True Cross” of Jesus’ crucifixion.

The emperor also erected another structure, the remnants of which are still located in Istanbul (the modern name for Constantinople) and known as the Burnt Column or the Column of Constantine. One hundred feet high and made of porphyry, it stood on a 20-foot plinth containing the Palladium—a pagan trophy—and supposed relics with biblical origins: Noah’s hatchet, Mary Magdalene’s ointment jar, and what remained of the baskets and bread from Christ’s miraculous feeding of the people, were all said to be kept there beside a statue of the goddess Athena, brought from Troy by the Greek hero Aeneas. The column itself came from the ancient Egyptian sun-cult center, Heliopolis (City of the Sun).

Atop the column was a statue whose body was taken from Phidias’s statue of Helios, the young Greek god of the sun. The head was crowned by a typical radiate diadem, with features fashioned to resemble Constantine’s own. Historian John Julius Norwich writes that in the Column of Constantine, “Apollo, Sol Invictus and Jesus Christ all seem subordinated to a new supreme being—the Emperor Constantine.”

When the emperor established a permanent day of rest empirewide in 321, he was no doubt happy to choose a day that had significance for Roman Christianity and that happened to coincide with his devotion to Apollo. Accordingly he wrote, “All magistrates, city dwellers and artisans are to rest on the venerable day of the Sun.” Nowhere did he mention Christ or “the Lord’s day.” He only mentions veneration of the sun. Jones notes that it seems the emperor “imagined that Christian observance of the first day . . . was a tribute to the unconquered sun.”

When Constantine established the date for the celebration of Easter, he formalized the method still used today: Easter Sunday is the first Sunday following the first full moon after the vernal equinox, when the sun’s position marks the beginning of spring. This was the practice of the churches at Alexandria in Egypt and in the West when Constantine came on the scene, whereas the churches in the East established the date based on the Jewish Passover. While the sun’s position was part of the new method of calculation, it was probably Constantine’s hatred of the Jews rather than his devotion to Apollo that caused him to insist on the change. As he wrote in a summary letter, “Let there be nothing in common between you and the detestable mob of Jews! . . . with that nation of parricides and Lord-killers” (Eusebius, Life of Constantine 3.18.2; 3.19.1).

No doubt, in the case of the other main celebration in Christianity—the date of Christ’s birth, which had been earlier made to coincide with the pagan observance of the winter solstice and the birth of the sun god in late December—Constantine was more than pleased.

Constantine the Convert

Constantine’s actual conversion to Christianity did not occur until he was dying, for only then did he receive a rite of baptism. Though it is often claimed that it was usual for people of the time to put off such commitment until their later years, Constantine’s everyday way of life never corresponded to that of Jesus, Paul and the early apostles, whom he claimed to follow. His involvement in the executions of his wife, Fausta; his son, Crispus; and his sister’s stepson, Licinianus, a year after the ecclesiastical conference of Nicea leave little doubt that his value system was anything but that of a follower of Christ. Certainly, aspects of Christian belief influenced his rule, but his career demonstrates more evidence of continued pagan adherence than personal Christian commitment.

Norwich notes that by the end of his life the emperor was probably succumbing to religious megalomania: “From being God’s chosen instrument it was but a short step to being God himself, that summus deus in whom all other Gods and other religions were subsumed.”

“From being God’s chosen instrument it was but a short step to being God himself, that summus deus in whom all other Gods and other religions were subsumed.”

Perhaps that is why Constantine’s lifelong balancing act between paganism and Roman Christianity continued in the recognition others afforded him posthumously. The Roman Senate deified him, naming him divus like so many preceding emperors and issuing coins with his deified image. According to historian Michael Grant, it was “a curious indication that his adoption of the Christian faith did not prevent this pagan custom from being retained” (The Emperor Constantine, 1993). Nevertheless, his service to his preferred version of Christianity caused the Orthodox Church to name him a saint.

As for Constantine himself, he made sure that he would be remembered in a very specific way. For several years he had taken to referring to himself as “Equal of the Apostles.” Thus he planned to be buried in a church erected in Constantinople during his reign: the Church of the Holy Apostles. There, upon his death in the summer of 337, the emperor was placed in a sarcophagus and flanked on either side by six standing sarcophagi said to contain relics of the 12 apostles. He was the 13th apostle, or better yet, cast in the role of Christ Himself in the center of his original disciples. He was Constantine the Great, an emperor whose pretensions at godhead suppressed his Master’s commanded humility, even in death.

READ NEXT

(PART 3)