X-Risks and Human Destiny

In the face of threats to our continued ability to exist on the earth, Britain’s Astronomer Royal discusses not only the risks but also some of the alternatives that scientists are currently exploring.

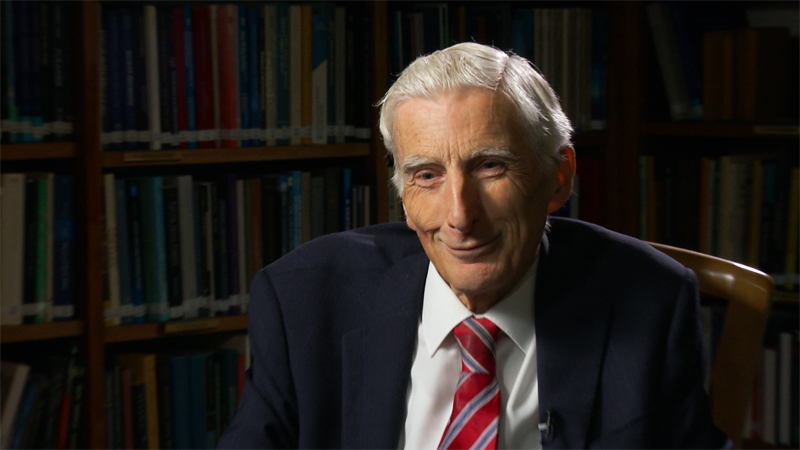

At Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER), Martin Rees and his colleagues are concerned with the multiple risks that could lead to human extinction. Rees is a member of the House of Lords in the United Kingdom and also holds the title of Astronomer Royal. In this June 2017 interview, Vision publisher David Hulme asked him about his concerns—and his hopes—for the future of our species.

DH The study of X-risks, the factors that may contribute to humanity’s near or total extinction, has become quite a preoccupation for you. You’ve written about it before. Many of these risks have always been present—volcanoes and earthquakes, for example; others, such as pollution and nuclear weapons, are relatively new. Why was it only in 2012 that you and your colleagues formed the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk?

MR Two things have changed over recent decades. First, the main threats that concern us no longer come from nature—from asteroids, earthquakes, etc. They are caused by human actions. We’ve entered a new era, the Anthropocene, where the future of our planet depends more on what we do collectively and individually than on nature itself. The first manifestation of this was probably the nuclear age when, during the Cold War, we could have stumbled (by miscalculation or design) into a real Armageddon with tens of thousands of nuclear weapons going off. So we are now in a situation where we are threatened by the downsides of our own technologies.

Another thing that’s changed: we are in a global, interconnected world, so it’s unlikely that a major part of the world could suffer devastation without it impacting on the rest of the world. It’s not like in earlier centuries when there could have been a localized disaster in one region which completely unaffected the rest of the world. We are more interconnected and more vulnerable.

DH Francis Bacon wrote New Atlantis, describing a scientific utopia. I wonder what he would make of the Anthropocene. Has science failed in that regard?

MR I certainly wouldn’t say science has failed. I think the lives we all live are far better than those lived by any previous generation, and we certainly couldn’t provide any kind of life for the 7.3 billion people now on this planet without the advances of technology. But we need to be mindful that there are also downsides. The stakes are getting higher. The challenge for the coming decades is to harness the benefits of the exciting new developments—in particular biotech and artificial intelligence—and avoid the downsides.

DH How do you see artificial intelligence (AI) contributing to a better future?

MR We’ve benefited hugely from information technology. The fact that someone in the middle of Africa has access to the world’s information, and we are all in contact with each other—it’s a wonderful thing. But if you look further ahead, we wonder whether AI will achieve anything approaching human intelligence, and that raises another set of questions. Machines and robots are taking over more and more segments of the labor market. It’s not just factory work; routine accountancy, medical diagnostics and surgery, and legal work will be taken over. Ironically, some of the hardest jobs to automate are things like plumbing and gardening. In order to provide a decent society in the light of these developments, we’ve got to have massive redistribution of wealth so that the money—as it were, earned by the robots—is used to fund huge numbers of dignified, well-paid, secure posts for carers for young and old, people in public-sector jobs of that kind.

DH Biologist E.O. Wilson has said we are tearing down the biosphere and that it’s going to be forever if we don’t do something rather urgently. Is the collapse of the biosphere the most critical risk you see?

MR I think it’s something we have a special responsibility for, because as E.O. Wilson himself said, if human actions lead to mass extinctions, it’s the sin that future generations will least forgive us for, because it will be an irreversible loss of biodiversity. It’s an ethical question: How much do you care about that? Many environmentalists think the natural world has value over and above what it means for us humans, but it does mean a lot for us. If fish stocks dwindle to extinction or if we cut down the rain forests, we may lose benefits to humans. But it’s more than that. We should surely regard the preservation of our diversity as an ethical imperative in its own right.

“If human actions lead to mass extinctions, it’s the sin that future generations will least forgive us for, because it will be an irreversible loss of biodiversity.”

DH You’ve said that we have a 50-50 chance of making it to the end of the century. What’s the basis for that calculation?

MR Well, we can’t really calculate it, but I would certainly say that we have at least a 50 percent risk of experiencing a very severe setback to our civilization between now and the end of the 21st century due to the collective pressures of 9 or 10 billion people on the planet or, more likely, disruption stemming from the misuse of these ever more powerful technologies by small groups, by error or by design.

DH Yet it sounds to me, in your writings, that you’re in fact optimistic.

MR I’m a technical optimist but a political pessimist in that I think the advances of technology and science are hugely beneficial; we won’t get through the century by not using them. We’ve got to develop these technologies, but we’ve got to realize that as they get more powerful they have bigger downsides. In particular, they enable small groups of people, even individuals, to have a global impact. As I like to say, the global village will have its village idiots, and their idiocies will have global range. It’s going to be a new challenge to governments to ensure that we can balance the tension between privacy, security and liberty when a few people can cause such catastrophic global damage, added to the risks caused by our collective impact on the planet.

DH One author who’s also written about existential risks includes self-delusion as a serious problem. In the face of existential risks, we allow ourselves to believe that science will always solve it, so “I don’t need to worry about it.” Are we deluding ourselves in that respect?

MR It’s certainly true that we are in denial about things that ought to concern us, especially these risks which could be so catastrophic that one occurrence is too many. There’s also a feeling of helplessness on the part of individuals. They don’t know what they can do. And that’s why I think it’s very important that we should bang on to our politicians about this. It’s hard for politicians to focus on long-term global issues in the pressure of short-term concerns. Politicians are influenced by what’s in the press and what’s in their inbox. So as scientists we have a responsibility to ensure that the best scientific ideas are fed into the political process.

Sir Martin Rees, cofounder of the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk

DH When it comes to solutions to X-risks, you and your colleagues have focused on bringing together the best of physics, computer science and philosophy. I was interested that philosophy was part of it; the hard and applied sciences don’t usually go there.

MR I think we obviously need social science and humanistic understanding as well as the physical sciences. To give a simple example: Everyone in even a megacity in the developing world has a mobile phone. Does that make a potential pandemic even worse or does it make it better? Mobile phones can spread panic and rumor. They can also spread good advice. Social science needs to be used to see how we can minimize the effect of some disaster. Another issue that concerns me very much: if there were a natural pandemic, I worry that even if the casualty rate was only one in a thousand, that could lead to social breakdown because we’d have overwhelmed hospitals. In the Middle Ages everyone was fatalistic; a third of the population died, the rest went on as before. Once the capacity of hospitals is overwhelmed, certainly in the United States, I fear there could be severe social breakdown. And that’s a social sciences issue.

DH H.G. Wells said there’s no way back into the past. It’s the universe or nothing; that’s the choice. Do you agree with that? How do we get past the existential bottleneck you’ve raised?

“I don’t have any solutions. I do think we’re to have a bumpy ride through this century.”

MR I don’t have any solutions. I do think we’re to have a bumpy ride through this century. Some people say that maybe H.G. Wells was thinking we can go and have new colonies in space. I’ve thought quite a lot about the long-term future of the human species, and I think we’re going to be able to modify human beings by cyborg and gene-editing techniques and in effect redesign human beings. I think we’re going to try to regulate all these technologies on grounds of prudence and ethics, but we’ll be ineffective in regulating them, because whatever can be done will be done somewhere by someone. It’s not like 40 years ago when the first scientists to do recombinant DNA met to decide guidelines. They agreed on a moratorium and observed it, but now the enterprise is global, with strong commercial pressures, and to actually control the use of these new technologies is, I think, as hopeless as global control of the drug laws or the tax laws. So I am very pessimistic about that.

Some people talk about humans spreading beyond the earth to Mars or elsewhere. I’m not a great fan of manned space flight, because the practical case is getting weaker as the robots get better. In the hostile environment of space, robotic fabricators and explorers are going to be the way we actually build things and explore. If people go into space, it will only be as an adventure—in the same way as people go to the South Pole or climb Everest. It’s a dangerous delusion to think that there’ll ever be a community on Mars escaping from the earth’s problems. There’s no Planet B, as it were. But there will, I think by the end of the century, be a small community of eccentric pioneers living (probably) on Mars. They will be away from any regulations we impose on Earth regarding cyborgs and biotechnics. Moreover, they’ll have every possible incentive to adapt their progeny to this very hostile environment, which humans aren’t at all adapted to.

DH Will they take their human nature with them, I wonder?

MR Well, human nature is clearly very malleable; it’s hard for us to understand the attitudes and concerns of earlier generations. So human nature may indeed change. Let’s hope it changes in a way that allows a cooperative society to develop. In the very long run, of course, if we read our science fiction, we realize that perhaps what we will have is not a civilization but some single, huge mind. Even H.G. Wells thought about that.

DH After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Einstein famously said “it is easier to denature plutonium than it is to denature the evil spirit of man.” What do we do to change the existential risks associated with human nature?

MR I think it’s very hard. We obviously have concerns that stem from religious extremism in particular at the moment. One can hope that that will eventually be eroded. It’s also incumbent on politicians to foster a society that minimizes opportunities and occasions for legitimate grievance. Obviously a disaffected minority is going to be in a more empowered position in future because of advanced technology. So there’s an even stronger incentive to have the kind of fair and more equal society that many of us want anyway—because otherwise there’ll be a much greater chance of severe disruptions.

DH The anthropic principle says the universe was made with humans in mind. Now you’re addressing the pros and cons of the Anthropocene, the age when humanity is the dominant influence. What’s the relationship between the two, if there is one?

MR A question which we astronomers ask is whether there is life—even life like us—elsewhere, because we’ve made the important discovery, mainly in the last 10 years, that most of the stars we see in the sky are orbited by retinues of planets, just like the sun is orbited by the earth and the other familiar planets. This makes the universe far more interesting and raises the question of how important life is in the universe. Within 10 years we will have good enough observations of some of the earth-like planets orbiting other stars to have some idea whether they have biospheres. We will learn about how widespread some kind of life is in the universe, I think within 10 or 20 years. And that raises a separate question: Is there any intelligent or advanced life, because there’s a big difference between saying there’s some sort of biosphere and saying there’s some sort of intelligent technological life. It would be a huge discovery if we could detect something artificial, which would indicate that concepts of logic and physics weren’t unique to the wet hardware in human skulls.

We are in this enormous universe where there are a hundred billion galaxies, each with a hundred billion stars, and many of those stars will have Earthlike planets around them. We understand that this huge domain is governed by basic laws of physics and also by laws which seem to be the same everywhere we can observe. If we take the spectrum of light from a distant galaxy, we can infer that the atoms in it are just like the atoms here on earth. The force of gravity is the same. But this has led to another development, which might be another Copernican Revolution, because there’s no reason to think that the observable universe, vast though it is, is the entirety of physical reality. And so there’s a possibility that there’s a lot more space beyond what we can see. Even though the laws of physics are universal within the region we can observe, if that vast region is only a tiny part of physical reality, then it remains open to envisage that different parts of this grander physical reality are governed by different physical laws. We don’t know at all. But I would hope that in 50 years’ time we might be able to address questions like “Does physical reality involve just one big bang or many?” and “Does it involve domains where the physical laws are different from what they are here?”

DH In a recent article I read, one of your CSER cofounders, Jaan Tallinn, seemed a bit dismissive when he said that philosophers go on talking nonsense and that mathematical models are necessary to reduce their intuitions to what is testable. Is there a place at CSER for the great philosophical and/or religious traditions?

MR I think there is. One issue is the extent to which we should take into account the right of future generations and those as yet unborn. This is a big philosophical issue. [British moral philosopher] Derek Parfit wrote famous papers on this, as did others. The extent to which you take into account the welfare of people as yet unborn is obviously an ethical question.

Another question comes up in the context of AI, which is the extent to which, if we do have machines that achieve more and more human capabilities (which I think we surely will do; bear in mind we’ve had machines that can do arithmetic better than us for 40 years), will we regard them as zombies, or will they be conscious? There’s also a big philosophical question about whether consciousness is an emergent property beyond a certain level of complexity or whether it is something special to the particular kind of wet hardware that we, apes and dogs have. It’s a very important question on the interface of computer science and philosophy. To put it slightly trivially, if we have a robot that seems rather humanoid, then do we have to worry about whether it’s unemployed or bored?—because we do worry about human beings not being able to fulfill their potentialities. Even some animal species, we feel, need to be able to live in a natural way. So are we going to start feeling that way about these machines? That’s an ethical and philosophical question.

DH Is there an evolutionary selective pressure that can push humans away from the kind of sabotage of civilization that you’ve talked about?

“Darwinian selection doesn’t apply to human beings now. We keep people alive, and any selection is artificial and by design, as it were.”

MR Well, one important point is that Darwinian selection doesn’t apply to human beings now. We keep people alive, and any selection is artificial and by design, as it were. In future it will be possible, through genetic modification, to change people’s physique and personality, so that’s going to be a big issue. What sort of people do we want to have? Do we want to allow these techniques at all? And should it be allowed to an elite if it’s not available to everyone? My gut feeling is that we should try to constrain and regulate this on Earth, but if there are a few crazy people on Mars, then wish them good luck in developing into a new species.

DH Thinking about the macro and the micro aspects of our existence, the extent of the universe, and the latest findings from the Large Hadron Collider—what we can now comprehend is amazing.

MR But of course, the big thing we don’t yet have is the theory that unifies the very large and very small; and to understand the nature of space itself, we need that. To test such a theory will only be indirect because it’ll have to depend on calculating consequences which are in the observable world or in the experimental range, and unless we have consequences that we can validate, we will never take these theories seriously. At the moment there are lots of theories, but none of them have been battle-tested in that way. I think everyone agrees that the key scale is very tiny. Until we have a theory that deals with that scale, we won’t understand the very early stages of the big bang, and we won’t understand the nature of space itself at the deepest level.

DH Is that why Einstein called it spooky?

MR Well, he thought all quantum theory was spooky. The point is that we shouldn’t be surprised it’s spooky. I would say it’s rather remarkable that we actually have made as much progress as we have in understanding something about the quantum world (to the extent that our technology is based on it) and something about the cosmos, but I think we have to bear in mind that there may be some deeper levels of reality which our brains can’t grasp any more than a monkey can grasp quantum theory.